This is part 3 of my series on the music of the year 1980, when I was ten years old, inspired by The Album Years, a podcast by Steven Wilson and Tim Bowness. You can find part 1 here, and part 2 here, and you can find The Album Years episode on 1980 on your favorite podcast app.

This series is an exercise in non-nostalgia. It is not a teary-eyed trip back to my ten-year-old self. After all, I didn't much like being ten years old. People generally don't take kids seriously, and I was very much aware of this. Furthermore, most of the music that we are exploring here was not what I was listening to in 1980.

As much as I love music, my relationship to it is essentially non-nostalgic. Sure, there is some music that I associate with a particular time and place—often to the music's disadvantage. For example, I will always associate the Smiths with drunken idiots in my freshman dormitory who listened to them at high volume in the wee hours of the morning. To this day, Morissey's whiny voice brings up buried feelings of rage and a desire to sleep—this despite the fact that I am of the precise demographic that should love The Smiths (white, male, pseudo-intellectual, born in 1969).

Often some of the music that I loved three or four decades ago does not hold up when I dust it off in 2024, and some of the music that I ignored at the time I can't get enough of now. This is because the personal canon is always a work in progress if we listen and read critically and with attention. We are not the same people in our fifties that we were at ten or twenty or thirty—thankfully. The process of personal canon formation requires us to be open-minded and open-eared, to be curious about the new (and the old), and to reject the algorithm as taste-maker.

Of the four albums under consideration today, there is only one that I was at all familiar with in the 1980s, and it is now probably my least favorite of the bunch, though I still like it. Let's start with the best, and the one that I discovered most recently.

Kate Bush: Never for Ever

The first time I recall hearing Kate Bush was listening to the album The Sensual World in college, circa 1990, in the car of a girlfriend who was much cooler than I was. While I liked her voice and the production at the time, it was about a quarter century before I began to listen to her music in earnest. I had missed out for far too long on one of the great artists of our time. She’s amazing.

Never for Ever was Kate's third studio album and is, to my mind, a masterpiece, all the more astonishing considering that she was 22 at the time it dropped. The songwriting is remarkably mature, and the performances are poised and sophisticated. It starts with "Babooshka," one of her most memorable songs, which tells the tale of a woman who seduces her husband by writing him anonymous letters.

The influences are literate and are far more aesthetically progressive than I would have been at 22: the music of Frederick Delius, the films of Truffaut, and the novels of Henry James. The performances are often theatrical, sometimes recalling the aesthetics of film music and broadway musicals, with Kate expertly playing various roles—for example, an aggrieved newlywed who kills her new husband in "The Wedding List":

There's gas in your barrel, and I'm flooded with doom,

You've made a wake of our honeymoon, and I'm coming for you.All of the headlines said, "Passion Crime,"

Newly-weds, groom shot dead, mystery man, God help the bride,

She's a widow, all in red with his red still wet (she said):I'll put him on the wedding list,

I'll get him and I will not miss.

In "Violin," she sounds as if she is possessed by the demonic spirit at the command of the instrument. The album's closer, "Breathing," features a distant voice describing a nuclear explosion, as Kate sings: "What are we going to do without? / Oh, let me breathe."

There is not a weak track on the record. It deserves your attention.

Prince: Dirty Mind

Just as precocious as Kate Bush—born less than two months earlier than his English contemporary, in June 1958—was Prince, who also released his third studio album in 1980. This was another album that I never heard in the 1980s, a fact which may surprise some long-time readers of PCF who are aware of my longstanding devotion to Prince.

Allow me to digress for a moment and explain this apparent contradiction to the music-streaming generation. Yes, I loved Prince in the 1980s. But I also loved the Beatles, Bowie, The Police, and too many others to count. But unless a friend had the record for me to borrow (and to pirate on cassette), it would cost me precious dollars to buy a new album, so I had to pick and choose how to spend my very limited funds. Since Dirty Mind pre-dated Prince's emergence on pop radio, I never had a chance to hear any of it. There was no Spotify or Apple Music to satisfy my curiosity.

This was the album that made Prince a critical darling and paved the way for the artistic and commercial heights of 1999, Purple Rain, and beyond. However, I must admit that when I read critics who claim this to be among his best albums, I have no idea what they are talking about. Yes, it is fresh and fun and provocative. Prince has incorporated the sounds of New Wave into the funk and soul style of his first two albums, and there are some great tunes (the title track, "When You Were Mine," "Uptown"). But off the top of my head, I can think of ten Prince albums that I prefer to this one. It shows great promise of much of the magnificent music that was to come, but it is not close to the artistic achievement of his best work.

Tangerine Dream: Tangram

By 1980, Tangerine Dream had already released twelve albums and had, along with their German compatriots Kraftwerk and Can, become tremendously influential for the emerging world of electronic music and what would eventually come to be called “ambient music” (Brian Eno's coinage).

Until a few years ago, the only thing I knew about Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream was that David Bowie was listening to them around the time of his "Berlin Trilogy" of albums in the late 70s. Then one day, a friend, who was (like the college girlfriend who introduced me to Kate Bush) much cooler than I was, invited me over to his house with the expressed intention of introducing me to "Krautrock," the German electronic and experimental rock music of the 1970s. He had many shelves of vinyl, including some original pressings of Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream. That day opened up a whole realm of music for me.

Tangerine Dream created vast soundscapes in the pre-digital era from analogue synthesizers and sequencers. Tangram is in a sense a sort of synthesis of much of their work from the 1970s, before they began to change and evolve their style into more short-form pieces in the 1980s and beyond. It is immersive, strange, and sometimes beautiful. It can send you into a sort of trance state, though it is, to me, much more musically interesting that what is called "trance music" these days.

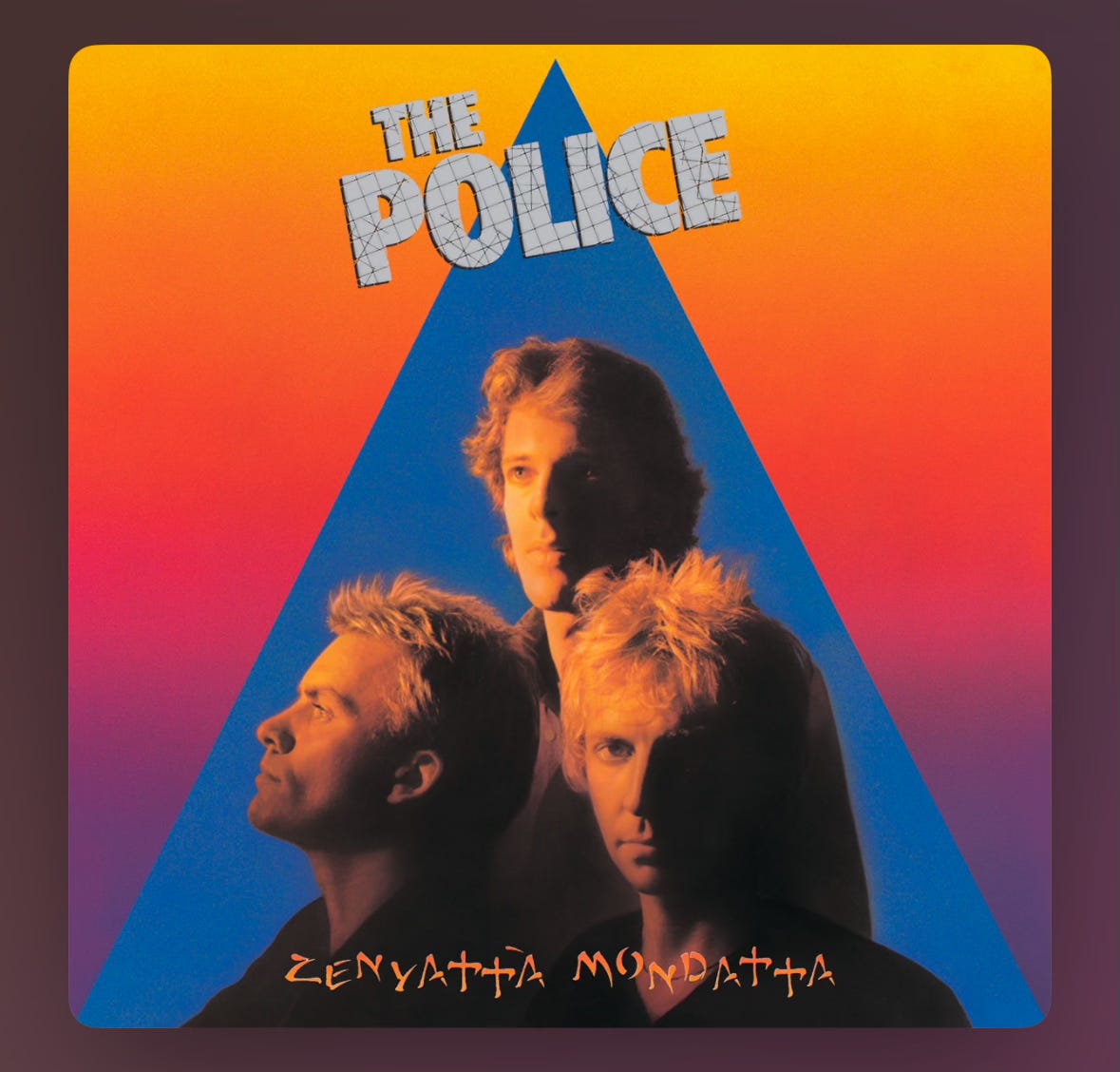

The Police: Zenyatta Mondatta

I bought this record on vinyl some time in the early 80s, probably in the wake of Synchronicity craze. Of the five studio albums of The Police, this is probably the weakest, though I still love it. There is some filler. (You may safely skip "Bombs Away" and "Behind My Camel.") But there are also some gems in addition to the two classic singles "Don't Stand So Close to Me" and "De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da." "Driven to Tears" is a clear-eyed consideration of our responsibility as individuals to address the world's suffering, and "When the World Is Running Down" takes that question to its cynical extreme, as it imagines life as the last remaining human, living on canned food and watching the same video tapes over and over. (How does he have electricity?) And “Canary in a Coal Mine” is irresistible.

The album also features the dreamy and druggy “Shadows in the Rain,” a much better, ferociously jazzed up version of which appears on Sting’s first solo album, The Dream of the Blue Turtles. On that album, Sting would dramatically depart from the sound of The Police, employing jazz greats Branford Marsalis (saxophone) and Kenny Kirkland (keyboards), both of whom tear it up in this remake. As the drums begin the track, you can hear a frantic Branford shout: “Wait! Wait! What key is this in?” No one answers him, but he does just fine.

But that would be four years in the future. In this version, Sting really does sound like he woke up in his clothes:

Woke up in my clothes again this morning,

Don't know exactly where I am,

And I should heed my doctor's warning,

He does the best with me he can.

We’ve all been there.

Finally, in response to Zenyatta Mondatta, I can say that I am forever thankful that it introduced me to Nabokov. If you know, you know.

----

I hope all of you had a restful and happy Thanksgiving, despite the fact that it seems like “the world is running down." More Gulliver and more 1980 to come soon.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet eight-track player to yours.

StIng, Sting, Sting!

I will stand by The Kick Inside being the seminal KB album and that Regatta de Blanc has more winners than duds. But it’s all so very subjective :)