Dear reader,

I first published a version of this piece on July 16th, 2023, when I had exactly seventeen subscribers. I thought that this would be a good time to pull it out of the archives and dust it off, in conjunction with the Bowie playlists that I featured this week. I think that Young Americans is an underrated album, at least in comparison to his more highly acclaimed records of the 70s. Here I make the case. Part two will appear on Sunday.

Yours,

John

In 1974, David Bowie recorded an album called The Gouster, a slick proto-disco record, which led off with “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)” and closed with “Right.” Late in the process, however, he radically revised the album, adding some tracks (“Fame,” most notably) and cutting others (like “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)”). The result was Young Americans, which was less slick and more soulful than The Gouster. While The Gouster, which remained unreleased until 2016, is a compelling listen, Bowie made the right choice to release Young Americans instead.

Over the next two posts, we will take a close look at Young Americans, track by track, and we will, I think, find a thematic and musical coherence as robust and interesting as those of his more overtly conceptual records, like Ziggy and Diamond Dogs. We’ll look at side one today and side two with Sunday’s post.

Title Track: “Young Americans”

The title track announces itself with an exuberant drum break and sax solo, before Bowie’s vocal enters. It is a sexier and more chesty voice than we hear on his albums from the early 70s, though there were hints of this new persona on 1974’s Diamond Dogs.

Despite this sexy voice, the initial sexual act that the song narrates is undertaken with self-doubt and is, ultimately, unsatisfying: “Took him minutes, took her nowhere” But it also signals a grasping desperation: “Heaven knows, she’d have taken anything.” The “she” here will put up with unfulfilling sex and mediocrity in exchange for some kind of stability; her lover, the “he” in this scenario, is not satisfied with this kind of life: “Her breadwinner begs off the bathroom floor / ‘We live for just these twenty years / Do we have to die for the fifty more?’” But what does he want? “All night—he wants the Young American [sic.]’”

Who are the young Americans of the title? They are the objects of desire, but also they are desiring subjects. And this introduces the major theme of the album: how to reconcile material desire (and the achievement of it) with the search for more significant meaning? The desires for material things, fame, and sex are often mistaken for something deeper, as we see in several of the album’s songs—but it always seems to disappoint. We end up feeling hollow, unable to feel: “Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?”

The America depicted by the album offers all of these tangible things (luxuries, sex, fame) but disappoints and leaves us cold. The list of things that people have “got” in the title track’s breathless lyrics is undercut by the nihilistic (and inaccurate) Beatles reference that follows it—“I heard the news today, oh boy.” This bit of realism is provided by the backing singers, interrupting the lead vocal’s reverie. (The backing singers are important throughout the album; they act as Greek chorus, sirens, moral voices, and foils in turn.) But even that list of possessions is undercut by consequences (“Mamma’s got cramps, and look at your hand shake”) as well as potential ironies (“Black’s got respect, white’s got his Soul Train”).

Despite the self-awareness of white, “plastic soul,” it is the music of America that offers the closest thing to higher meaning, particularly in the record’s most gospel-inflected moments, which sound completely unironic, even if they are not always convincing. The search for that one song that can “make me break down and cry” announced by the title track becomes the desperate search of the album.

Where can I find something to move me in a world of desperate, conspicuous consumption?

It must be American music that saves us, because the other aspects of American life that the song recites simply distract from the harsh political and social realities of the mid-70s: American forgetfulness as a defense mechanism: “Do you remember your President Nixon? / Do you remember the bills you have to pay / Or even yesterday?” (Nixon had resigned shortly before Bowie recorded this track—memory as short then as it is now.)

As if in response to these sobering questions, the song builds to gospel ecstasy, with the lead vocal’s verbal outpourings, the backing vocals sounding more and more like a gospel choir, and David Sanborn’s saxophone (whose presence may be the album’s most distinctive instrumental marker) weaving its improvisations, as if participating in early jazz polyphony, updated for the 70s. Indeed, the song seems to participate in the African-American tradition of musical ecstasy in response to suffering—as in the departure from the grave site at a jazz funeral.

In the course of the song, the singer seems to move through a number of American personas, all searching for significance and all failing to find it, to the point that he asks if you would “carry a razor . . . in case of depression,” this in spite of the relentlessly celebratory tone of the music—a mask of happiness over suffering, a common American tendency.

As the song builds towards its ecstatic climax, the singer’s persona becomes both brutal and brutalized—unable to free himself from the judgment endemic in American culture, of misogyny, of racism, of classism: “And ain't there a woman I can sock on the jaw? / And ain't there a child I can hold without judging? / Ain't there a pen that will write before they die?” Indeed, the song seems painfully aware of the racial appropriation inherent in the album’s project, but as Daniel Laforest has argued, Bowie’s awkward and stiff television appearances performing this music in 1974 and 1975 demonstrate an apparent acknowledgement that that he is posing, and this is “plastic soul,” as he himself called it.

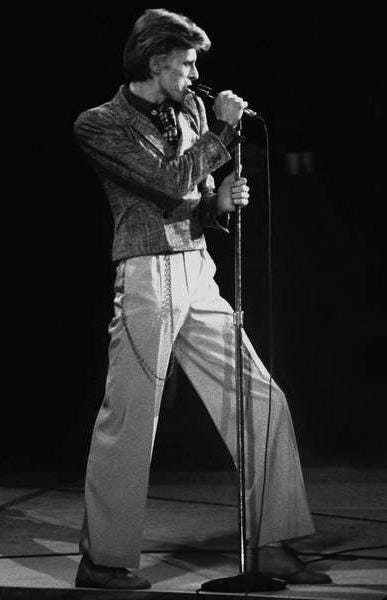

In a 1974 performance of the song on the Dick Cavett show, Bowie strums a 12-string guitar (a distinctly white instrument, associated largely with folk music and groups like The Byrds) and dances stiffly, his oversized “Gouster” suit hanging loosely on his emaciated frame, while his African-American backing singers crowd together behind him and to his left, looking far more elegant and suave than he does. The vision offered here is clear: this aspiring white boy wishes he had soul but can’t pull it off. A year or so later, with the emergence of the Thin White Duke persona on 1976’s Station to Station, this aspiration has been rejected in favor of pseudo-aristocratic coldness, even if the music retains much of the Young-Americans groove. By this point, we will be on our way to Berlin and the experiments of the late 70s.

“Win”

The musical exuberance of “Young Americans” gives way to the dreamy opening of “Win,” with its gentle guitar and multi-tracked, heavily reverbed saxophone. This tune did not make it onto The Gouster, most likely being too ethereal for that record’s proto-disco vibe. Indeed, the first verse signals a shedding, or at least a relaxing of the anxiety-driven desires narrated in the opening track: “slow down, let someone love you / I never touched you since I started to feel.” Urgent physicality here seems to work in opposition to sincere “feeling.”

In some ways, the song seems to respond to the anxious suicidal elements of the opening track (“would you carry a razor”) with the declaration, despite the fact that “somebody lied,” that “I say it’s hip / To be alive.” This statement, however, comes as the tune builds to the chorus and is followed by a discordant, high-pitched tone on the guitar that disorients the listener, just as the singer observes: “Now your smile is wearing thin / Seems you’re trying not to lose / Since I’m not supposed to grin / All you’ve got to do is win.”

The discomfort signaled by this chorus (despite the easy-going verse) is emphasized by the easy promise of the last line: a central deception of the American cultural landscape explored by the title track, and indeed of the myth of the American dream, is idea of universally available success, which can happen for anyone if they will just let it. All they have to do is win. Easy peasy. The backing singers repeat “That’s all you’ve got to do” and follow this, oddly, with “it ain’t over, no.”

What ain’t over? One possibility is that this line is another easy bromide of American life: “It ain’t over till the fat lady sings,” or Yogi Berra’s variation, “it ain’t over till it’s over,” suggesting that there is always a chance to win in a baseball game (or in life), no matter how bleak the odds. To “win,” for example, is inevitable in the narrative of sentimental sports movies, the larger the deficit to be overcome, the more “satisfying” (and predictable) the climactic win. This reading accords with the empty aphorisms of the next verse (“wear your wound with honor, make someone proud”), after which the chorus repeats twice, the second time with a more urgent lead vocal.

The smile wears thin indeed, as the singer seems disenchanted by the mellow optimism of the lyric. After the search for meaning announced by the opening track, this song suggests a false start in the search; this route is too easy to be believable. After all, the dark demons of desire are still lurking, and they burst out in the next track, the Luther Vandross composition, “Fascination.”

“Fascination”

While Bowie’s collaborations with Mick Ronson, Brian Eno, Iggy Pop, and others have received more attention, arguably one of the most significant musical meetings of the minds of his entire career occurred when he met Carlos Alomar in 1974. Alomar had played guitar with soul and jazz groups, including James Brown’s band, and as a rhythm guitarist he brought a funk sensibility that utterly transformed Bowie’s sound.

Bowie had been heading in this direction for some time; the guitar on the track “1984” from 1974’s Diamond Dogs album, which Bowie played himself, seemed to gesture towards the funk-driven playing that would dominate much of the music of the rest of the decade, and the repeated riff of “Rebel Rebel” was set to an insistent, danceable beat. Alomar, however, was a far more accomplished guitarist than Bowie and helped to define the sound of Young Americans and the next year’s Station to Station with his propulsive playing.

In addition to coming up with the signature riff for “Fame,” Bowie’s first American number-one single, he also introduced David to his friend Luther Vandross, at that time an unknown but vastly talented singer and songwriter. Luther would serve as a backing vocalist for most of Young Americans. Bowie was so impressed with Vandross that he included one of his compositions as the album’s third track, “Fascination,” for which Alomar’s guitar provides much of the funky engine.

In this song the demons of desire that manifest in a collage of American consumption in the album’s title track are internalized, indeed are practically allegorized. The phenomenon of Fascination in the song is addressed directly, as if it were a malevolent spirit. The feel-good (though perhaps ironic) promise of “Win” has given way to uncontrollable physical compulsion that acts regardless of the feelings of the other: “Every time I feel / Fascination / I just can’t stand still / I’ve got to use her.” Whether the female pronoun is a personification of fascination itself or is an anonymous woman who is the victim of his physical compulsion is unclear. But the consequences are the same either way: an act of sexual selfishness as opposed to mutual affection. The chorus underscores this tendency, as the backing vocals take on the persona of fascination itself, or at least the internal voice of desire, as they lead the way; they serve as the call to the lead vocal’s response:

Fascination (fascination)

Sure 'nuff (sure ‘nuff)

Takes a part of me (takes a part of me)

Can a heartbeat (can a heartbeat)

Live in the fever (live in the fever)

Raging inside of me? (raging inside of me?)

That fascination, at least at first, takes only “a part” of him suggests an internal battle between this compulsion and compassion (or reason or empathy). But he also questions whether it is possible for such compassion (“a heartbeat”) to be sustained in spite of such overwhelming desire (“the fever”). Sanborn’s saxophone, meanwhile, heavily compressed to the point that it sounds demonic, weaves seductive and insistent contrapuntal lines around the vocals.

In the second stanza fascination has transformed itself from an occasional compulsion into an ever-present motivation. The first line, “Your soul is calling,” could, again, be a direct address to a personified fascination, or it could even be the intensity of soul music itself as a manifestation of sexual energy. In either case, it has become addictive (“Seems that everywhere I turn / I hope you’re waiting for me”). And upon the second repeat of the chorus, the lead vocal and the backing vocals have reversed roles, with the backing vocals responding to Bowie’s call this time.

The suggestive voices inside the head have become a consciously voiced obsession. The sirens have seduced the sailor. A heartbeat cannot live in the fever. By the time he reaches the end of this chorus, the quality of the vocal has changed from a desperate anxiety to a full throated cry repeating “Fascination!”, and then once again: “I can’t help it! / I’ve got to use her!”

“Right”

The final track on side one comes as a relief after the fever dream of “Fascination,” as Alomar’s soothing, grooving guitar recalls the sound of Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” The song is more about groove and feel than any particular message, with the lyrics of the two verses sounding like a mantra of funk, dedicated to the “rightness” and inevitability of rhythm: “Taking it all the right way / Never no turning back.” The backing singers seem in accord, as they blithely support Bowie’s lead vocal—back on the straight and narrow after the tortured intensity of the previous track.

This is a glimpse of the promise of the right groove, the harmonious, elusive salvation offered by music, but the glimpse is interrupted mid-track by a funky breakdown during which the vocal lines become fragmented and the lyrics, though largely incoherent, are delivered with highly choreographed intricacy by Bowie and the backing singers. Documentary footage from the rehearsal sessions shows Bowie patiently coaching the singers as they work to master their rhythmically complicated parts, though in the final mix they sound as if they might be improvised.

What is happening here? One potential answer is convention: this kind of frenetic middle section is typical in groove-oriented soul songs from the time. (A disorienting guitar breakdown, for example, interrupts the in-the-pocket groove of the “Fire,” a 1974 classic by the Ohio Players.) However, the interruption also brings back the messiness of desire and impulse invoked by “Fascination,” with the lyrics punctuated by exclamations of “wishing!” and “gimme gimme,” before it resolves back to the blissful groove, which is all about the “right way.”

For one song at least, the groove wins out over the anxieties that bubble up to interrupt it. It’s significant that this song was meant to be the closing track of The Gouster, though with some differences (a different mix and an alternate opening vocal). The album that Young Americans eventually replaced was one in which the groove is ascendant and the funk is triumphant—with the ambivalence expressed in songs like “Who Can I Be Now?” (which does not appear on Young Americans) definitively conquered by the record’s dominant dance beat. The album Bowie chose to release, however, would close its first side with “Right” rather than the entire record. The closer for Young Americans would be much darker.

Look for part two (and side two) on Sunday, including a cameo by John Lennon!

As I was revising this, I read of the death of David Sanborn, whose melodic saxophone was absolutely essential to the Young Americans album. This piece is dedicated to his memory.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet saxophone to yours.

Thanks John, I am excited to dive into this!

The title track of the album is my favorite Bowie song of them all- he apes the cutting-edge soul music of the 1970s while still remaining uniquely himself.