Early in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Theseus, ruler of Athens, addresses his bride to be, Hippolyta, with this strange speech:

Hippolyta, I woo’d thee with my sword,

And won thy love doing thee injuries;

But I will wed thee in another key,

With pomp, with triumph, and with revelling.

This is an uncomfortable speech in the context of twenty-first-century sexual politics, but even in the pre-modern world it must have seemed strange. What is Theseus talking about? He has just returned from his conquest of the Amazonians, a nation of women, and Hippolyta was their queen. He has, therefore, fought these women with his Athenian army, has presumably slaughtered many of them, has captured their queen, and now has brought her home to marry her. Incidentally, the play’s opening scene also introduces a walk-on character, a servant called Philostrate. Readers of Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale may find this name familiar—for it is the false name that Arcite takes when he returns to Athens in disguise. (A wink and a nod from Shakespeare?)

Readers will also recognize Theseus from any number of sources, but Shakespeare has clearly read his Chaucer. In fact, he would later cowrite with John Fletcher a dramatic version of The Knight’s Tale called Two Noble Kinsmen. The opening of Chaucer’s version finds Theseus returning in triumph from his conquest of the Amazonians, their queen in tow.

Why, the modern reader may ask, would Theseus feel compelled to make such a conquest? The answer begins to reveal itself, at least in Chaucer’s version of the story, as one continues to read: Theseus is a figure of order, and specifically of patriarchal order, for whom a nation ruled by women to the exclusion of men is unnatural.

I say “Chaucer’s version of the story,” because, like Shakespeare, Chaucer was working from a source: Boccaccio’s Il Teseida, a 12-book epic of Theseus, imitating Virgil’s Aeneid. As long as The Knight’s Tale is, Chaucer radically compresses his source, as the Knight makes clear in his narration early in his tale: this tale is too long to give you in its entirety, he tells his audience, and so he will skip a bit:

But al that thing I moot as now forbere:

I have, God woot, a large feeld to ere,

And waike been the oxen in my plough;

The remenant of the tale is long ynough.

I wol nat letten eek noon of this route—

Lat every felawe telle his tale aboute,

And lat see now who shal the soper winne—

And ther I lefte I wol ayain beginne. (Lines 885-892)

This little passage tells us a great deal. First of all, it is probable that Chaucer composed a version of The Knight’s Tale before he conceived of the Canterbury project, and these lines indicate that he made some revisions in order to make it work within the frame. He refers here to the tale-telling game proposed by the Host in The General Prologue. Furthermore, he brings into focus the process of narrative compression. Boccaccio’s version takes two out of the poem’s twelve total books to narrate the war against the Amazonians. Chaucer seems relatively uninterested in Theseus’s military career and instead focuses almost entirely upon the story of the love triangle: Palamon, Arcite, Emelye.

Chaucer’s reasons for this tight narrative focus are not, I think, romantic. He is not so much interested in the erotic love story as he is in its philosophical implications, and this interest is what distinguishes his version of the tale from both Boccaccio’s and Shakespeare’s. It turns out, in fact, that what he adds to the tale is as significant as what he elides. And what he adds is Boethian philosopy.

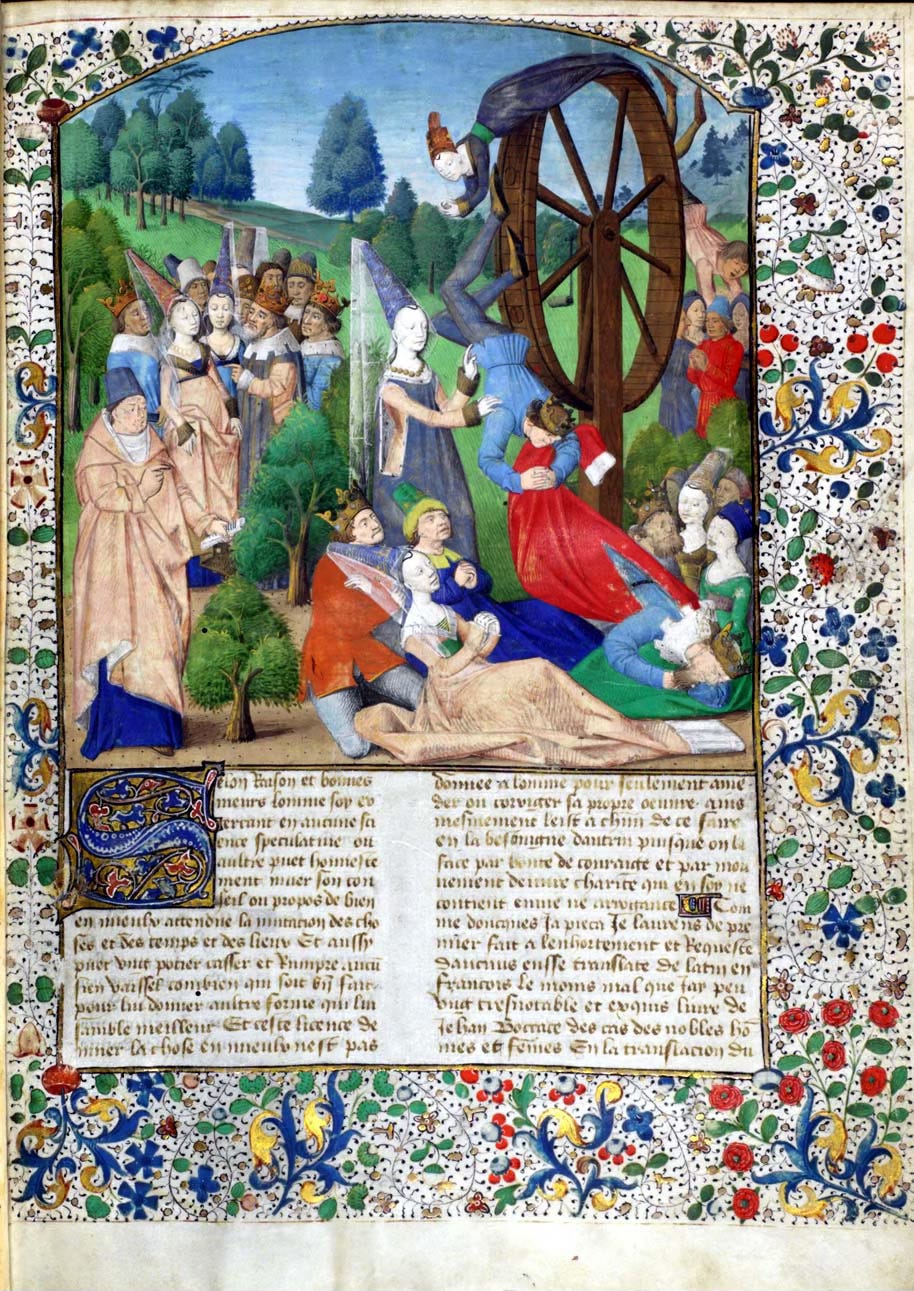

We briefly discussed Boethius, the sixth-century author of The Consolation of Philosophy, in connection to the figure of Fortune in The Book of the Duchess (see this post). Chaucer himself had translated The Consolation, and it was never far from his mind. For Boethius, the world is a sort of prison, because almost everything that occurs in it is beyond our control, regardless of how it affects us personally. This is as true for the mightiest of kings at it is for the most destitute of peasants. Fortune may favor us for a time, but Fortune’s Wheel inevitably will turn. The only reasonable response to such a world is to take it in stride and to cultivate an inner tranquility.

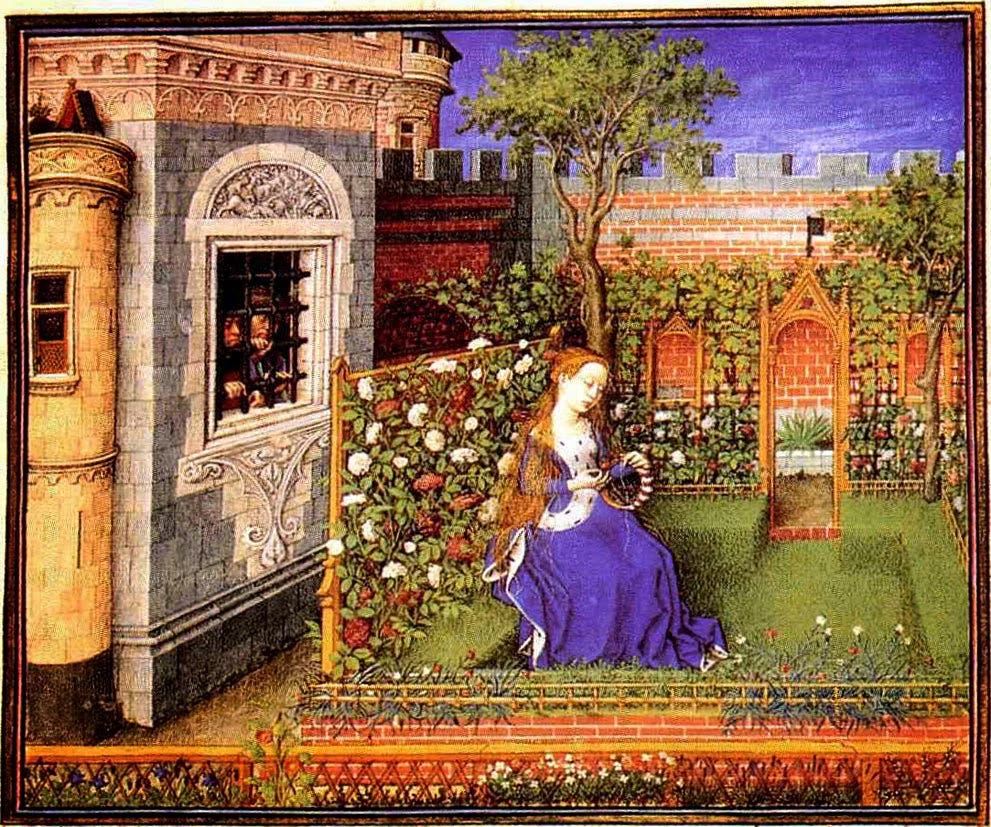

Consider, then, the hapless Palamon, who is literally in a prison, minding his own business and complaining about the fickleness of the world (always a sign of short-sightedness for Boethius), when suddenly he looks out the window of his cell and sees the beautiful Amazonian princess Emelye. He is immediately, hopelessly love-struck:

He caste his eye upon Emelya—

And therwithal he bleinte and cride “A!” (Lines 1077-1078)

Chaucer is clearly aware that this is funny (consider the ridiculous rhyme), but there is also a philosophical point here. His falling in love is, apparently, beyond Palamon’s control, as it is for Arcite who, likewise, is immediately struck when he sees her. Rather than a representation of psychological realism (which it certainly is not), we should take this as a philosophical commentary on our contingent existence.

And we come to realize in the course of the tale, that everyone in it, even the powerful Theseus, is subject to fate, to the capricious motions of the gods or the planets. Saturn, who “resolves” the dispute betwen Venus and Mars in the poem by sending a fury to kill Arcite, relishes his role as the agent of chaos in the world, in some of Chaucer’s most chilling lines:

“My deere doughter Venus,” quod Saturne,

“My cours, that hath so wide for to turne,

Hath more power than woot any man:

Myn is the drenching in the see so wan;

Myn is the prison in the derke cote;

Myn is the strangling and hanging by the throte;

The murmur and the cherles rebellinge;

The groining and the privee empoisoninge;

I do vengeance and plein correccioun

Whil I dwelle in the signe of the leoun;

Myn is the ruine of the hye halles,

The falling of the towres and of the walles

Upon the minour or the carpenter;

I slow Sampson, shaking the piler;

And mine be the maladies colde,

The derke tresons, and the castes olde;

My looking is the fader of pestilence . . . (Lines 2453-2469)

Despite Theseus’s pretensions to order, his will is transitory—as is his conquest, his kingdom, and his judgment. In response to the death of Arcite, he is helpless. His old father Egeus offers cold consolation:

This world nis but a thurghfare ful of wo,

And we been pilgrimes passing to and fro:

Deeth is an ende of every worldly sore. (Lines 2847-2849)

Death is, indeed, coming for us all, king and pauper alike, but with it comes an end to our suffering in this world. The “comic” ending of the tale, then, is shadowed by tragedy; the wedding comes in the wake of the funeral. And we question the happiness of the wedding as a wedding, when we consider Emelye’s desperate prayer to Diana that she not be required to marry anyone. Her prayer is denied. She, too, lacks agency but, rather, is subject to the whims of the gods.

So Chaucer gives a deeply philosophical spin to this tale—a far cry from the epic aspirations of Boccaccio or the playful fairies of Shakespeare. But don’t worry: things won’t remain so serious. The drunken Miller is about to burst upon the scene.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

I cannot thank you enough for this series. I teach the General Prologue and the Knight's and Miller's Tales to my seniors. This is a wonderful assist to my own efforts.

In addition to being a main character in the Knight's Tale, Theseus is also name dropped in the House of Fame. Except in the House of Fame, the dreamer makes the point that Theseus betrayed Ariadne even though she had saved his life. The Theseus in the Knight Tale's is portrayed as noble and knowledgeable, yet we begin the poem with him marrying Hippolyta after conquering the Amazons. To echo you Dr. Halbrooks, Theseus is indeed the epitome of patriarchy. But even so Theseus is subject to fate. His fame and recognition is entirely dependent on the ever-changing winds of gossip and rumor, central themes explored in the House of Fame. It puts into context his speech at the end of the Knight's Tale, that everyone including Arcite and Palamon are at the mercy of fate and no man can truly understand it, not even Theseus himself.