Bird-Bolts and Cannon-Bullets V

Mantel's final novel, Ravel's Quartet, murder in Tasmania, and salad

This is my weekly roundup of reading, listening, TV-watching, cooking, and recommendations. I’m making this week’s edition available for all readers so that those of you who are curious will get a sense of what is going on in these bonus posts for paid subscribers.

Reading

My reading this week has been almost exclusively work-related, except for my bedtime rereading of Middlemarch, which I already wrote about here. (Maybe I’ll have more to say about it after I finish, but that will be a while.) For the weeks when I don’t have new reading to tell you about, I will offer my thoughts on something I’ve read previously. This week, I offer . . .

Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light: A Reassessment

Upon its publication in 2020, right as the pandemic was on the verge of exploding, reviews of The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel’s third and final novel focusing on the life and career of Thomas Cromwell, were somewhat disappointing. (Of course, it turned out, sadly, to be Mantel’s final novel of any kind, though we didn’t know that at the time.) The first two installments had been such critical and popular darlings—both novels won the Booker Prize and were turned into acclaimed stage plays and a television adaptation with star casting—that the final book, appearing as it did a full eight years after Bring Up the Bodies, was almost sure not to fulfill the swell of anticipation that its long gestation period had encouraged.

I was among the disappointed on my first reading, the week the book came out. Though there were certainly brilliant moments, it lacked the freshness of Wolf Hall and the intense focus of Bring Up the Bodies. It was too long; it tried to do too much, to cover too much narrative material, from the aftermath of the death of Anne Boleyn, through the Jane Seymour marriage, the Pilgrimage of Grace, the birth of Edward and death of Jane, the disastrous marriage to Anne of Cleves, and, inevitably, Cromwell’s astonishingly rapid fall.

I’ve reread the book about three times since then, not because I’m a glutton for punishment, but because I’m working on a book about historical fiction, and Mantel is one of the main players. I’m now ready to revise my assessment of the novel and to suggest that it has been undervalued, largely, I think, because of the tonal departures from its predecessors and its different thematic focus.

The Mirror and the Light was a victim of bad timing: this is a novel filled with death, disease, and decline, and it also focuses on a king who is descending further into paranoia and narcissistic resentment. Appearing as it did, alongside COVID and a mafia-clown-wannabe-dictator president (and a prime minister in the UK who rivaled him both with his incompetence and his mendacity), it struck a bit too close to home. Also, Cromwell learns, as plenty have of TFG since 2016, that everyone close to the king is in danger, subject to the caprice of a monstrous ego. This did not make for comfortable, or even enjoyable reading in 2020.

Upon rereading, however, it becomes apparent that this book frames itself totally differently from its predecessors, and so the reader should not approach it expecting simply a sequel. This should not be surprising to readers of Mantel, a novelist who could never be accused of writing the same novel twice, so various and wide-ranging has been her output. While Wolf Hall was a long, immersive exploration of an historical moment and a singular consciousness, and Bring Up the Bodies was almost thriller-like in its focus on the fall of Anne Boleyn, The Mirror and the Light is a novel haunted by the ghosts of Henry’s former victims: Anne, George Rochford, Henry Norris, Catherine of Aragon, Thomas More, Bishop Fisher, the martyred gospellers, the fallen monasteries. While one might argue that some of these deserved what came to them, it was the whim of the king rather than justice that determined their respective fates. The Pilgrimage of Grace, the great uprising in the north that for a time seemed as though it might bring Henry down, is a reminder, however, that alternatives to the Tudors would not necessarily have improved things. Is social chaos to be preferred over tyranny? Will it lead to another sort of tyranny? These are the sorts of bleak questions that this book leaves us with.

But Cromwell himself is, of course, the through-line, though this is a different Cromwell from the brash, rising man of Wolf Hall or the terrifying but somehow lovable power-broker of Bring Up the Bodies. This Cromwell is not only older, he is also newly reflective, as various aspects of his past begin to catch up with him—a dead boy from his youth in Putney, his long association with the dead Cardinal Wolsey, his vivid childhood memory of watching a woman burn to death. His memory is filled with death as the shadow of his own death emerges to haunt him.

So yes, this is a book full of dying and death. It’s not for the faint-hearted. But it is very much worth reading, and perhaps rereading. I’ll be writing more about it in the future. (But I’ll be writing about Bring Up the Bodies before that!)

Related: if you missed my pieces on Wolf Hall, you can read them here, here, and here. These posts are based on the work that I have been doing for my book on historical fiction.

Here is Hilary Mantel speaking about The Mirror and the Light, and also reading from the beginning of the book:

Listening

Maurice Ravel composed only one string quartet, but it is a perfect piece of music—lyrical, lushly harmonized, dazzlingly textured, a musical world unto itself. There are many great recordings of the Quartet by the likes of Quartetto Italiano, the Julliard Quartet, the Emerson Quartet, and dozens of others. Most of the time, the artists choose to pair it on an album with Debussy, who also wrote just one quartet. It makes for a good pairing, because though both works are singular, they do share some qualities—specifically, the generous and delightful use of pizzicato in their respective second movements.

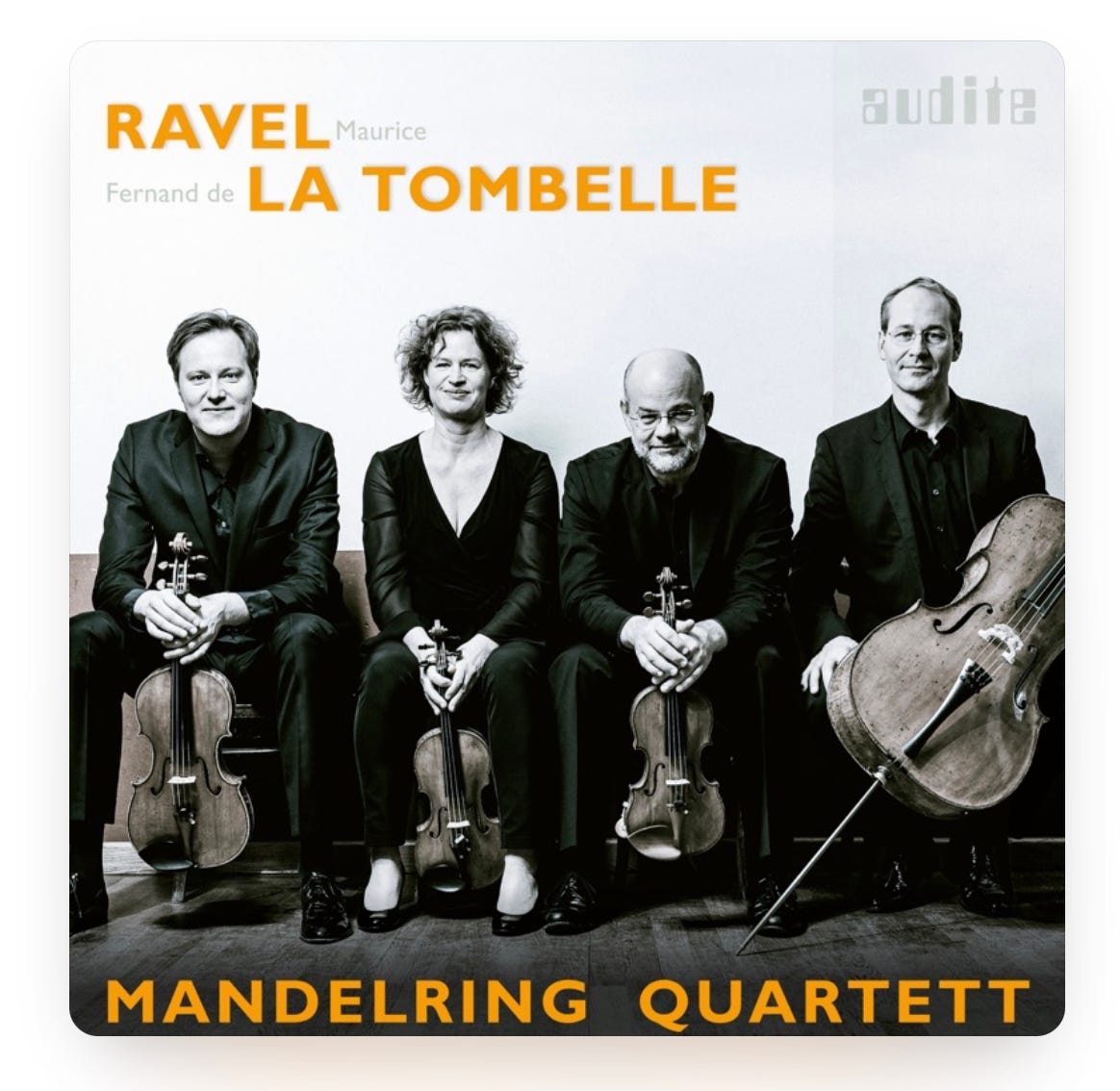

In this album by the Mandelring Quartet, however, they choose to pair it with a lesser known work by Fernand de la Tombelle. The Mandelrings, since their beginnings in Germany over twenty-five years ago, have established a reputation as an impressive group through, for example, their powerful traversal of Shostakovich's cycle of fifteen quartets. They have moved on from Shostakovich to Mendelssohn and Brahms, and to French repertoire. In 2021, they recorded both the Ravel and the Debussy quartets, but each paired with more unusual works. The Debussy recording, which is paired with two interesting quartets by Jean Rivier, is well worth your time also.

But this recording of the Ravel is phenomenal—perhaps my favorite recording of one of my favorite works. If you need convincing, go straight to the second movement, put on a good pair of headphones, and let the plucked strings dance around your brain. And the Tombelle piece absolutely holds its own against its more famous partner. It's a bit more conservative than Ravel, but it is lovely and lyrical and very French.

Here are the Mandelrings live, performing the second movement of the Ravel Quartet:

Watching

This week I began watching a show on Amazon called Deadloch. (I can't remember who recommended this, but it was on my "to watch" list.) It's a darkly funny murder mystery that takes place in a small town in Tasmania—the titular "Deadloch." The town has attracted a large and thriving lesbian community, which many of the older townspeople resent. One of the newcomers is the police chief, Dulcie, who suddenly finds herself in the midst of a murder investigation after the discovery a naked body on the beach. Her involvement with the case is much to the chagrin of her partner, Cath, with whom Dulcie has moved to the small town in order to find a better work-life balance than was possible in Sydney.

She is quickly joined by the hilariously chaotic figure of Eddie (a woman, again, much to the chagrin of Cath), a detective from the Australian mainland whom the police commissioner has assigned to the case. A large and eccentric cast of characters emerges, and much hilarity ensues, along with more deaths. At one point, Dulcie says to Eddie that "of course, Deadloch isn't perfect." Eddie responds: "It's Satan's fucking snow globe." (You must imagine this with an Australian accent.)

I'm only three episodes in, but so far I'm loving it. I'll report back. Here’s the trailer (not safe for work):

Cooking

My most successful culinary accomplishment of the week was making Mango Peanut Chicken Salad, a recipe by Caroline Chambers, which you can find on

's brilliant Substack, the Department of Salad. It was delicious, and the recipe made for multiple meals—with the leftovers tasting even better. Here is the particular post, which also includes a couple of other recipes, along with Emily's account of life with her new puppy, Cookie.That's it for this week. Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

What a potpourri of plenitude! (Sometimes I can't help myself.) Valuable insights on Mantel. I'll be listening to the quartets.