🦉Bird-Bolts and Cannon-Bullets VI

All-listening edition: Podcasts, Nat King Cole, and Ormandy conducts Rimsky-Korsakov

This is the weekly roundup of reading, listening, and recommendations (though this week it’s all listening).

🎧Listening

I don’t listen to as many podcasts as I used to. Who has the time? As the medium has become more commercialized and the shows more slickly produced, it has become less interesting to me. However, there are still a few that I make time for, and these are my two favorites:

The Partially Examined Life

This is the only podcast that I actually pay for, and it’s worth every penny. Essentially, it’s a group of guys who were philosophy PhD students a few decades ago but left the field for various reasons. In 2009, they began to record this show in an attempt to recapture what they valued about their studies. Here’s a description from their website’s FAQ:

The Partially Examined Life podcast is our attempt to recreate the good old days when we'd meet up after a seminar to drink beer and talk shop or get some teaching yas out where students couldn't talk back. We're recording it to share our joy in "doing" philosophy with all who care to listen (and occasionally ranting bitterly about the profession that we so long ago escaped).

Their lead-in to every episode is something like: “Welcome to The Partially Examined Life, a podcast by some guys who were once set on doing philosophy for a living but then thought better of it.” I think that these descriptions sell them a bit short: since 2009, they have accumulated a remarkable body of work exploring the history of philosophy from the pre-Socratics to the present. Their conversations are deeply informed and yet approachable for the non-expert. The podcast has hosted an impressive array of guests over the years, including some major contemporary philosophers—though most of my favorite episodes include just the four hosts: Mark, Wes, Seth, and Dylan have developed a brilliant chemistry and conversational dynamic—funny and insightful but never veering into pretension or pedantry. They have also built a network of podcasts beyond their flagship, including Closereads, Nakedly Examined Music, and Pretty Much Pop. I must admit that I can’t keep up with all of them and stick mostly to the mother ship, though I’ve selectively dipped into the others and enjoyed them as well.

In addition to being vastly entertaining, the show has also proved an invaluable resource for me. My academic background is in literary studies, and while that has included training in critical theory and aesthetics, my philosophical academic CV amounts to a handful of undergraduate courses from over thirty years ago. PEL has provided me with a curriculum and study guide for the history of philosophy and has made a huge difference in my teaching and scholarship. It has especially helped to provide a greater philosophical grounding for my course on the history of literary criticism, which I teach every year.

While much of their material is now behind the $5-per-month paywall, you can get a good sampling on your podcast app. I recommend poking around their excellent website and blog to get a feel for what they do. If you share the interest, then you may well find that it’s worth a few bucks too.

No Such Thing as a Fish

Though No Such Thing as a Fish is totally different from PEL, I would imagine that their Venn diagram of people who might enjoy both would show quite a bit of overlap. It’s another panel show, in which four writers and researchers from the BBC tv program QI each provide a strange or interesting fact, which the panel then discusses. While it is sometimes enlightening, it is always uproariously funny. While the last few months the show has been missing the incomparable Anna Ptaszynski, who has been on maternity leave, they have been making up for it with a series of stellar guests, including most recently Neil Gaiman, who talked about the connection between the invention of the bagel and the history of antisemitism in Poland (granted, a rather grim topic on its own, but as always, the conversation spiraled out through a web of related and often bizarre facts).

Sample facts:

Archeologists have discovered that wiener dogs (modern-day dachshunds) were employed in the glory days of the Roman Coliseum, though we are not quite sure how. (Acrobatics? Combat? Rat hunting? Horrifying sex shows?)

The biggest PDF that you could send via email would be larger than Belgium if printed out.

In 1782, a woman found a drag performance in the context of The Beggar’s Opera so hilarious that she literally died of laughter—three days later. Apparently, she kept laughing the whole time.

Give it a couple of episodes to get to know the panel and their conversational style: Andy, the self-deprecating one, who takes delight in his fascination for apparently boring facts about things like lichen and moss; Dan, the Australian with a love for strange memorabilia and often questionably sourced “facts”; Anna, perhaps the funniest of the bunch, who always puts Dan in his place; and James, the charming northerner, who often breaks out the most side-splitting one-liners. (Indeed, I must warn you that at least once per show you will not be able to contain your laughter, so perhaps don’t listen to this in the library or surreptitiously during a church service.)

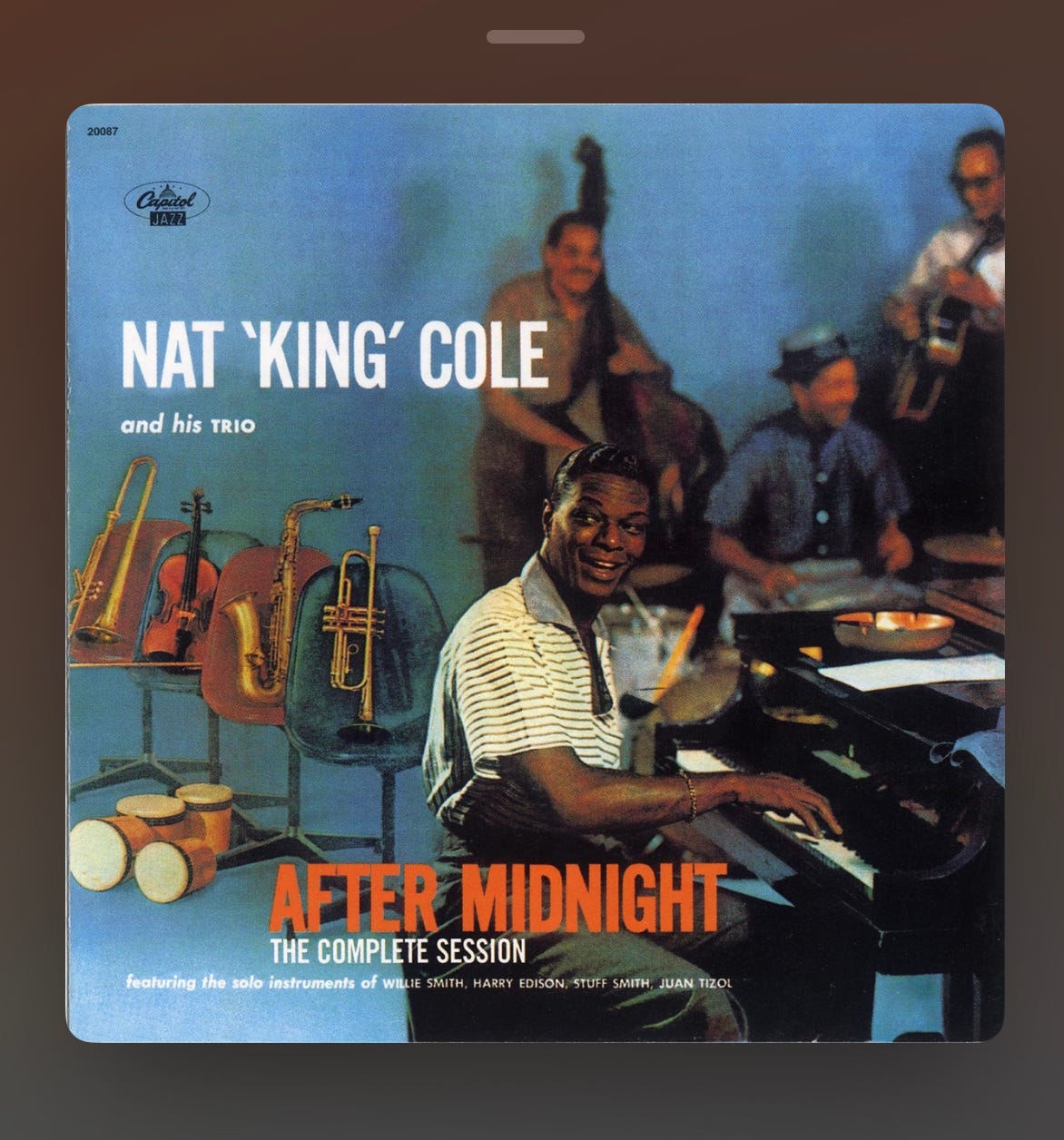

Nat King Cole: After Midnight (The Complete Session)

Nat King Cole could be called the Jackie Robinson of music and television, though he doesn’t receive as much credit for being ground-breaking as his great athletic contemporary. He was the first African-American man to host a national television program, and his trio, when they were signed with Capitol Records, was the only black group on the label which would go on to release The Beatles’ albums in America.

Of course, everyone knows that voice—silky smooth but with a bit of husk in the lower register, impeccable control, perfect phrasing—but not everyone knows that he was also a great jazz pianist and small-group leader. His early recordings with his legendary drummerless trio (guitar, bass, and Cole’s piano) are delightful and swing like nobody’s business despite the lack of percussion. These early records are completely different from his more famous recordings from the late 50s and early 60s, many of which are gorgeous but are sometimes overly produced and tend toward cloying orchestration. And, of course, the later recordings are all about his voice, with his piano chops almost absent.

For my money, After Midnight is the perfect Nat King Cole record, because it takes what is best about the early and the late recordings and combines these elements into a swinging, beautiful masterpiece of both jazz and pop. Nat is in fine voice, and he is accompanied by his trio (John Collins and Charlie Harris) rather than an orchestra, and supplemented by Lee Young’s drums and a star lineup of soloists, including Willie Smith (alto sax), Harry “Sweets” Edison (trumpet), Juan Tizol (trombone), and Stuff Smith (violin). The sound quality is also better than the early trio recordings, with Capitol’s nicely focused mono, so well recorded that you don’t even miss the lack of stereo.

While there is no footage that I could find of this lineup, here is a much earlier performance (circa 1946) from the glory days of his trio:

Irresistible, isn’t it? While I love all of those early trio recordings, a certain sameness creeps in after a while, I think because the lack of a drummer means that the guitar and bass stay mostly devoted to rhythm—which is great, and it swings, but there is something of a lack of variety in the texture. And it’s the variety of texture that makes After Midnight stand out, both from the addition of the drums and from the fabulous performances from the virtuoso soloists. Nat’s voice is also at its finest, and his pianistic dexterity is on display.

We can only weep when we contemplate how young Nat was when lung cancer took him from us. He was only 45. We are lucky to have his recorded legacy, and this record in particular.

Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra: Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, Russian Easter Overture, Capriccio Espagnol

What does this album of pieces by Rimsky-Korsakov have in common with Nat King Cole’s After Midnight, you may ask? Answer: the genius of late-50s and early-60s audio engineers. While After Midnight was on Capitol and in mono and this record by Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra was on Columbia and in stereo, they both have a warmth and a presence that is surprising, considering the relatively primitive state of recording technology.

This is actually true of most of Ormandy’s recordings on Columbia, going back even to the mono years—as well as for the recordings of his great contemporaries on the same label, George Szell and Bruno Walter.

These days, Ormandy does not enjoy as elevated a reputation as Szell or Walter, but he deserves such accolades. He built the Philadelphia Orchestra into one of the world's great ensembles during his 44-year tenure with them. He was a brilliant technician, but he also created the sort of enveloping warmth of sound that is no longer so fashionable in this age of historically informed performance practices. (As the music critic David Hurwitz has noted often, no one could have been more “historically informed” than Ormandy, Szell, and Walter, all of whom traced their lineages to the orchestral traditions of the nineteenth-century: Walter was Mahler's assistant, for heaven’s sake.)

Ormandy's generous approach is perfect for this music with its inherent showiness and drama (with elements of orientalism, much more apparent now than they were in 1962). Scheherazade is, after all, one of the great showpieces of the repertoire, and a great vehicle for a violinist concertmaster. This is one of the best of the literally hundreds of recordings of the piece—dreamy and warm, exciting but precise. But don't sleep on the other two pieces on the record. The Russian Easter Overture is dramatic and lovely, and the Capriccio Espagnol is, if anything, even showier than Scheherazade, complete with rollicking tunes and castanets, all arranged by one of the great orchestrators of them all: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Though he is overshadowed by his fellow Russian contemporary Tchaikovsky as well as his modernist successor Stravinsky, he was as great as both of them in terms of his mastery of orchestral color. (He literally wrote the book on orchestration; I mean literally: he wrote a book on orchestration.) This record is pure pleasure. Listen with good headphones or IEMs to appreciate the mastery of those Columbia audio engineers.

That's all for today’s all-listening edition of the roundup. Perhaps next week I'll give you an all-reading edition to balance things out. What are you reading, watching, or listening to this week? Let me know in the comments.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Let me know, friends. What are you reading or listening to or watching this week?

"What does this album of pieces by Rimsky-Korsakov have in common with Nat King Cole’s After Midnight, you may ask? Answer:" Get the answer and be enriched in the process.