Dear Reader,

This twentieth edition of Bird-Bolts is free for everyone to read. Thanks to those who have supported my work for the past six months. I am glad that you are here. In the new year I will be announcing some exciting new features for paid subscribers, as well as a new extended series, which will be free for everyone. Meanwhile, I hope that all of you enjoy a safe and peaceful holiday season.

Yours,

John

Reading

A few weeks ago I began a series of reviews (which I have not finished—watch this space!) of books that deal in one way or another with the matter of Troy. I was inspired to go back to these books from my reading of Emily Wilson’s remarkable new translation of Homer’s Iliad (Norton, 2023), which I have finally finished. I’ll give you a short version and a somewhat longer version of my review.

Short version: While it does not replace Richmond Lattimore’s as my reference version of the Iliad, Emily Wilson’s is an impressive achievement, and it may, with its accessible language and its narrative momentum, be the translation of choice for teaching the poem in English in the twenty-first century.

Longer version: I do not read Ancient Greek, and so I will leave commentary on the accuracy of Wilson’s translation to the classicists. My critical perspective comes from my reading of the translation as if it were an original poem for readers of English. From that perspective, it often succeeds brilliantly, though it is not perfect.

The main difference you will notice coming from Lattimore’s classic version is in the flow of the verse. While Lattimore uses a six beat line with variable numbers of syllables (and with generous use of dactyls and anapests, his English approximation of Homer’s hexameter), Wilson has chosen blank verse—iambic pentameter. This choice creates a number of novel effects, both positive and negative. Her blank verse participates in the tradition of English epic, with Milton as the most obvious touchstone. It is a form that works idiomatically and naturally in English, but it is strikingly different from the effect of Lattimore’s longer lines.

The best way to demonstrate these differences is with an example. Here is one from Book 24, the famous moment when Priam and Achilles weep together over their respective losses of Hector and Patroclus. Here is Lattimore (N.B. If you are reading this on your phone, the lineation may not be preserved due to the small size of your screen):

So he spoke, and stirred in the other a passion of grieving

for his own father. He took the old man’s hand and pushed him

gently away, and the two remembered, as Priam sat huddled

at the feet of Achilleus and wept close for manslaughtering Hektor

and Achilleus wept now for his own father, now again

for Patroklos. The sound of their mourning moved in the house. Then

when great Achilleus had taken full satisfaction in sorrow

and the passion for it had gone from his mind and body, thereafter

he rose from his chair, and took the old man by the hand, and set him

on his feet again, in pity for the grey head and the grey beard,

and spoke to him and addressed him in winged words . . .

And here is Wilson:

This made Achilles yearn

to mourn his father. With his hand, he gently

took hold of the old man and pushed him back.

Then both remembered those whom they had lost.

Curled in a ball beside Achilles’ feet

Priam sobbed desperately for murderous Hector.

Achilles wept, at times for his own father,

and sometimes for Patroclus. So their wailing

suffused the house. But when godlike Achilles

had had his fill of tears and his desire

to weep had left his body and his mind,

he jumped up from his chair and with his hand

lifted the old man to his feet, in pity

for his white hair and his white beard, and spoke

winged words to him.

The first and most obvious point is that it takes fifteen lines for Wilson to convey what Lattimore accomplishes in eleven, and this allows Lattimore to stay closer to Homer’s lineation. It may be my history with Lattimore’s version that biases me, but it seems to me that he is far superior in these elegiac moments—here and in the laments of Andromache, Hecuba, and Helen that close the poem. When I first read the final book of the poem in college in this translation, I was literally moved to tears.

I don’t weep often when reading, but I think that this response was partly a function of Homer’s narrative structure by which he has reached this moment and the emotional investment I had made in my first reading of the poem, through the course of which I was drawn most to Hector, the object of Priam’s mourning here. But I think that part of the credit goes to Lattimore’s fluid verse, which tends to flow in triplets—dactyls and anapests—and which to my ear conveys sorrow and pathos. But his diction is also more effective; for example: “The sound of their mourning moved in the house.” This gives the sense of the living, tremulous quality of mourning for the dead, as well as the literal vibration of the air created by the sound of lamentation.

On the other hand, Wilson’s declarative pentameter works magnificently for episodes of action and movement, especially her treatment of epic simile, which somehow doesn’t seem to slow things down in her version. From Book 22, the final confrontation between Achilles and Hector:

When Hector saw him, he began to tremble.

He did not dare stay there. He left the gates

and ran away. Achilles sprinted after,

confident of his own quick feet. As when

a hawk, the fastest bird upon the mountains,

swoops easily to catch a trembling dove—

she flutters underneath him to escape,

but he stays close behind and keeps on lunging

towards her with sharp shrieks, intent to seize her—

so eagerly Achilles flew towards him,

and Hector trembled underneath the wall

of Troy and moved his legs at topmost speed.

They dashed beneath the shadow of the wall,

and kept along the wagon track, and passed

the lookout area, the windswept fig tree,

and reached the pair of beautiful clear springs,

the sources of the eddying Scamander.

This makes my heart race, and it is tremendous when read aloud. It seems as immediate and as visceral as my first encounter with Homer all those years ago. Indeed, I encourage you to read stretches of the translation out loud (or perhaps to listen to the audiobook); Homer’s poetic tradition was, after all, an oral (and aural) one.

Ultimately, if you want to get a sense of the range and the power of the poem and (like me) you don’t have Ancient Greek, it’s best to survey a number of translations over the course of a lifetime: Lattimore, Wilson, Fagles, Fitzgerald, Pope, Chapman, Alexander, etc. All of them have their strengths and their critical champions, and they each serve to remind us that this is the most essential of all poems in western literature, that it resonates and speaks to us through everything that follows it. And while I will still probably turn most frequently to Lattimore, I like to imagine that if he were still alive, the great poet and translator would, like Homer and Virgil to Dante in the fourth canto of Inferno, welcome Emily Wilson as one of a select fellowship of poets.

Listening

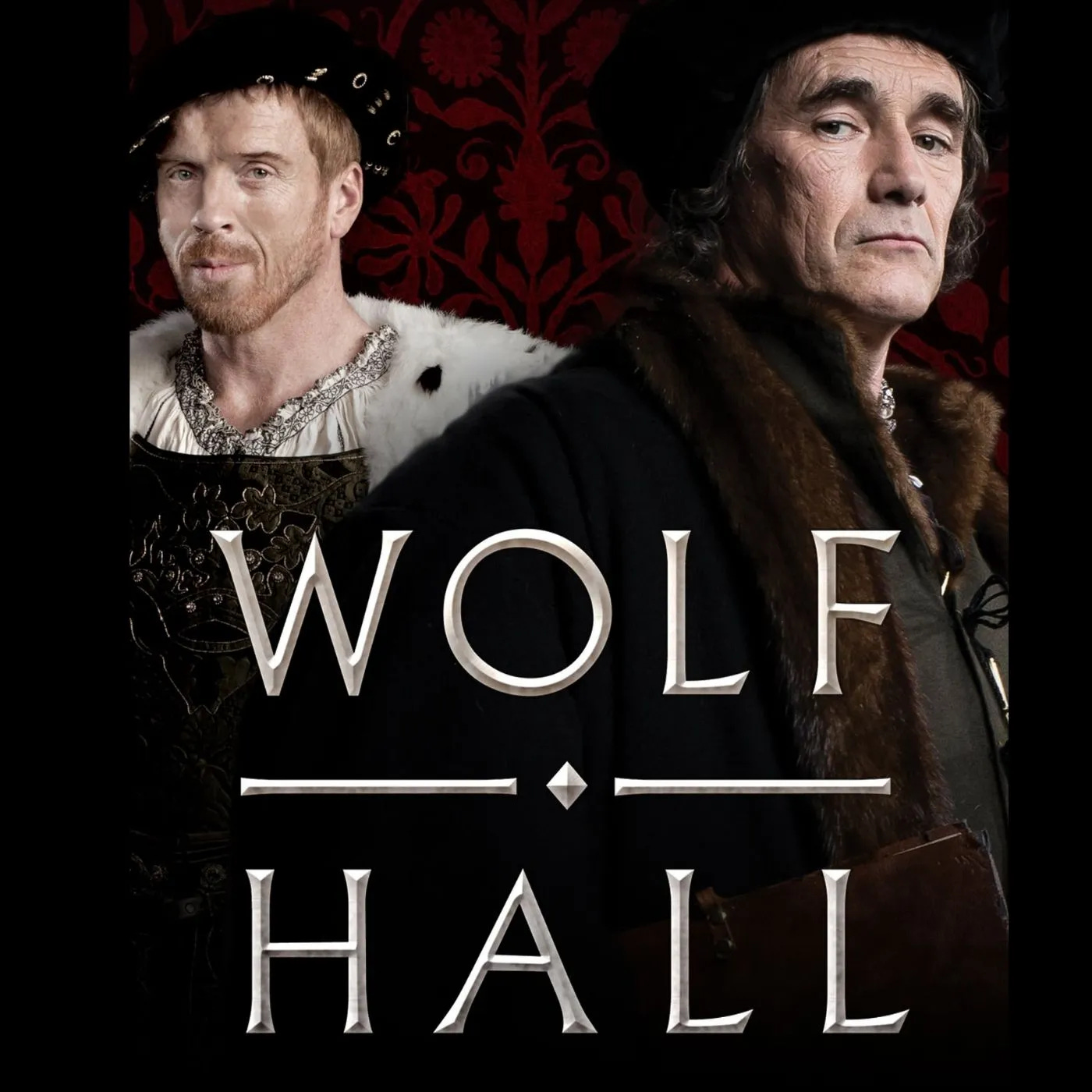

There are no new additions to the Rotation Playlist this week, but I do want to focus on its opening selection: Debbie Wiseman’s soundtrack to the television adaptation of Wolf Hall, which will remain at the head of the playlist through the rest of the year and into the beginning of 2024 in anticipation of

’s slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell books (#WolfCrawl).To some, Wiseman’s soundtrack may seem repetitive as an independent listening experience, that is, without the visual drama that it accompanies. It is insistent, almost obsessive, in its use of a small handful of melodic fragments that repeat cyclically. For this compositional method, however, there are illustrious precedents: Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in C Minor comes to mind, or Philip Glass’s entire career.

If you have seen the television series, then the soundtrack will inevitably bring its unique visual presentation and understated acting to mind, and this is not a bad thing. The instrumentation is spare, and the tone is mostly dark and probing. I have found listening to it independently of the television show to be a meditative experience, and also that listening to it while I work or read actually intensifies my focus, which perhaps echoes the intense focus of Thomas Cromwell, Master Secretary himself.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

The Lattimore translation remains for me, as does my love for _The Iliad_.

Thanks for this considered judgment, John. I'm happy for it in part because it helps me decide to stick with Lattimore in my next reading. Or maybe I'm just using it for confirmation bias. :)

Also, I was reviewing translations in preparing for the War and Peace slow read. I came upon, on my own, the site that @Simon Haisell recommends to help people choose: https://welovetranslations.com/2021/08/31/whats-the-best-translation-of-war-and-peace/

I have the decades-old translation by Rosemary Edmunds, now out of print, and I wanted to see, again, if I should be tempted to another. I ended, again, confirmed to stick with it. A primary reason is my wish to be drawn into the historical-cultural world of the original work, not to have the work brought into the present. I sought that in choosing the Lattimore translations of Works and Days and the Theogony I'm currently reading. Some of the more current and popular W&P translations, like the Briggs, seek that updated sensibility and I don't want that. I already had that sense about Wilson and The Iliad. (You can tell me if I'm overstating the case there.) In the passage you offer for comparison, the slower, grander, more solemn cadence of the Lattimore is very much to my point.

BTW, on Tolstoy again, the Edmonds translation is often identified as a 1957 translation. However, my Penguin Classics edition is a 1978 revision by Edmonds. She notes that it's based on a 1962-63 definitive revision for the Russian collected works. She writes that it includes 1885 corrections founded in misreadings of Tolstoy's awful handwriting and insertions, and his own careless if not somewhat indifferent editing of his own work. I should think other English translations post '63 were based on that revision, but I know that a couple of popular translations actually start from the 1923 Maude translation.