Burning Books and Burning Bodies in Hilary Mantel’s *Wolf Hall*

. . . And in 21st-Century America (part one)

Why were heretics burned in medieval and early modern Europe? Burning at the stake is a method of execution with a long and sordid history, and it has been used to punish a variety of crimes, but why has it been associated especially with heresy? Perhaps the fearfulness of the public spectacle was considered an effective deterrent to potential heretics, more so than the relatively quick executions by public hanging or beheading. However, even more painful and disturbing means of execution have been devised, such as the elaborate spectacle of drawing and quartering to punish the failed assassin Damiens in 1757, whose death is famously described by Michel Foucault at the beginning of Discipline and Punish, his brilliant history of the exercise of political power on the body. Drawing and quartering was also sometimes used to punish treason in England in the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, but heretics were burned. Perhaps the flames were meant to anticipate the fires of Hell that awaited the condemned in the next world. Perhaps the annihilation of the corpse was meant to convey the impossibility of the resurrection of this particular body in the last days.

While Hilary Mantel’s magnificent novel Wolf Hall does not exactly seek to provide an answer to this question, the book offers up execution by fire as a phenomenon that forces us to contemplate the relationship between the burning body and selfhood, as well as the implicit correspondences between the heretical text and the heretical body: as bodies were burned, so were books. This is a connection that we would do well to consider in 2023 as our postmodern inquisition (in Florida, in Russia, in Hungary, and elsewhere) seeks to eradicate what it sees as heresy, as it attempts to ban certain books and ostracize people whom it views as ideologically unacceptable. While authoritarians like Orbán and DeSantis are not (yet) literally burning books or bodies, they view ideology and personhood as essentially equivalent—the self as a readable text that must conform or be eradicated.

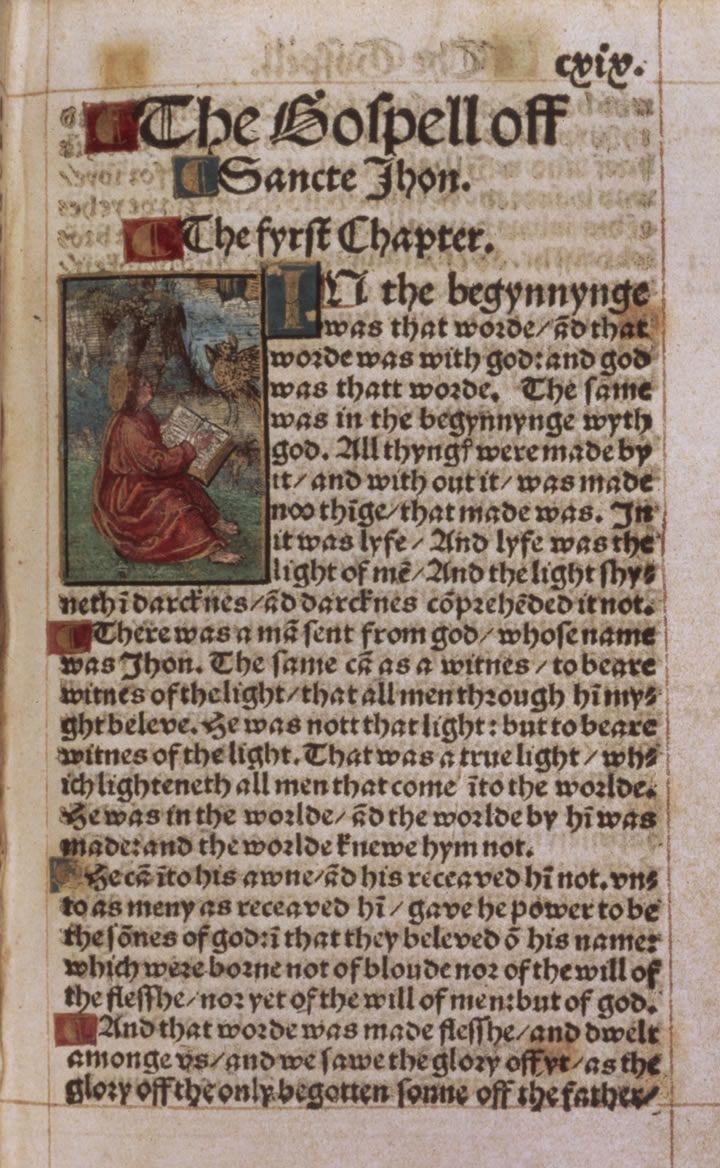

Mantel, who left us far too soon when she died last year, has offered us a window of understanding into this reactionary view of the world in this book, the first of three novels that chart the extraordinary career of Thomas Cromwell, King Henry VIII’s right-hand man. Cromwell opposes these reactionary forces in Mantel's telling. He remembers watching as a child the burning of a Lollard and helping her surviving friends collect the scant physical remains of the victim—a body burned down to a morbid essence: “It was just splinters of bone now, and thick sludgy ash.” Lollards were followers of the medieval Oxford academic John Wycliffe, and they produced an illegal translation of the Bible—illegal because any translation other than the Latin Vulgate was forbidden. Their faith held that the everyone should be able to understand scripture, not just those who could read Latin, and hence their faith and the text that they revered were ideologically inextricable. If faith is located within some kind of essence of selfhood and potentially is revealed in moments of bodily peril, then burning, or the threat of burning may expose (or destroy) this essence. A body burned and annihilated to this extent reveals nothing of the self that has been consumed—just as a burned book reveals nothing of its text.

In Wolf Hall, heretical bodies are living texts, defined in their essence by the possession and assimilation of William Tyndale’s English translation of scripture. For Thomas More, whose persona in the novel is quite different from that of the More whom Robert Bolt presents in his play A Man for All Seasons, these bodies, like the texts they possess, must be burned. Mantel’s More is a fanatic, despite his massive intellect. Early in the novel, Cromwell contemplates More’s absolute certainty of his own righteousness:

He never sees More—a star in another firmament, who acknowledges him with a grim nod—without wanting to ask him, what’s wrong with you? Or what’s wrong with me? Why does everything you know, and everything you’ve learned, confirm you in what you believed before? Whereas in my case, what I grew up with, and what I thought I believed, is chipped away a little and a little, a fragment then a piece and then a piece more. With every month that passes, the corners are knocked off the certainties of this world: and the next world too.

For More, the translated text allows English readers dangerous free rein to interpret for themselves, to discover the flimsy or even absent scriptural foundations for orthodox dogma. These early English Protestants are called "lovers of the gospel" in the novel, or "gospellers," which makes clear that the connection to the text is at the center of their faith. But there is a curious distinction here, at least for the modern reader: early in the novel, the reader is informed that Cromwell has the entire New Testament memorized, and this may seem to indicate that he is, therefore, the ultimate example of a lover of the gospel, a living, breathing biblical text. The text held in his memory, however, is the Latin Vulgate rather than Tyndale's English translation—a distinction that is the difference between being celebrated as an example of learned piety and being burned: "The Cromwell household is as orthodox as any in London, and as pious. They must be, he says, irreproachable."

Lurking behind the story here is the astonishingly rapid historical trajectory through which essentially the same text, the English translation of the Bible, the possession of which could result in public execution in the middle part of the 1530s, would, by statute, appear in every English parish church by the end of the decade, available for all parishioners to read. Mantel attaches a narrative to this trajectory, through which the text of the English Bible and the perceived essence of selfhood for "lovers of the gospel" become inseparable, to the point that in some contexts the categories—text and self—merge into one.

Early in Wolf Hall, Cardinal Wolsey, in his role as Lord Chancellor, appears as a moderating force against the zealous efforts to hunt down heretics by More, and this moderation is removed with the fall of Wolsey from royal favor and the ascendance of More as Lord Chancellor. Before Wolsey's fall, Cromwell keeps him informed,

so that when More and his clerical friends storm in, breathing hellfire about the newest heresy, the cardinal can make calming gestures, and say, "Gentlemen, I am already informed." Wolsey will burn books, but not men. He did so, only last October, at St. Paul's Cross; a holocaust of the English language, and so much rag-rich paper consumed, and so much printers' ink.

Wolsey burns these books to keep both the anti-Lutheran zealots and the so-called heretics in check. Unlike More, Wolsey sees a categorical difference between texts and the people who possess them.

Set against this emerging association between text and the Christian subject is a traditional medieval church that defines the self through public and private actions, through performance, prescribed and illicit: participation in the sacraments, the paying of tithes, prayer, veneration of relics, sins both public and private. Aspects of these performances could be hidden from the public—More’s self-scourging and hair shirt, for example—but could also be manifest in more or less visible adornments of the body, even for those outside holy orders. It is worth examining an extraordinary, perhaps exaggerated example of such a traditional self-construction in order to understand the enormity of the contrast with the reformers. The Duke of Norfolk goes so far as to wear a variety of relics about his person in the superstitious hope that they will protect him from the prying of the spirits of the dead:

. . . indeed he rattles a little as he moves, for his clothes conceal relics: in tiny jeweled cases he has shavings of skin and snippets of hair, and set into medallions he wears splinters of martyrs’ bones. “Marry!” he says, for an oath, and “By the Mass!,” and sometimes takes out one of his medals or charms from wherever it is hung about his person, and kisses it in a fervor, calling on some saint or martyr to stop his current rage getting the better of him. “St. Jude give me patience!” he will shout; probably he has mixed him up with Job, whom he heard about in a story when he was a little boy at the knee of his first priest. It is hard to imagine the duke as a little boy, or in any way younger or different from the self he presents now. He thinks the Bible a book unnecessary for laypeople, though he understands priests make some use of it. He thinks book-reading an affectation altogether, and wishes there were less of it at court.

There are several striking aspects of this description. Perhaps most obviously is the extent to which the duke deploys fragments of dead bodies, which he imbues with magical properties in his imagination, in order to protect his own body from harm. Of course, these almost certainly are not fragments of the actual bodies of the saints and martyrs to which they are attributed, since the mass production of fraudulent relics by the various holy orders is a leitmotif through all of Mantel’s Cromwell novels. (In Bring Up the Bodies, the second novel in the trilogy, Cromwell hears of the skeletal remains of an elephant acquired by the monks of Westminster, apparently for the production of holy relics.) The fact that most of these relics are fraudulent indicates the understanding by those in the know that their protective aspects have nothing to do with connections to actual saints and martyrs, but rather with the credulity of their wearers. The body, in this case, becomes a site for the external expression of the beliefs, desires, and fears of the faithful. Also, the duke’s verbal invocations, while habits of speech, suggest a belief in the power of the dead to intervene in the world. Like his relics, this belief is confused: he does not even invoke the person he means to invoke. But again, this mistake is immaterial, since the connection to the narratives of scripture or saints’ lives is tenuous and tangential; what matters is the ritual of invocation rather than any sort of textual knowledge. His disdain for reading, therefore, as well as his lack of interest in the biblical text, is a natural extension of a faith that privileges the possession of relics and the constant, performative and ritualistic communion with the dead over any sort of internalized scriptural knowledge or studious piety.

The signs of the new, proto-Protestant faith, on the other hand, may be hidden from view, and devotion to scripture is not dependent upon a particular object: one copy of the scripture may be replaced by another, or the text, whole or in part, may even be held in the mind without a physical object. Cromwell, therefore, moves through the novel with what we might call a kind of “plausible deniability,” as he maintains a household that appears orthodox, even as he secretly reads Tyndale’s translation, as well as the forbidden works of Martin Luther. This ability for the gospellers to conceal their faith, for the body to hide this essential aspect of selfhood, is what justifies the zeal with which More and his people search the homes of those suspected of heresy for banned texts, and especially for biblical translations. When Cromwell’s friend Humphrey Monmouth’s home, where Tyndale had once lodged before fleeing to the continent, is raided, “it is clear of all suspect writings,” and, therefore, “they have to let him go, for lack of evidence, because you can’t make anything of a heap of ashes in the hearth.” Again, a book, like the body, yields up no text after it has been burned.

It is this secretive assimilation of texts, this potential merging of the text and self in private, essentially private reading, that terrifies authoritarians of all stripes, from the sixteenth century to 2023. Again, it is no coincidence that DeSantis's fascists in Florida seek to ban books in conjunction with their attacks on the LBGTQ+ and African-American communities. They seek to whitewash history of anything that threatens their ideology, of anything they perceive as "indoctrination" (i.e. independent thought or expression or identity). This is why they target school libraries and academics as well, just as Thomas More's people targeted scholars in sixteenth-century England—because research or reason or independent thought may lead us to inconvenient truths. We may become “heretics” if we read freely.

In part two of this essay on Wednesday, we will look closely at a few of these scholars in Mantel's novel, and we will learn about Cromwell's trained memory, which allows him to hold vast swaths of text in his mind, to assimilate text into the self. Therein lies the promise--and the threat--of education.

Thank you!