Burning Books, the Printing Press, and Artificial Intelligence: Hilary Mantel’s *Wolf Hall*, part 2

The coming textual tsunami of AI

In the first part of this essay, we considered the efforts to ban (or burn) books as deeply connected to the desire to ostracize or eradicate certain classes of people, or certain ways of being in the world—both in Hilary Mantel’s vision of sixteenth-century England and in our world in 2023. Today, I would like to continue this and also to explore the emerging technology of the printing press in Mantel’s novel alongside our cultural obsession with AI. We are currently confronted with the uncanny humanness of text, as well as the apparently textual nature of humanity, as we struggle to distinguish language generated by actual people from that produced by large-language-model artificial intelligence.

At the heart of this struggle is the problem that we feel that we can no longer reliably use our senses or sensibilities to determine what is true, what is human. As we are flooded with text, the word is diluted and devalued. But meanwhile, there are those among us so single-mindedly determined to construct their own realities that they will deny any sort of evidence to the contrary, textual or otherwise.

There are those of this fanatical stripe on both sides of the theological debate in Mantel’s novel. Thomas Bilney’s initial appearance in the novel, for example, marks an instructive contrast to that of the Duke of Norfolk’s outwardly visible superstitions (see the previous post for the example of the Duke):

“Little Bilney” he’s called, on account of his short stature and wormlike attributes; he sits twisting on a bench, and talking about his mission to lepers.

“The scriptures, to me, are as honey,” says Little Bilney, swiveling his meager bottom, and kicking his shrunken legs. “I am drunk on the word of God.”

“For Christ’s sake, man,” he [Cromwell] says. “Don’t think you can crawl out of your hold because the cardinal is away. Because now the Bishop of London has his hands free, not to mention our friend in Chelsea.”

“Masses, fasting, vigils, pardons out of Purgatory . . . all useless,” Bilney says. “This is revealed to me. All that remains, in effect, is to go to Rome and discuss it with His Holiness. I am sure he will come over to my way of thinking.”

The bodily nature of his metaphors is striking: he consumes the scriptures like honey and liquor; they sustain him and make him drunk. Like food, they become part of his body. In addition to Bilney’s loving dedication to the text of the scriptures and his apparent lack of venerated possessions, both of which signal that his faith is defined entirely differently to that of the duke, his touchingly naive devotion to rational discourse sets him apart. Since there is nothing about the efficaciousness of the Mass or the existence of Purgatory in the Bible, all he must do, he thinks, is demonstrate this to the Pope, and reform will happen as a matter of course. This may remind the reader of the letter to the publisher in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, in which Gulliver expresses his surprise that the publication of his book has not resulted in the immediate reform of all aspects of society. Bilney’s interrogators are much more proximate than the Pope, and because, unlike Monmouth, he will not hide his devotion to the English scripture, his textual essence of self, he must be burned, like the text for which he serves as a living, breathing proliferator, a human printing press.

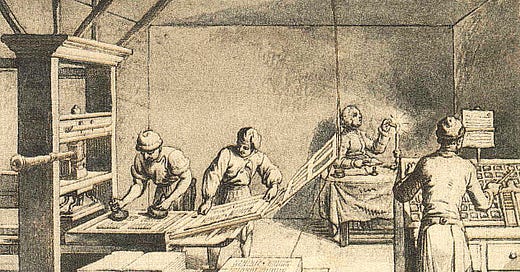

Bilney and the other gospellers burned for heresy play this role almost literally. Bilney is finally taken up and executed after he is caught preaching in the open fields and distributing pages of Tyndale’s gospel among his listeners. The danger for the orthodox is that such pages might be consumed, internalized, that they might become the essence of yet another person. They, therefore, like their distributer, must be burned. Another proliferator of the gospel, John Bainham, is arrested after shouting out his profession of faith in a church, his copy of Tyndale’s gospel in his hand. Unlike holy relics, which may maintain their power for the believer, whether or not they are damaged or even burned, the pages of the gospel maintain their efficacy only if they remain readable. The printing press, therefore, because it can distribute so many copies so quickly, perhaps faster than they can be burned, is a powerful weapon. More is aware of the dangerous potential of the printing press, as he says to Cromwell: “I thought the cardinal might send you to the fair, to get among the heretic booksellers. He is spending a great deal of money buying up their writings, but the tide of filth never abates.” On the opposite side of the fateful argument, the wife of John Petyt, another gospeller, expresses her defiance in conversation with Cromwell with the same knowledge:

“He cannot lock us all up.”

“He has prisons enough.”

“For bodies, yes. But what are bodies? He can take our goods, but God will prosper us. He can close the booksellers, but still there will be books. They have their old bones, their glass saints in windows, their candles and shrines, but God has given us the printing press.”

This suggests that the body is simply a container for the text—which will continue to proliferate thanks to the God-given printing press—as opposed to shrines and relics, each of which depends on its status as a unique physical specimen. But while Lucy Petyt claims that bodies are, ultimately, irrelevant, Mantel’s novel demonstrates a persistent interest in the relationship between bodies and texts, as well as in the ways in which bodies may assimilate texts.

Cromwell himself serves as a site for this interest, most obviously expressed in his reported memorization of the entire New Testament. When he is approached by one of Anne Boleyn’s ladies in waiting, who is looking for a Bible, someone informs her that “Master Cromwell can recite the whole New Testament.” She replies: “I think she wants it to swear on.” Here, a Bible is required to serve as a kind of magical object, like a relic worn by the Duke of Norfolk, as opposed to a text, and so Cromwell’s textual mastery is of no use. A body can serve as a text, but it cannot serve as a religious relic, at least not until it is dead and sainted. Only a holy book has the potential to be associated with both categories.

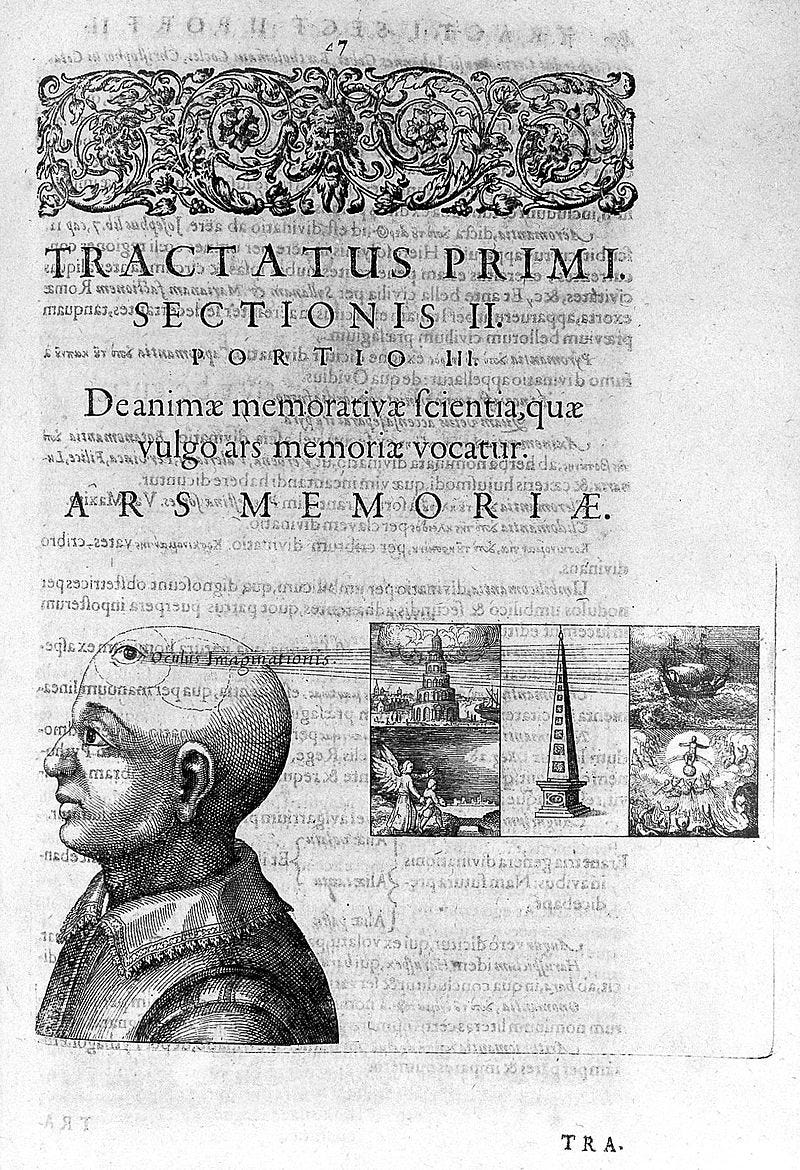

While the association between the biblical text and the essence of the self seems primarily a product of an emerging Protestant subjectivity, the memory system that Cromwell employs is much older, and this allows him to work as a kind of medial figure—in which he resembles the English church under Henry, as it maintained Catholic ritual even as it associated itself with the various continental reform movements. Thomas Aquinas himself, the thirteenth-century theologian and the very personification of orthodox scholasticism, commended the architectural memory system that Cromwell has learned in order to hold texts in his mind.

But the system goes back even further than Aquinas: in an apparent non sequitur in the middle of her narrative, Mantel tells the story of the ancient poet Simonides, who was the only survivor of a dinner party in which the roof caved in and crushed the bodies of the other diners beyond recognition. Simonides was able to remember and identify all of the guests because the seating arrangement was imprinted in his mind: “It is Cicero who tells us this story. He tells us how, on that day, Simonides invented the art of memory. He remembered the names, the faces, some sour and bloated, some blithe, some bored. He remembered exactly where everyone was sitting, at the moment the roof fell in.” I call this an apparent non sequitur because there is no immediately obvious connection to the narrative material that precedes or follows it. It happens at the end of Part Two of the novel, at which point the fall from royal grace of Cardinal Wolsey, Cromwell’s mentor and master, is more or less complete. So, what is this anecdote doing here? There is no definitive answer, but ultimately, it resonates in a number of ways with both the specifics of the narrative and the idea of the self as a kind of text—and also with the bodies and texts in the novel that are destroyed beyond the point of recognition. The passage also is thematically aligned with references to Guilio Camillo’s “memory machine” or “theatre of memory,” which at one point Cromwell tries to buy—though as of yet no working model exists, and no one really knows what it is: “It is likely, he thinks, that we shall never know what his invention really was. A printing press that can write its own books? A mind that thinks about itself?” To the modern reader, of course, the idea immediately calls to mind the computer and artificial intelligence, and thus invokes modern questions of the relationship between the self and memory, the self and text.

In terms of the narrative, the story resonates with Cromwell as the Simonides figure, as he holds in his memory the roles that everyone played in the cardinal’s downfall, either in his defense or his destruction, and he will act on this memory over the course of this novel and its sequel, Bring Up the Bodies, in order to deliver reward and retribution. However, it also invokes an origin story for the idea of memory as text—memory both of experience and of other texts—which motivates the zeal both of the gospellers and of those who pursue them in order to destroy them. The fact that the story is related by Cicero also connects it to the humanist revival of ancient learning that makes possible and animates sixteenth-century debates over biblical translation.

Those of us standing in the twenty-first century looking back have the benefit of hindsight and understand the inevitability of textual proliferation. We know that the book, and eventually the computer, will eventually become cyborg appendages to human memory—easily accessible, widely available, infinitely distributable. Thomas More and his people will fail in his campaign to stop the “tide of filth” created by the printing press, just as Ron DeSantis and those like him cannot hope to eradicate what they see as threatening texts.

In fact, the danger may be quite the opposite. The textual tide produced by the early modern printing press will seem a mere trickle in comparison to the tsunami of AI-generated text that is upon us—and as it begins to seem more and more human. And after all, that original expansion of text brought about by the printing press, that which More calls a “tide of filth” in Mantel’s novel, was at least written by actual humans. Such is not the case with with the emerging textual universe of AI, which is a simulacrum of the human. Those who wish to manipulate us politically, who aim to make us cynical and distrustful of democratic processes and institutions, will have the means to devalue discourse by unleashing a flood of it—threatening to drown out legitimate discourse, to render reading an overwhelming and futile process, to make books less relevant.

In the third and final installment of this piece, I will return to those burning bodies in Wolf Hall and explore the connections between these textual martyrs and our understanding of mortality.

Great observation!

I wonder if Chaucer understood, to a degree, the connection of self-text when he added his "Retraction" at the close of The Canterbury Tales, distancing his work from any relation of "mystical text" meant to be worshipped or made into a "relic."

Also, I have a question regarding your argument: "A body can serve as a text, but it cannot serve as a religious relic, at least not until it is dead and sainted."

But what if that body is the Pardoner himself? Not only is this wicked man holding encyclopedic knowledge of scripture, not unlike dear Cromwell, but uses it as an excuse to further commit sins of the flesh to himself and others he might benefit from, not to mention his using of fake relics to gain material wealth.

Perhaps there is also a present danger of not only losing oneself to AI and cybernetics, but also to zealots who believe that certain texts can transform them into "living relics" that are meant to purify their environment, and if their means of correction pose a danger to others, then they are absolved of any guilt simply by being a vessel of the mystical text, which they can interpret far better than others.

I am slowly coming to a realization that maybe exposing yourself to text has an immense power to change the self, but it is important not to let the text fully consume the self (lack of humanity) or the connection to others might be severed completely (leading to witch hunts).