Do Austen and Wordsworth Speak to Each Other?

They were contemporaries, but do they share anything? Also, the Stack of the Week

My idea of a personal canon, which motivated this entire little publication, is not of an eternal list brought down from the mountaintop by Moses. Our canons change and develop the more that we read and listen; many new inductees join the party, and perhaps a few go home with a designated driver. (I’m looking at you, Thomas Wolfe—give me your keys.) But Wordsworth and Austen have always been mainstays at the party and will remain until the last of the wine is consumed and the lights are extinguished. Wordsworth may be my favorite poet after Chaucer, and Austen is my favorite novelist—period. I never get tired of rereading them. They are old friends, always there when I need them.

So it’s strange that I never thought of them together before teaching them simultaneously in this English literature survey (the course that I have written about here and here). They were, after all, contemporaries: Wordsworth was born in 1770 and Austen in 1775. Wordsworth lived much longer, but their most productive periods overlapped. (Wordsworth lived until 1850, but his poetic powers sadly waned after 1815 or so, though he continued writing for the duration.)

But they seem to have been ships passing in the night. Wordsworth apparently didn’t care for novels, and Austen’s favorite poets were somewhat more old-school than Wordsworth: Walter Scott, Erasmus Darwin, William Cowper.

So does it make any sense to read them intertextually? Is there anything to say about this juxtaposition? Let’s put a couple of pieces of their writing next to each other and see what we can make of them. Here is Austen from the first chapter of Emma:

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself; these were the disadvantages which threatened to alloy her many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at present so unperceived, that they did not by any means rank as misfortunes with her.

And here is Wordsworth from “Tintern Abbey”:

. . . For nature then

(The courser pleasures of my boyish days,

And their glad animal movements all gone by)

To me was all in all. —I cannot paint

What then I was. The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colours and their forms, were then to me

An appetite; a feeling and a love,

That had no need of a remoter charm,

By thought supplied, nor any interest

Unborrowed from the eye.

These are obviously two radically different modes of writing. Of course, there is the difference between prose and verse, as well as that between third and first person. Let’s take Austen first: her third-person narration is flexible enough that it is able to convey Emma’s consciousness, to present her from subject and object positions simultaneously. In other words, while we might see these tendencies described in this passage as personal flaws (so carefully presented with the qualifiers “rather” and “a little”—almost like the narrator is winking at us), it is quite clear that Emma sees them, to the extent that she does at all, as the advantages of her privileged position rather than “disadvantages which threatened to alloy her many enjoyments.” If you know the novel, then you know that central to its drama is Emma’s developing self-consciousness, her growing into an understanding of herself.

While Austen’s third person is flexible enough to incorporate a quasi-first-person consciousness, Wordsworth’s first-person perspective is able to view the past self objectively through reflection. The youthful self is not conscious of the richness of meditation that memory will provide for the future self. The older self uses time as a lens through which to evaluate his own growth, but also as source of peace and vitality, as nature continues to provide comfort and strength through these different stages of life, a constant support despite shifting subjectivity. Both modes, then, Austen’s and Wordsworth’s, despite their differences, are expansive, able to transcend their apparent limitations, and, furthermore, both modes provide us with this multi-perspectival account of a young mind—full of potential but as yet unformed and unreflective.

This perspectival flexibility also reveals a common interest between our two writers: both are profoundly concerned with the ways in which we change as people as we age and learn from experience, as well as with the mystery of the transformation of consciousness. In Book Two of The Prelude, Wordsworth thinks back on his younger self and writes:

A tranquillizing spirit presses now

On my corporeal frame: so wide appears

The vacancy between me and those days,

Which yet have such self-presence in my mind

That, sometimes, when I think of them I seem

Two consciousnesses, conscious of myself

And of some other Being.

Here is the self removed from the self, observing the past self through memory—but also this “tranquillizing spirit,” which for Wordsworth is the animating force of nature that allows him actually to construct a self out of the random series of perceptions that bombard us from our five senses, as well as a narrative that explains how the self changes and grows. While Austen is not so explicitly concerned with the metaphysical, the spinning out of the plot in Emma grants us insight into the growing self-consciousness of our heroine, as she becomes gradually more aware of those flaws that the narrator presents to us in the first chapter.

For both Wordsworth and Austen, then, the primary human drama is an interior one, which is not to say that it is entirely solipsistic. Wordsworth was well aware of the apparent egotism of writing an epic poem about himself in The Prelude, which may be why he didn’t publish it in his lifetime, and Austen supposedly said of Emma that "I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like." (The authenticity of this statement is doubtful, since it is reported only in her nephew’s memoir, which was published over fifty years after her death.)

But no, this is not solipsism if interpreted properly. For Emma, her developing self-consciousness leads her to real empathy. Arguably, the most important moment in the novel is her internal response to Knightley’s reprimand after she ridicules Miss Bates during the trip to Box Hill. Emma has behaved badly, but she comes to recognize this fact and is mortified by it, and so we come to empathize with her not in spite of but because of her bad behavior and the sincere remorse that follows. Yes, the novel’s dramatic climax, if I am correct here, takes place inside Emma’s head, and, specifically, with her dawning understanding of and concern for the feelings of another.

And if you have read Wordsworth’s poems from Lyrical Ballads of 1798, then you know that empathy is central to his poetics, as he imagines the lives of the rural poor and attempts, through his poetry, to give them voice. Indeed, both Austen’s and Wordworth’s literary innovations were largely concerned with the attempt to inhabit the minds of others despite the opacity of human consciousness. In the famous preface to the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth writes:

So that it will be the wish of the poet to bring his feelings near to those of the persons whose feelings he describes, nay, for short spaces of time perhaps, to let himself slip into an entire delusion, and even confound and identify his own feelings with theirs; modifying only the language which is thus suggested to him, by a consideration that he describes for a particular purpose, that of giving pleasure.

Here Wordsworth suggests that the empathy of the poet extends outwards both to the poetic subjects and to the readers: at the heart of his poetry is the desire to convey the emotions and perspectives of others (and of himself) and so to allow us to feel them at a distance. This is what Aristotle claims is the great power of poetry—his famous catharsis. (I will have more to say about this in the Classroom Journal in the near future—stay tuned.) We feel with Emma; we feel with Wordsworth and with, for example, his “Old Man Travelling” in Lyrical Ballads.

So, yes, I do think that Austen and Wordsworth speak to each other despite their differences. And both of them still have much to say to us in 2023, if we are willing to listen.

The Stack of the Week

This week’s stack is 23 Sherwood Drive by

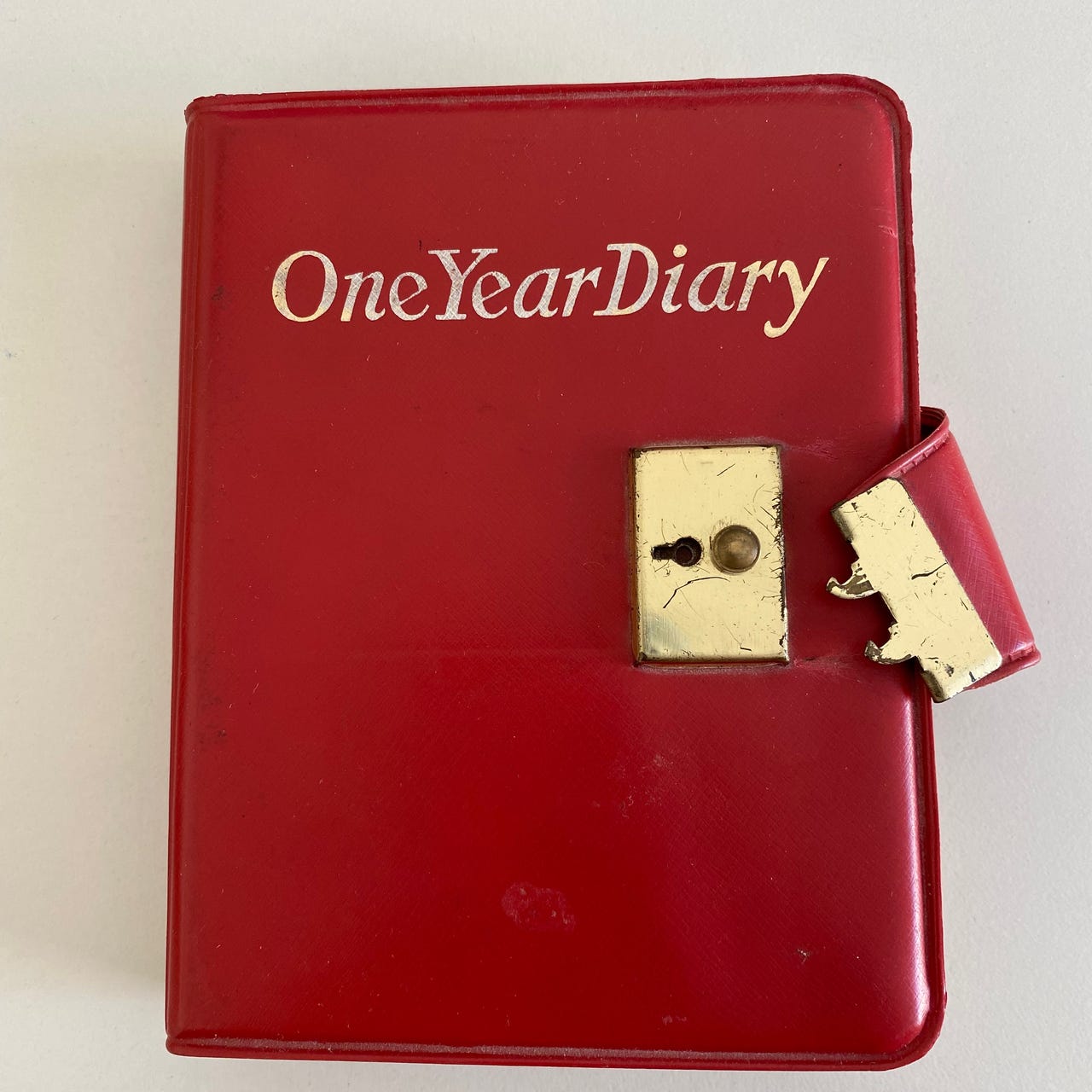

. Jo is a retired academic who has kept journals since the 1960s, and each day she presents entries from different decades, along with commentary from the current version of Jo. The joy of this is getting to know Jo gradually, a bit at a time, at different stages of her life—and also to recognize the changes in our own lives over the decades, much as Austen and Wordsworth equip us to do. Jo’s journal has become a welcome daily presence in my own life, along with her good humor and her “spots of time” (as Wordsworth would call them) from 1964 to the present.That’s it for today. Please do check out Jo’s stack; you will thank me later. And if you haven’t read Austen or Wordsworth, then what are you waiting for?

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Thanks, John, for reminding me that they are contemporaries. I seem to forget! Both Austen and Wordsworth shared profound sensibilities about the things that mattered most to them -- human nature for Austen and the world of nature for Wordsworth. While I'm probably more like Wordsworth in my dreamy reveries of nature, I might wish to be more like Austen taking on society with clear-eyed wit and incisive humor. In other words, she makes me laugh, and I need to do more of that.

Love this. I agree with you and Austen scholar Jocelyn Harris that there is much to learn by exploring Jane Austen as a Romantic - previously she perhaps didn't fit the demographic! But her mind and art absolutely interact with the Romantic poets. (She also gently ridicules them, in Persuasion, yes? But that only goes to show her attention to them.) It also brings to mind Fanny Price's, and other heroine's, spiritual musings and communions with Nature, which are poetic and profound.

Thank you for this fascinating, fun discussion!