English Majors Will Save the Freaking World

An introduction to this fall’s Classroom Journal (part 3)

What is literature? What does it do, and what is its function? What is the relationship between literature and the world? How do we define and categorize literary form and genre? What is the responsibility of the writer? How can women respond to a predominantly male literary canon? How can people of color respond to a predominantly white literary canon? What might constitute productive (or ethical) strategies of literary interpretation and analysis?

I put these questions right at the top of my syllabus in my course on the history of literary criticism. My students are senior English majors, most of whom chose the field simply because they love to read. It's an excellent reason to pick a major, whatever your parents might tell you. It's certainly why I chose it when I switched my major from music to English, lo, these many years ago. You should certainly major in something that you like, because despite what the people in the business school would like to tell you, most students will end up in a career field either unrelated or only tangentially related to their major. I'm the exception, largely because I never really wanted to stop going to school.

But despite the fact that we like to read, and to us that's a good enough reason to justify the field, at some point we need to ask these big questions, because they are not simply abstract. As funding for education in general and the humanities in particular is on the wane, it is vital for those of us in the field to articulate arguments about the value of what we study. Humanities programs are being cut mercilessly across the country because they are not viewed as "practical," even though humanities majors are better than anyone at assimilating, analyzing, and communicating complex ideas across a wide spectrum of subjects. They just happen to acquire these skills by reading old books and writing about them, which most of those in the professional schools, and to a greater and greater extent university administrators, view as pointless activities. Literature is passé. Just this past week, West Virginia University, a flagship state school, eliminated their world language departments, in addition to other major programs, summarily dismissing faculty and leaving dedicated students without a field. Do you think that they will be cutting football next? (I’ll pause for you to drink some water after laughing so much.)

This dire situation is why the history of literary criticism, to me, is not just a course on abstract, theoretical questions: it is a call to action.

We shouldn’t panic, however. This attack on the poets is nothing new—far from it. We begin the semester with Plato (actually, we sort of begin with Gorgias, but more on that in the next couple of weeks), because he shows us that literature has been under siege in some quarters for two and a half millennia. Infamously, in Book Ten of The Republic, Plato announces that poetry (by which he means all imaginative literature) should be forbidden in the ideal society, and the poets should be excluded. We will discuss his reasoning for this in detail in a future post, but I’ll give a quick summary: Plato sees poetry as a mimetic, or imitative art, which takes us further away from truth rather than closer to it. In short, he views literature as a pack of lies.

Writers have been grappling with Book Ten of The Republic ever since, which is why I call the first unit of this course “Grappling with Plato.”

We never really leave this first lesson for the entirety of the semester: we all have to respond to these attacks, because we are still dealing with modern versions of them. Thankfully, many brilliant writers have articulated arguments in poetry’s defense.

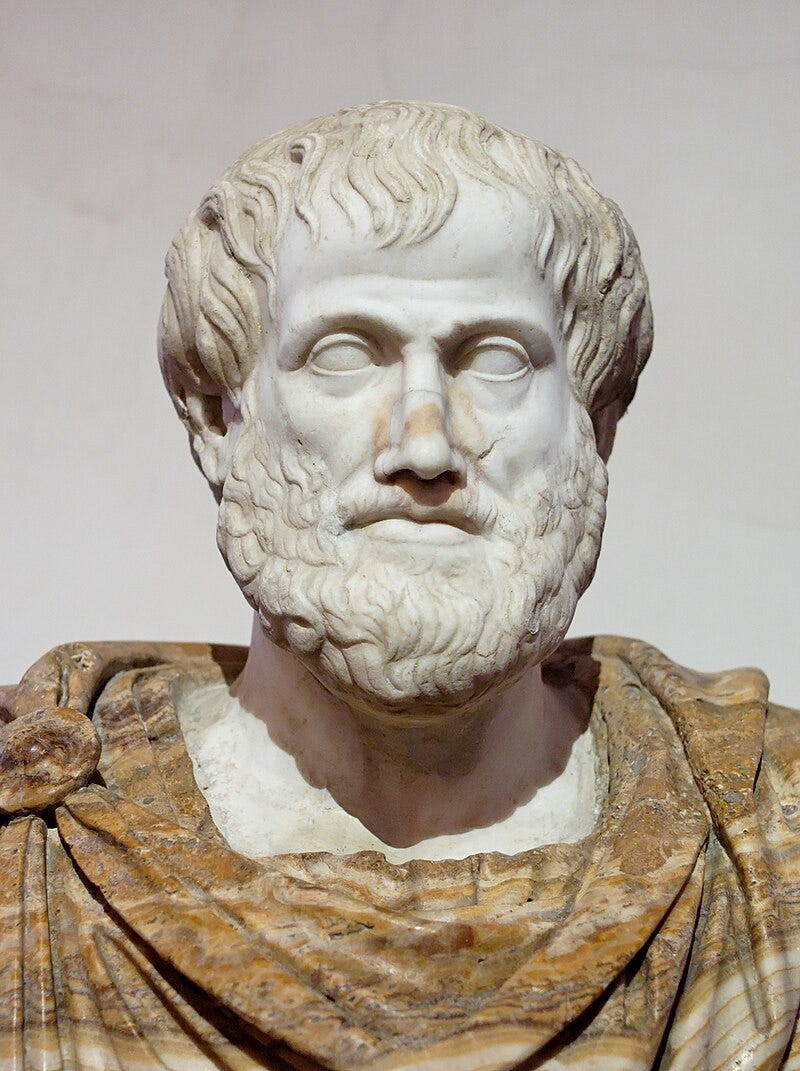

First up in the batting order to take a swing at The Republic’s curveballs: Plato’s own student, Aristotle. In Poetics, Aristotle convincingly (though indirectly) responds to his mentor by taking aim at the heart of the the argument: the value of mimesis, or imitation. For Aristotle, mimesis is the basis of all learning. I’ll save the specifics for later, but Aristotle’s approach is also different. Rather than interrogating the subject with a series of leading questions, which Plato does in the Socratic dialogues, he uses close analysis to draw his conclusions: what is poetry? what does it do? where can we locate its value?

Even though Aristotle makes for drier reading than Plato’s energetic dialogues, as I tell my students, we are all Aristotelians. This is what we do in the university, whether we are studying literature, political science, or biology: we look at evidence, analyze the data closely, and we draw conclusions based on this analysis. This is the Aristotelian way.

A murderer’s row of writers (to continue the tortured baseball metaphor) will build on Aristotle’s response to Plato: Horace and Sir Philip Sidney will argue that literature has profound instructive value; Zora Neale Hurston will demonstrate that mimesis is not mere imitation but that it is culturally vital; Simone de Beauvoir (in perhaps the most devastating attack of all) will expose the deep misogyny at the heart of Platonic idealism.

Eventually, we will arrive at Wordsworth, Percy Shelley, and Emerson, who will make extraordinarily ambitious claims for the importance of literature, indeed for its centrality to the human experience and to a healthy society. Shelley will go so far as to claim that poets “are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

Shelley may be overstating his case—unacknowledged, certainly, but the humanities aren’t too politically powerful these days (or even in Shelley’s time). In fact, it’s comical to hear right-wing claims that leftist humanities scholars are taking over our universities—as if any university administrators listen to the likes of us!

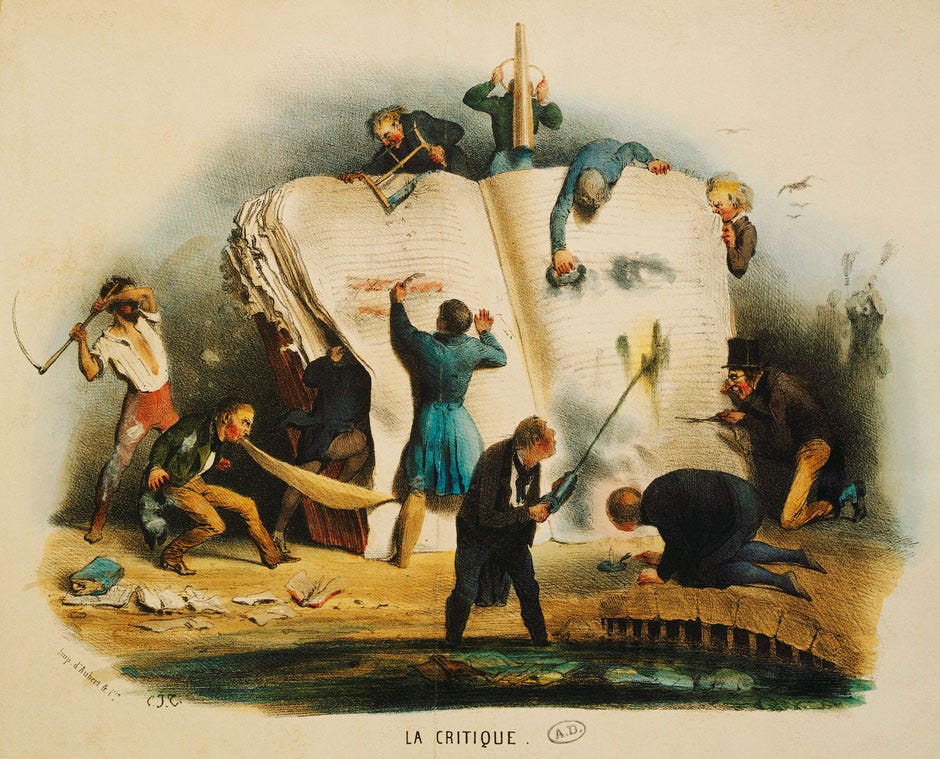

But while we may not be in charge, students of the humanities are uniquely equipped to cope with the instability and uncertainty of our changing world. They are trained to use close analysis to consider major issues. They are adept at assimilating complicated information. They can write without the help of large language models. They are empathetic in a world that is desperately short of empathy. They nourish values that they hold not just reflexively out of deference to tradition, but because of deep reading and thinking. They develop what Oscar Wilde calls “the critical faculty.” (Much more on that later this fall.)

They may not be in charge. They may be underestimated by business schools. They may not make as much money as hedge-fund managers or professional football players.

But given the opportunity, English majors will save the freaking world.

***

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Read John Halbrooks! Poetry and memoir and fiction and the desire to invent lie at the center of the human heart.

William Carlos Williams said,

My heart rouses

thinking to bring you news

of something

that concerns you

and concerns many men. Look at

what passes for the new.

You will not find it there but in

despised poems.

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

—from Asphodel, that Greeny Flower

English major here 🙋♀️