Dear reader,

Here is the long-delayed return to Gulliver. The earlier entries in the series are linked at the bottom of the current post.

Yours,

John

What happens to us when we lose our sense of perspective? Perhaps small, annoying tasks may take on outsized importance, while world shaking events seem distant and irrelevant. Perhaps the universe seems to have reshaped itself as we slept, and we awaken to an alien landscape. Perhaps all of our assumptions about the sort of world in which we have been living are suddenly exposed as false, leaving us unmoored, adrift.

It is easy to laugh at Gulliver as he returns to England from Brobdingnag, as his characteristic denseness resurfaces, but if we read carefully, we may see something of ourselves in him.

Part 3, Chapter 8: Return to England

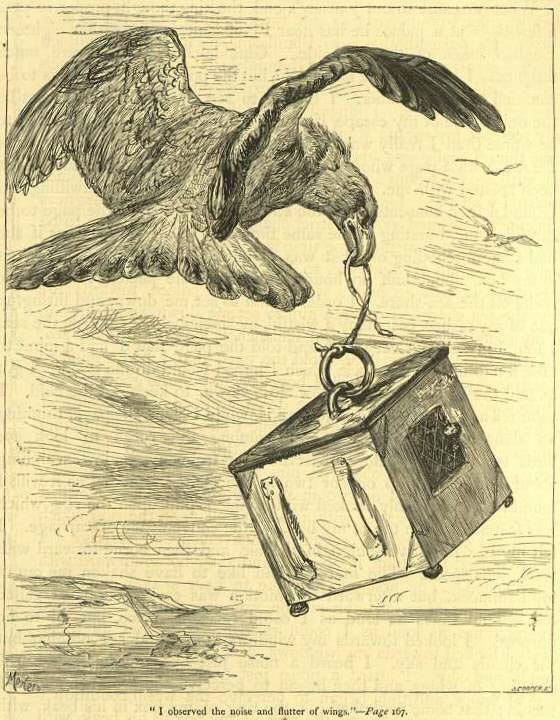

Gulliver's series of potentially fatal adventures enjoys a grand finale as his sojourn in Brobdingnag comes to an end. By this point, Gulliver is accustomed to traveling in his little portable room, equipped with a ring on the top so that Glumdalclitch may carry it about easily. Left unattended for a moment, Gulliver finds himself abducted by a large bird who proceeds to carry his box some distance, the convenient ring in its beak, before dropping him in the sea.

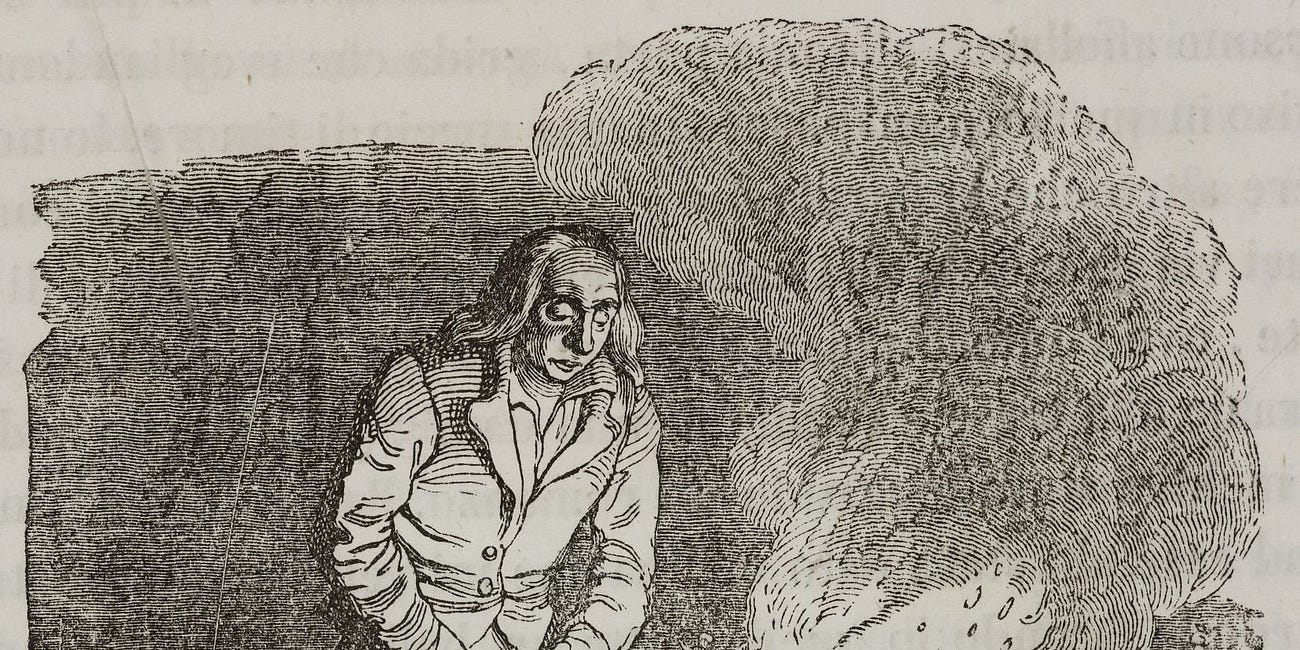

He is rescued by an English ship, and thus begins Gulliver's sequence of challenges of perspective, since he now assumes himself to be rodent-sized—asking, for example, that one of the English sailors simply slip a finger in the ring and pluck his box from the sea and shouting at the top of his lungs in conversation, as he is accustomed to speaking to the Brobdingnagian giants. His perspective shifts violently, however, as he lands in England and travels to his home:

As I was on the road; observing the littleness of the houses, the trees, the cattle and the people, I began to think myself in Lilliput. I was afraid of trampling on every traveler I met; and often called aloud to have them stand out of the way; so that I had like to have gotten one or two broken heads for my impertinence.

When he arrives at his home, he kneels to embrace his wife, assuming her to be Lilliputian in size, but he fails to see his daughter because he cranes his neck to look for her, assuming her to be Brobdingnagian in size.

The world is out of joint. Nothing makes sense:

I told my wife, she had been too thrifty, for I found she had starved herself and her daughter to nothing. In short, I behaved so unaccountably, that they were all of the Captain's opinion when he first saw me; and concluded I had lost my wits. This I mention as an instance of the great power of habit and prejudice.

After we finish laughing, there is a sense of recognition, not only because of the recent political events that have made the world seem very different from what many of us thought it to be, but also because of the dizzying changes we have been through in recent decades—changes so radical that they may be affecting our very evolution as a species.

When I was a child of ten, there were no digital assistants or iPhones; there was no accessible internet; there were no personal computers to speak of; there was no wifi, no AI, no social media; there were no Instagram influencers. The Soviet Union was the threatening eastern behemoth, despite which, the stability of American democracy did not seem to be in doubt. Books and newspapers were all made of paper. My television had a tube and four channels and no means of recording, but I had neither a television nor a telephone in my bedroom.

Like Gulliver, we have awakened in a different world.

Speaking of the time when I was a child of ten, next up will be the continuation of our survey of some of the music of the year 1980, after which we shall follow Gulliver on his third voyage.

And speaking of the 1980s, The Cure has just dropped a new album, and it is very good, so I may sneak in a review of it soon, after I have had a week or two to better absorb it.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Links to earlier installments in this series:

The Second Most Famous Swift

Jonathan Swift is a writer for our time as much as he was for his own—or even more so. As Victoria Glendinning writes in her excellent biography, in "his hatred of militarism, his concern for human rights, social justice and the natural world, his attitude to social welfare—he seems to have leapfrogged the Victorians and most of the twentieth century, a…

For the Love of a Misanthropist

Like Chaucer, that other great English satirist, Jonathan Swift lived in between different spaces and social spheres—between Ireland and England, between the church and p…

Gulliver's Eighteenth-Century iPhone

Welcome to our read-through of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels. Over the last couple of weeks, we have discussed the front-matter to the 1735 edition in this post, and we have briefly covered Swift's biography in this post. Today, we will join Gulliver for the first of his four journeys. We will concentrate on the crucial first two chapters.

The Trauma of Absurdity in Brobdingnag

Welcome back to our Gulliver’s Travels Reading Challenge. Over the last couple of weeks, we followed Gulliver to Lilliput, and now we sail with him to Brobdingnag.

Human Pets and "Odious Little Vermin"

After Gulliver makes his way to court in Brobdingnag, he faces a whole new series of challenges and humiliations, is treated as a pet, and is categorized as one of a species of "odious little vermin." Let's take a brief look at these moments before discussing his absurdly traumatic return to England at the end of Part 2 in our next installment.

Your last full paragraph seems so on target for the time. Gulliver's changes in perspective are abrupt. Though people have talked about it all along, Timothy Snyder observes in a very recent New Yorker essay how we nonetheless failed to take in the full scale of the transformation: "Fascism is now in the algorithms, the neural pathways, the social interactions. How did we fail to see all this?"

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/dispatches/what-does-it-mean-that-donald-trump-is-a-fascist?utm_source=pocket_shared