How to Escape from Your iPhone

Or, an Encomium of the Humble Pocket Notebook

Dear reader,

As I mentioned in my recent responses to Eleanor Anstruther’s 8 Questions, I have developed a tendency to overpromise with regard to my output in this space. So let this be an official declaration (not that anyone has complained—you generous souls): the writing gets done when it gets done, as my personal and professional obligations allow. PCF remains a priority, but I am going to have to stop offering schedules for reading challenges that I cannot keep up with. I realize that this may limit the opportunities for growing PCF’s readership, but I’m fine with that. I do not want to reach the point at which publishing here is a chore rather than a pleasure. I still have a lot to say and a lot to write, and I appreciate your patience.

Those of you who have been awaiting the next Chaucerian installment will not have to wait much longer; I have a draft of the piece on Criseyde nearly completed, though it needs revision. Today’s piece has a lot to do with the writing process, or, more precisely, with the sort of daily writing habits that I have cultivated over the years, so my fellow writers may be interested. I’m also interested in your processes, so please chime in and join the conversation in the comments.

Yours,

John

I have written almost daily in notebooks since I was a teenager and have done so methodically for the last couple of decades. My journal is mostly record of what I have been reading and the music I’ve been listening to, though sometimes it moves into a more personal mode. This is, I think, a common habit for the academic, the professional critic, or even for writers more generally. It is vital to be in constant conversation with what you are reading if you want to write. In fact, Personal Canon Formation, which I began in the summer of 2023, grew out of this habit, since I realized that I had stored up a significant body of critical notes in these decades of journal keeping.

For years, I kept this habit going in A5 notebooks, and there are a couple of shelves of these archived in my office, but some time around 2017, I started keeping the journal on my computer, using a note-taking application called Bear (which I highly recommend for writers who like a clean, distraction-free writing experience). I discovered that an advantage of Bear was that it synced between my computer and my phone, so that I could easily record thoughts when I was out and about. This suited my journal-keeping well, because I have never been the type to write a day’s entry all at once. Rather, I tend to record ideas and notes throughout the day, as they occur to me. When I was exclusively using my A5 notebooks, this meant that if I didn’t have my current volume handy, I would either have to remember to record things later, or I would have to write them on a random slip of paper, which I was likely to lose.

So Bear seemed perfect for this purpose. But there was a problem, which became more and more acute over time and reached a point last year at which I decided that I needed to do something about it.

The problem was that I can do more things on my phone than take down notes.

The iPhone is a beautiful, useful little device, but it also has the potential, as we are all aware, to take over more and more of our lives until it becomes a kind of cyborg appendage.

What do you do when your tool becomes an addiction?

This question popped into my head one day late last year, as I realized that I had wasted two hours watching YouTube reviews of audio equipment. It was a busy day, and I had a to-do list that would be impossible to accomplish, and yet here I was, frittering away the time. While I have always thought that my powers of concentration were considerable, this little piece of metal and glass was leading me to a state of mental atrophy. (It’s no wonder that so many young people, who have never had the chance to nuture their mental focus, have no ability to concentrate at all; it’s not their fault: the tech industry has highjacked their brains.)

The tool that came to my rescue was as humble as it was venerable: the pocket notebook.

In order to maintain the note-taking habit without allowing my attention to be sucked away by Silicon Valley, I had to change tools. I needed a tool that fulfilled one purpose only and did it well.

I decided to replace the phone in my pocket with a notebook and a pen. The phone would be set to silent and stay in my bag. This way when I impulsively reached into my pocket for that dopamine hit, I would find my own writing and blank pages instead of doom-scrolling apps. Everything would go in the notebook: journaling, critical notes, class notes, to-do lists, grocery lists, phone numbers, notes to self, exercise log, etc., etc.

Each morning I would then record the previous day’s entries that were worth preserving in Bear, my trusty note-taking app, on my laptop. This way I preserved continuity with nearly a decade of journal-keeping in that form. The routine had the added benefit of allowing me to process the thoughts and events of the previous day into something like coherence.

The humble pocket notebook had saved my brain.

I had not abandoned the useful aspects of technology. I still used my laptop every day. I didn’t give up my iPhone. But from now on it would serve me rather than colonize my attention. In addition to keeping the notebook in my pocket, I took further steps to make sure that I would maintain independence from my phone:

I began to keep my music on a separate device that was dedicated to that purpose and that purpose only. (Yes, such devices still exist, despite the demise of the iPod.)

I set my phone to silent unless I was expecting a call or knew that family members might need to get in touch with me.

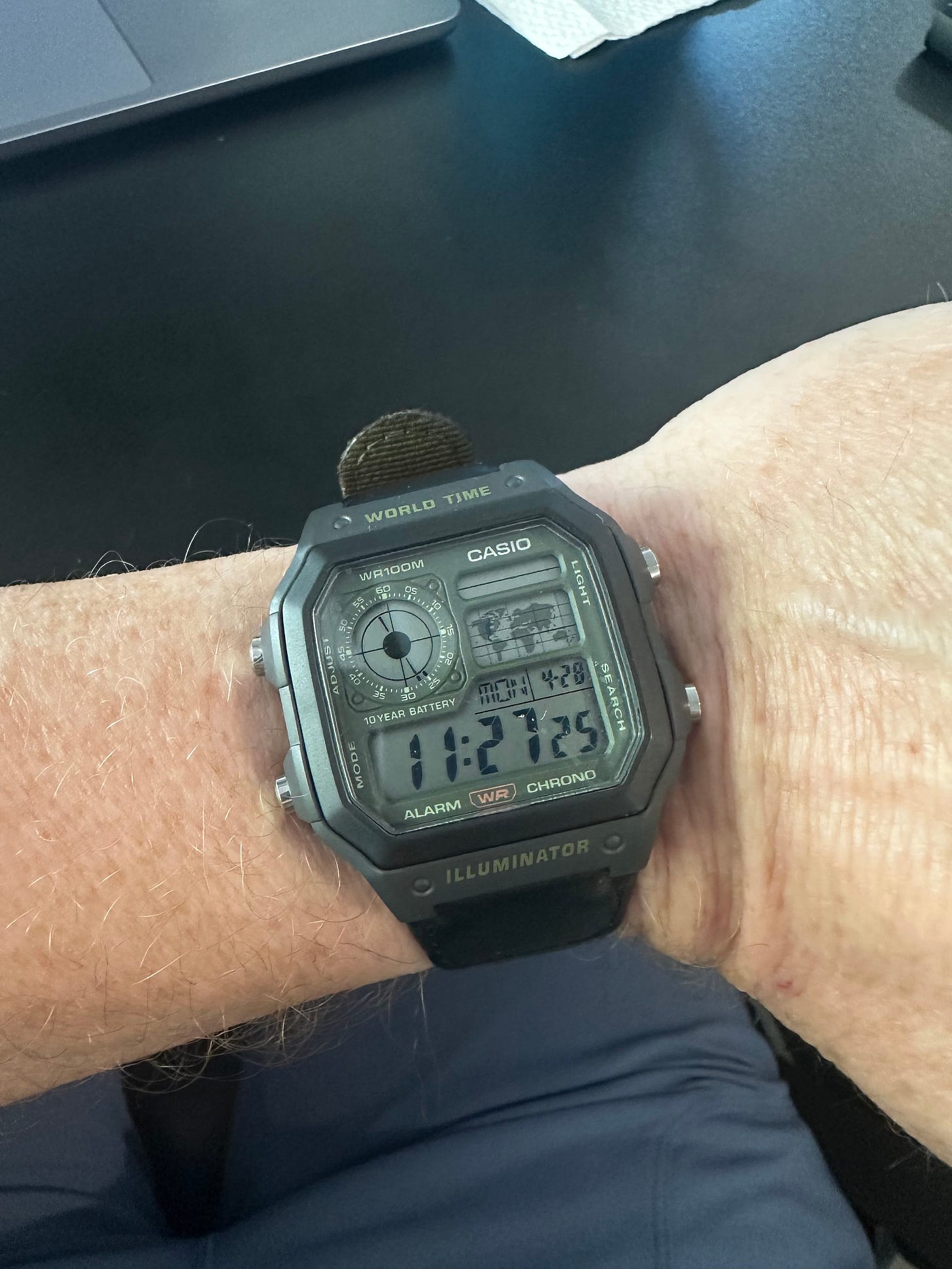

I stopped using an Apple Watch and rescued my old Casio from the dresser drawer. No longer would my watch track my every move or send me a barrage of constant haptic reminders, like an overly attentive nanny. It turns out that traditional watches are much better at being actual watches than so-called “smart” watches. You don’t have to charge a Casio every day (or at all). You can get one with a ten-year battery for less than $30, which will still be ticking for years after your smartwatch has become obsolete and has been thrown into a landfill. Or for a few dollars more, you can get a solar-powered watch and never have to change the battery at all.

So that’s it. Sometimes the simplest solutions work best. Taking notes in a notebook is hardly a profound innovation, but these days it feels more and more like a subversive act.

Further Notes for Notebook Nerds

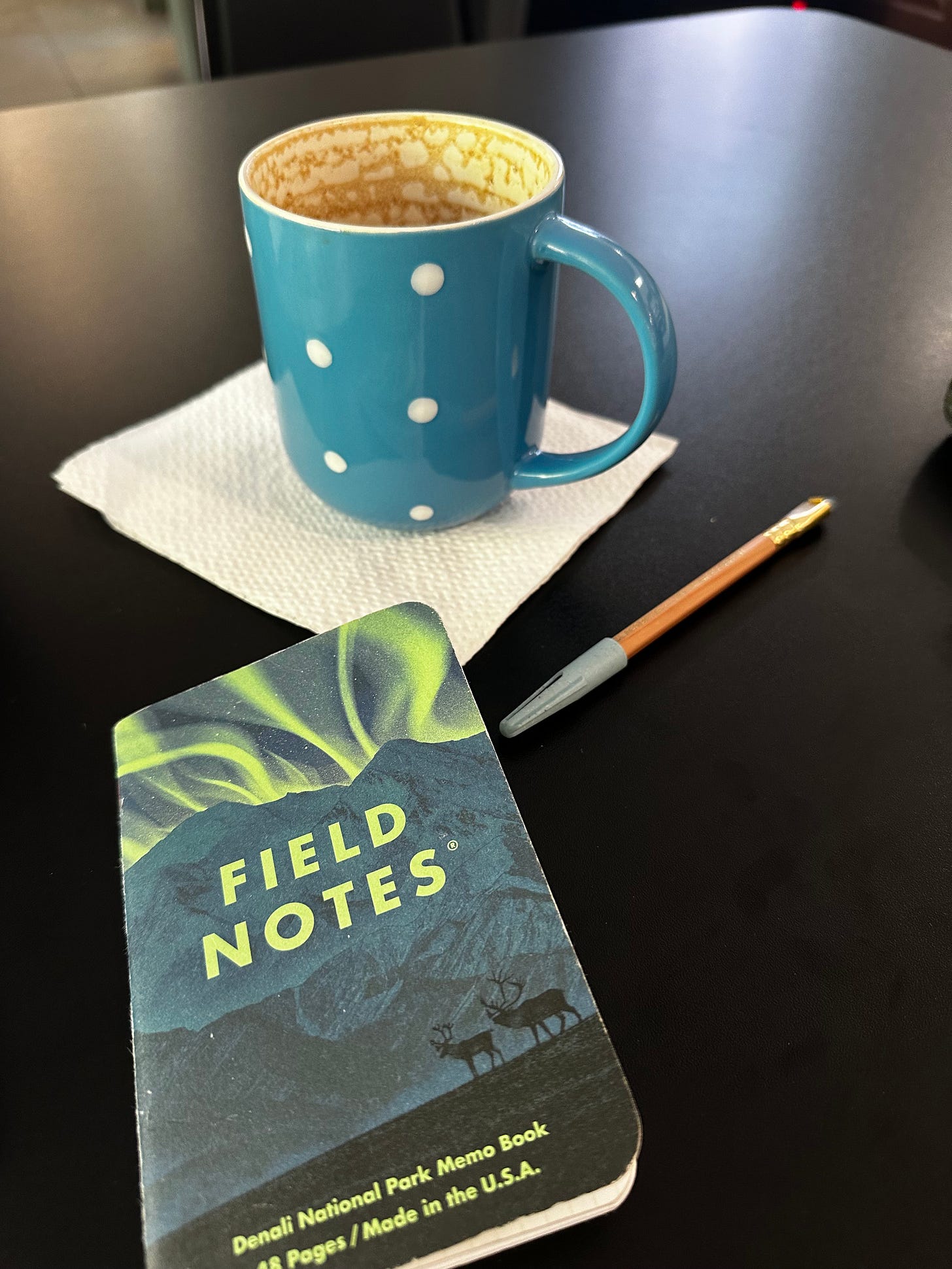

The pocket notebooks that I use most of the time are made by a little company in Chicago called “Field Notes.” They make beautiful, functional little notebooks, and I’m a bit obsessed with them. On the back cover of each of their notebooks, you will find these words:

Inspired by the vanishing subgenre of agricultural memo books, ornate pocket ledgers, and the simple, unassuming beauty of a well-crafted grocery list, the Draplin Design Co, Portland, Ore.—in conjunction with Coudal Partners, Chicago, Ill.—brings you “FIELD NOTES” in hopes of offering “An honest memo book worth fillin’ up with GOOD INFORMATION.”

In addition to their basic notebooks, they also offer a subscription to their quarterly limited editions. Needless to say, I am a loyal subscriber. (This post is not sponsored; I’m just a happy customer.) You can find cheaper notebooks, but you won’t find any that inspire such devotion. I occasionally will use another kind of pocket notebook, but returning to a Field Notes always feels like coming home.

I also have a desk notebook for longer writing sessions, the sort of A5 that I have used for decades. Otherwise, I would go through at least a couple of Field Notes each week.

If you are interested in the history of the humble notebook, I highly recommend Roland Allen’s excellent The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper, just published last year.

Let me know how you use your notebooks. Or are you entirely digital these days? (No judgment either way: whatever works for you!)

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet notebook to yours.

I keep a Field Notes book in my bag but rarely use it. Occasionally I remember to input the thought into Notes on my iPhone, but often times the thought just floats free into the ether, never to be recalled. For tracking what I read, I use a site/app called StoryGraph either on my phone or browser. I have a Rhodia notebook waiting to be started - I filled the last one with notes related to writing when I was taking a class, but I haven't done that for a while. Before bed, I jot down a few lines about the day in a five year journal that I started in January. I've only missed a few days and I think it will be really neat if I can keep it up over the span of five years. Lately, though, I have gotten really into sending snail mail - I think it's a justification to use fountain pens and nice paper and also another way to spend analog time.

I would dump my Apple Watch but I do need the sleep tracking for medical reasons. I suppose I could wear it just at night. I also have a little widget called a Brick that I can use to block apps on my phone when I notice I'm doomscrolling too much. The genius of it is that you can't unlock it without getting the little widget. Mine is stuck to the fridge so if I'm sitting on the sofa and by habit tap into Instagram but get the blocked notification I have to weigh whether it's worth getting off my butt.

I love my Maker Notebook which I have always modified to suit my particular needs. I have a post that features it here: https://zinagomezliss.substack.com/p/undrowning?utm_source=publication-search

Everyone marvels at the beauty — I made my notes pretty so I will want to look at my to do list again rather than weep and shut the book for the rest of the day.

I love your watch. My son has something similar. I have an Apple watch and at times it is a distraction (especially —horror— at church) however it has saved me in getting urgent phone calls and messages. I have such a health-complex family that it has been so important that people get in contact with me right away. I think otherwise I would be one of those mothers with a pager on me all the time — remember those? I think most people don’t need that level of connectedness though.