Not Back to the Future, but Forward to the Past

An introduction to this fall’s Classroom Journal (part 2), and the Stack of the Week (new feature!)

When last I left you, dear reader, I was in the midst of a quandary. With the beginning of term only a few days away, I was still without an organizing principle for my English Literature survey course. I could have taken the easy road and just dusted off an old syllabus, but I was determined to try something radically different this time, something that would overturn the traditional march through the years from the Middle Ages to 1800.

I had already decided to challenge that tradition by beginning at the end of the period—or, rather, beyond the end of the period with Jane Austen’s Emma, which dates from 1816. I made this decision because students are mostly familiar with the narrative and literary conventions of the novel as a form (even if they don’t yet recognize them as such), and so Emma would give us a baseline. If a text does not behave like a novel, then what are the differences? What are the implications of these difference for the intended audience, cultural context, aesthetic values, etc.? In order to ask these valuable questions, we have to establish the familiar conventions of the novel as a sort of “control group.” And Emma is the perfect choice to set these standards because Austen essentially invented many of these conventions and deployed them as deftly as anyone ever has.

But once you have established this beginning, where do you go from there? Do you press rewind and jolt us back to the beginning of the chronology marked by the course description, say, to Beowulf? It’s hard to imagine a text more radically different from Emma. But perhaps the differences are so great as to make them essentially incomparable, at least to start with. The shift would be disorienting, like shifting from Mozart to Metallica, or from Succession to Sophocles. Actually, that last one may not be such a big shift—I’ll stick with Mozart to Metallica.

Imagine going from this . . .

To this . . .

Both awesome! But too big a shift? It’s sort of difficult to compare the two.

What if, instead of making the big leap backwards and then going forwards again, a sort of pedagogical version of Back to the Future, we find a text from the century before Austen’s novel—perhaps a narrative that is not itself a novel but that is from a cultural space not quite so radically different as Beowulf would be? We can still use Doc’s DeLorean, but let’s take it back, say, a few decades rather than a few centuries—let’s take it “forward to the past.” So instead of going from Emma to Beowulf, what if we went from Emma to Gulliver’s Travels, and then from Gulliver’s Travels to Paradise Lost, etc. What if we took the whole semester chronologically backwards?

Stay with me for a minute. Gulliver’s Travels, like Emma, is a prose narrative, but it is different from Emma formally (it’s not a novel in the modern sense of the word), as well as tonally and thematically. This gives us a chance to consider these differences and their implications for intended readerships, ideas of gender and domesticity, and literary techniques. Swift uses first person, while Austen uses third person with generous dollops of free-indirect discourse. They both use irony and satire but in radically different ways. What are the effects of these differences? How do the two texts differ in terms of in characterological interiority? In terms of cultural commentary? How are these differing approaches expressed?

After that, let’s go from Gulliver’s Travels (eighteenth century) to Paradise Lost (second half of the seventeenth century). Now we move from narrative prose to narrative poetry. Why? Why does Swift choose prose and Milton verse?

To the modern reader, Austen is more accessible than Swift, who is more accessible than Milton. With each step along the way, we stop to ask why this is the case.

Then, let’s go from Paradise Lost to Twelfth Night—from epic to drama, going back about sixty years.

You see the pattern. With each step backwards, the territory becomes a bit less familiar, a bit more difficult. (OK, I admit, you could argue that Paradise Lost is more difficult than Twelfth Night even though it’s later, but let’s not split hairs.)

We can do the same with non-narrative forms. For example, while we are reading Emma we can also read some of Wordsworth’s poetry. Wordsworth’s poetic mode is still quite familiar to us in our time. But then, when we go backwards to the eighteenth-century poets, like Gray and Pope, we can see what Wordsworth is reacting against. We can see how different the aesthetics of eighteenth-century poetry were from Wordsworth’s, and from our own. Then we can go back to the previous century, to the poems of John Donne and Ben Jonson and Mary Wroth. With each step back, we have a baseline against which we can compare the unfamiliar aspects of the older poems. We can also see how the narrative and non-narrative texts talk to each other. (This can work to great effect, for example, when we look at Twelfth Night next to Shakespeare’s own sonnets.)

Now we’re cooking with gas.

We are not trying to cover everything. We are not trying to march through history chronologically, one damned thing after another. Instead, we are building with each step on what we know, on the familiar. This is analogous to how the study of mathematics works: you begin with more familiar operations (algebra, geometry) and then move to the less familiar, perhaps the less intuitive (trigonometry, calculus), and so forth. The analogy isn’t perfect, because in literature we are not necessarily moving towards more complexity as we move backwards through time, but simply towards less familiar territory.

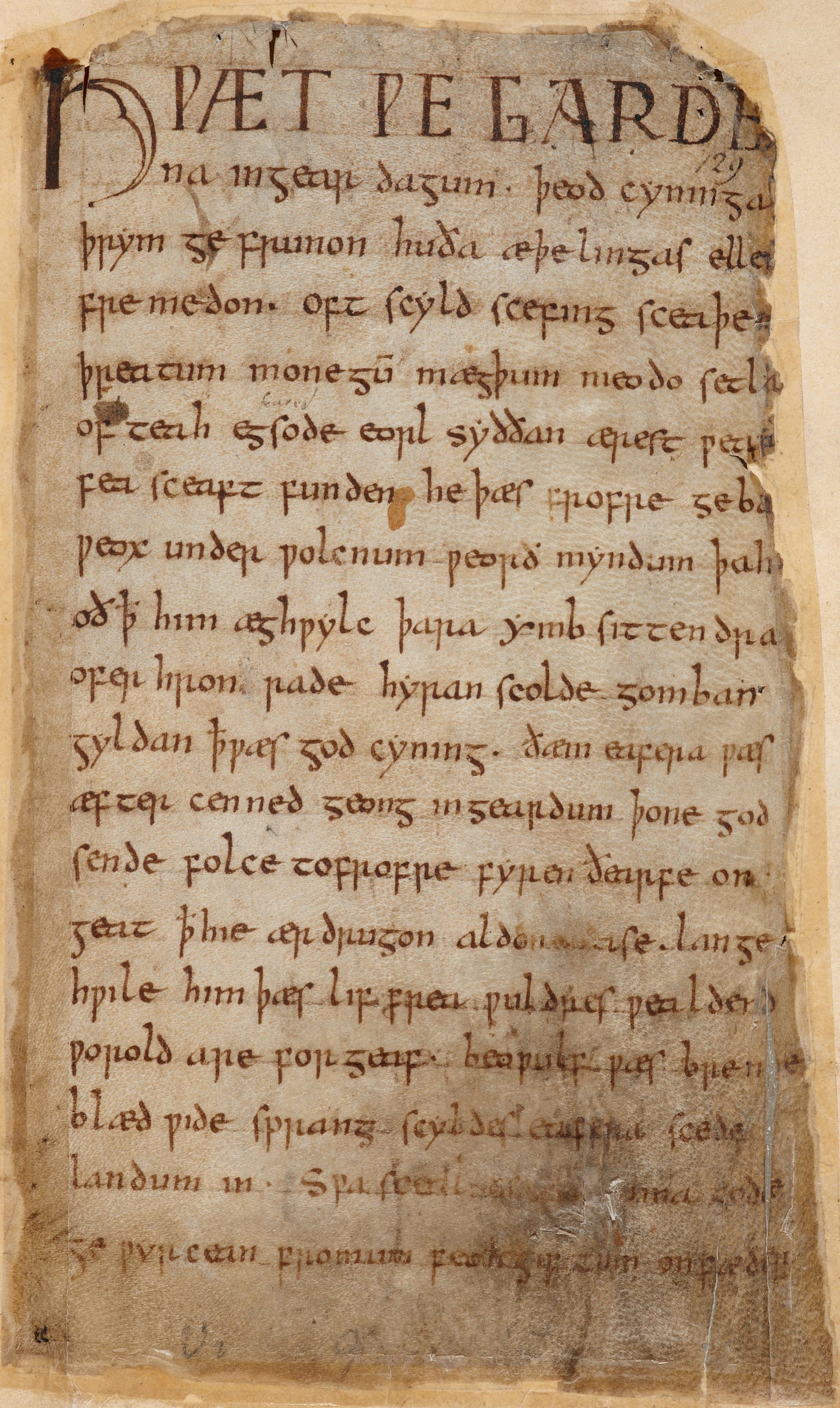

When we finally do make it back to Beowulf, our final text of the term, we have reached alien lands indeed. The poem begins:

Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum,

þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

In Seamus Heaney’s translation:

So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by

And the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness.

We have heard of those princes’ heroic campaigns.

Obviously, this is unfamiliar language. The “we” in the first line of the original (the third line of the translation) obviously does not include us as twenty-first-century readers. We probably have not heard of these Spear-Danes. We have no idea. Even the language itself is alien. We have reached a very unfamiliar place, but we have gotten here iteratively, and the poem perhaps seems less intimidating than it would have been if we had started here in week one of the semester. We are now seasoned readers of the progressively unfamiliar. As things get curiouser and curiouser (to paraphrase Alice), we remain curious. We have surmounted the challenges of Milton, Shakespeare, Chaucer, etc., and now we are ready for the radically alien aesthetic of Old English poetry.

So, this is the kind of anti-chronological movement that you can expect from this fall’s Classroom Journal of the English literature survey course. If you want to read along, start with Austen’s Emma. But just read it the regular way, front to back. Don’t try reading it backwards. I’ll see you in class.

However, dear reader, the survey is not the only course that will be featured in the Classroom Journal this semester. In the next regular post this weekend, I will introduce you to my course on literary criticism. Unlike the survey, this course is for English majors. It’s one of my favorite courses to teach, for reasons that I will explain.

Stack of the Week: Homo Vitruvius by A. Jay Adler

Today I'm starting a new weekly feature, the Stack of the Week, where I will recommend another publication on Substack (or elsewhere; I'm not married to this platform) that I have been enjoying. I will tend to focus on smaller newsletters that deserve more readers. (Heather Cox Richardson and Dan Rather, as great as they are, do not need my help, though I could use theirs. Heather? Dan? Are you listening?)

For the inaugural Stack of the Week, I draw your attention to the always interesting Homo Vitruvius by A. Jay Adler. Here is his description of the newsletter: "A writer's renascent light against the darkness, shined through culture, literature, and ideas." As you can see, in spirit his work is aligned with my own.

A good place to start reading is his pinned post, "A Portrait of the Artist from a Young Sentence," in which he charts his history as a writer and explains why he continues to write:

I’m not talking about “getting my feelings out” on paper. Writing isn’t therapy. I go to therapy for therapy. I’ve done that plenty. By purpose I don’t mean higher purpose, delivered from any higher source, or of value because it serves some higher end. I mean my purpose, and fulfilling it.

That’s it for today. I’ll send out my new weekly roundup of reading and listening for paid subscribers on Friday, and I’ll have something fresh for everyone on Sunday.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

I love this, and not just because I make a guest appearance at the end. :) I think immediately of works that have employed this approach, of working backward in time, to great effect. Pinter's *Betrayal*, probably his most accessible play, achieves real power. Less consistently, when it works, which I 've seen it do, Sondheim's *Merrily We Roll Along* does the same. And when you think about it, surveying English literature like this replicates the whole human knowledge project of digging ever deeper into the soil or penetrating farther backwards in space and time. And the way you explain the gradual increases in understanding from smaller scale contrasts makes perfect sense. I'm eager to follow along and read your reports. And thank you for that kind recommendation. Your stack of the week is a generous idea. I'll have to find a way to replicate it without simply copying youI

Maria Dahvana Headley has a very fun translation of Beowulf. She translates that opening “hwaet!” to “bro!”

But the whole thing is redolent with the heroics of the original, the alliterations and rhythms, and it’s pretty fantastic overall.