Why “Personal Canon Formation”?

A revisit—with a voiceover that includes the sounds of a dog chewing a toy

Dear Readers,

It’s just over three months since Personal Canon Formation launched, and readership and engagement have grown far beyond my expectations. This newsletter is now read across 25 US states and 18 countries around the world. Thank you all for reading; I feel honored that you choose to subscribe when there are a million things out there begging for you attention.

Today, instead of posting a new piece, I’m reposting the first-ever piece that I published here. When it dropped originally, I had three subscribers, and so I’m betting that many of you haven’t read it. I am going to begin re-upping some of these early posts once a month, and I’m going to add a voiceover to each.

Speaking of voiceovers, one of you who has to spend a lot of time in the car has told me that this feature would be very helpful, so I’m going to go back gradually through the archive and start adding audio. I’ll start with the more essayistic pieces. Anything for you readers! (Well, almost anything: I’m not going to learn to edit audio or try to cut out the various dog noises and mistakes.)

So this is how it all began. Enjoy.

Yours,

John

Personal Canon Formation (abstract noun): the process of discovering, interacting with, responding to, and assimilating into one’s consciousness works of art and other cultural artifacts of merit. The process is deliberate and thoughtful without being rigid or dogmatic; its results may be shared generously but not authoritatively. At its best it should cultivate honest, responsible criticism that does not shy away from passion even as it is meticulously analytical. It should promote stimulating conversation and debate without acrimony. It should broaden horizons and encourage empathy. It should enrich life without anxiety, without the dreaded FOMO. Finally, it should encourage actual freedom of thought and aesthetic experience rather than the apparent freedom of the endless “choice” that the algorithmic machine feeds us.

When Spotify first arrived on American shores, I thought that it was my childhood dream come true: the eternal jukebox. I grew up in the 80s and went to college in the late 80s and early 90s. I started out as a music major (before switching to English—a wise choice for me), and I wanted to listen to everything but had no money. What little money I had I spent on CDs (and books), but I could afford precious few. I spent countless hours in the listening room at the music library, which, thankfully, was one of the best in the country (at UNC-Chapel Hill), in order to listen to things that I couldn’t afford—most notably, recordings of Mahler’s symphonies, which were expensive because of their formidable length. I had posters of Leonard Bernstein and David Bowie on the wall of my dorm room. My music was my music, and no pop chart or radio station could dictate to me what I should like. I discovered Philip Glass and Billie Holiday and Ralph Vaughan Williams. I read voraciously about these discoveries. I wrote papers about them.

Fast forward a couple of decades: when Spotify arrived, I thought of how brilliant it would have been to have such a tool when I was younger. I could have listened to multiple recordings of Mahler’s Third Symphony, or David Bowie’s strange early records, or Sun Ra’s wonderfully weird discography. But after a few months with the platform, a strange, counterintuitive reality set in: all of this choice was not necessarily a good thing, or at least I was ambivalent about it. Of course, there was the well-attested problem that Spotify paid artists next to nothing for their recordings. But this was an ethical issue rather than an aesthetic one. There was also the issue of sound quality: my old CDs and LPs sounded much better than Spotify’s compressed files.

Spotify was betting that most listeners would choose convenience and availability over quality and deep engagement. Their algorithm would feed listeners what they “liked” with little or no effort required. They were right, of course. For most listeners this was fine: a steady stream of inoffensive background noise to accompany the endless scrolling that the algorithms of other platforms were providing.

To me, the whole experience was deeply unsatisfying, but it took a while for me to figure out why: it was too easy. When I visited the music library in college to use the listening room, it required deliberate effort. As a result, I valued the aesthetic experience: I listened closely; I took notes. Sometimes, if it was an especially powerful recording (the Argerich/Abbado recording of Ravel’s G-Major Piano concerto, for example, or Sonny Rollins’s Saxophone Colossus), I would save up my pennies and buy it. Then it became part of my personal canon.

This process was not conscious, nor was it unique. I knew many people who had their carefully cultivated personal canons, though they didn’t call them that. We all treasured our record collections and our libraries, and we laboriously moved them from apartment to apartment through our 20s, packing them carefully and treating them like so many heirlooms. Our personal canons fed each other, as we exchanged books and music and ideas. And this is simply what people did before the internet when they were interested in a deep engagement with culture.

The effortlessness of media access now is a blessing in many ways, of course, but we have also lost something. For one thing, we have lost the anticipation and piqued interest and eventual excitement of discovery. For example, I remember reading an ecstatic review of Robyn Hitchcock’s Globe of Frogs album some time in 1988. None of my local record stores had it in stock, and in those days a special order could take weeks, if it was possible at all. I couldn’t wait to hear this record. It turned out not to be a favorite album (not even a favorite Robyn Hitchcock album), and it did not become an entry in my personal canon, but that was part of the engagement. There were hits and misses. Paying fifteen precious dollars for something you didn’t know that you would like was something of an aesthetic gamble, but when you hit the jackpot, there was nothing better. I picked up Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins in the fall of 1990, simply because I went to an event on campus in his honor after his death. (Percy had been a UNC alum.) I had never heard of him. I read the novel in about two days, read the rest of his novels in the next few weeks, and ended up writing my MA thesis about him.

This kind of serendipity still happens, and it might even happen more often, but since the culture which used come out of the tap in your kitchen now resembles Niagara Falls, it requires conscious effort to fill your glass deliberately rather than having it smashed to bits by the force of the stream.

This is why, for me anyway, a concept like Personal Canon Formation (PCF) is necessary. Let’s use our technological tools carefully and consciously to cultivate our personal canons. Let’s focus more closely on what we read and listen to, even if that means missing out on the next big thing (or the next hundred biggest things). Let’s share our canons with each other generously and humbly, without judgment. Let’s talk about it.

These are the aims of this little publication. We want to create a space for this kind of aesthetic engagement. There will be hits and misses, but we can reclaim ownership of our aesthetic attention together. New posts Sundays and Wednesdays—with the weekly roundup for paid subscribers on Fridays.

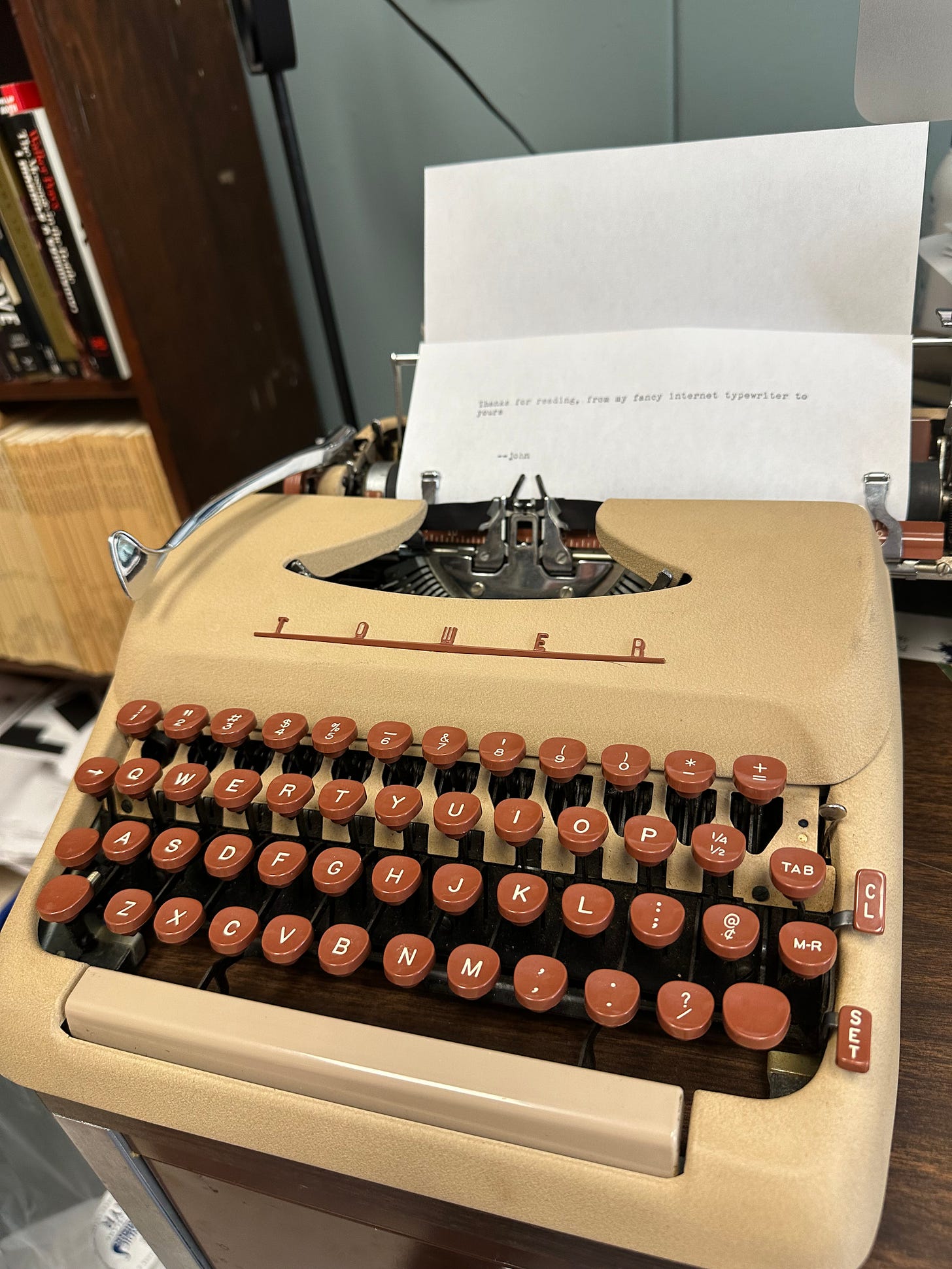

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

You have a lovely selection of books on your shelf. I would be quite happy in your library. One exception—Hardy. I read Jude the Obscure and was so sickened I could read nothing more.

We love things more deeply when and if we have to work for them. Thank you for the reminder.