In Sunday’s post, we considered the album’s spiritual search in the context of material desire and consumption, most clearly articulated in the title track’s pleading question: “Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?” Today, we explore the possible answers to the question offered up by side two. (If you haven’t read part 1, you can find it here.)

“Somebody Up There Likes Me”

The opener to side two at first listen seems to be a straightforward gospel song, but it could also be the sequel to “Starman” from Ziggy Stardust, as the “somebody” of the title could, if we judge by the lyrics, just as easily be a pop star from the sky (or perhaps the divine muse of the pop star) as Jesus. The opening statement that he is “everybody’s token on everybody’s wall” could refer to a concert poster or to a crucifix, and the interchangeability is precisely the point. The “somebody” here is the salvational possibility of American music, in this case in the guise of the iconic star that the album’s title track yearns for, and he occupies the same position as the “Starman waiting in the sky”—a cult of personality that “smiles on the whole human race.” This possibility represents the first of a series of responses on side two to the spiritual and sexual frustrations expressed on side one. This first response is exuberant musically, with Bowie’s encomium to this nameless divinity echoed by the gospel-inflected backing vocals repeating “somebody, somebody” and “somebody up there.” In a typical gospel tune, these backing vocals would be calling out Jesus’s name and offering him praise; their replacing this specificity with the anonymous “somebody” highlights the song’s central ambiguity. This ambiguity haunts the song’s central moment of apparent self-affirmation: “His every loving face / Smiles on the whole human race, / He says I’m somebody.” That last line could be an expression of the central promise of pop music to the alienated: the music tells me that I’m somebody, even if I’m alone in my room, listening to records and genuflecting before my pop icons. But the line could also read “He says, ‘I’m somebody,’”—a declaration of his own authority, of his own entitlement to adoration—which would suggest the narcissism of the pop star and the possibility that such quasi-worship feeds destructive tendencies as well. Feed my ego, and I’ll be your savior.

This idolizing of the famous connects thematically to the closing track of the album, “Fame,” in which the voracious ego has become a destructive trap, and this thematic connection creates a trajectory from gospel exuberance to darkly funky pain. In “Somebody Up There Likes Me” the pop star (or the actor) seems to be a viable, indeed preferable, alternative to political leaders, as the song dismisses the latter as transitory and lacking the power of stardom: “Tell me can they hold you under the spell / Or can they walk and hold you as well / As a smile like Valentino?” But of course, this spell is perhaps more likely to be destructive than salvational, as the following line suggests: “Could he sell you anything?”

“Across the Universe”

John Lennon’s presence in the studio was likely a motivating factor for this performance. The Gouster does not include the song, and it’s a break from most of the rest of the album stylistically and thematically. Indeed, considering the brilliance of the three songs from The Gouster that were left off of Young Americans, the inclusion of this somewhat eccentric Beatles cover is surprising. Many critics would argue that it is the album’s low point. It is, however, a bold interpretation of the Beatles classic, as Bowie’s vocal is dramatically pleading, which is radically different from Lennon’s laconic, dreamy vocal on the original recording.

The song’s inclusion on the album makes a bit more sense when it is considered in the context of the spiritually searching qualities of some of the other songs, particularly “Somebody Up There Likes Me” and “Can You Hear Me,” which precede and follow it, respectively, in the running order. According to Nicholas Pegg’s brilliant The Complete David Bowie, in a 1997 interview, Bowie singled it out as a favorite Beatles song and suggested that it represented Lennon’s spiritual confusion and moral aspiration, which seems to be an insightful assessment. The lyrics of the song suggest a surrendering of the ego to a range of stimulations, emotions, and ideas, and Lennon’s original performance embodies this giving up of the self. Bowie’s performance, on the other hand, seems in some sense to convey a desperate desire for self-surrender even as it asserts the centrality of the self through this very desire. “Nothing’s going to change my world” sounds here like a protest rather than a mantra. Despite the general critical distaste for this track, to my ears, Bowie imbues it with a heartfelt drama of contradiction that is absent from the original; the song becomes a struggle rather than a surrender. Anything other than this kind of assertion of desire would be drastically out of place on this album. As it stands, it leads nicely into the torch song that follows.

“Can You Hear Me?”

This song works as a kind of response to the call of “Right” to take “it all the right way”: “Show your love, love / Take it in right.” It seems at first listen to work as a standard, soul-inflected love song, but in the context of the album and of Bowie’s career as a whole, it takes on other resonances. The most curious line in the song follows directly upon a lyrically typical (for a pop song) memory of heartache. Rather than an assurance of sincerity or singularity that we would expect after this (something like “you’re the only one, baby”), instead the lead vocal warns that “I’m checking you out one day to see if I’m faking it all.” The pronoun choice is odd: it should either be “I’m checking you out one day to see if you’re faking it all,” or “You’re checking me out one day to see if I’m faking it all.” However, this apparently scrambled syntax makes a kind of sense in the Bowie universe if we accept the idea that the speaker can judge himself only through the appraising eyes of others.

If we read it this way, then the song coheres with the manifestation of the egocentric pop star of “Somebody Up There Likes Me” that begins side two and the burned out shell of a self of “Fame” that closes it. It is inescapable to read this decentered ego in the context of the Diamond Dogs tour that was underway as Bowie was writing and recording this song; he sings: “Sixty new cities and what do I find?” As Bowie is judged nightly by crowds who have come to view the infamous spectacle of this tour, he writes a song that at once acknowledges the damage this inflicts on the sense of self and also asks the poignant question: “Can you hear me?” We have returned to the plea of the album’s opening track: a search for a kind of salvation in a personal universe that has discarded both the vocabulary for it and the capacity for believing anything beyond that trappings of fame and detritus of disposable culture that the singer is trying to escape. In the next song, and the bleak conclusion to the album, these trappings are in the process of destroying him: the consumer is being consumed by consumption.

“Fame”

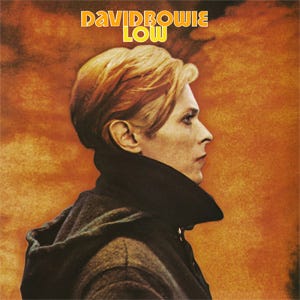

It is, of course, ironic that Bowie’s breakout hit in America, the song that secured his fame, is a bleak assessment of the personal damage inflicted by the very state of fame. It is the presence of this song, even more than the absence of “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)” or “Who Can I Be Now?” that transforms the album from the slick Gouster dance record to the searching, troubling Young Americans. Despite its irresistible funk foundation, it’s a song as bleak as anything on Station to Station or Low. Furthermore, it doesn’t disguise the bleakness; a bare perusal of the lyric sheet reveals lines whose bald pessimism defies further analysis: “Fame - what you like is in the limo, / Fame - what you get is no tomorrow, / Fame - what you need you have to borrow.” The autobiographical aspects of these lines are all too apparent, considering that Bowie had only recently discovered that he had been practically bankrupted by the greedy and deceptive practices of his manager. Bowie was, indeed, living on credit. It’s also difficult to hear the song after 1980 without being haunted by John Lennon’s falsetto backing vocal repeating the song’s title: no tomorrow, indeed. If Bowie was a potential casualty of fame in early 1975, Lennon would become a literal one not quite six years later.

Perhaps most devastating is its placement as the album’s concluding track, as the ultimate answer to the pleading if hopeful question of the album’s opener: “Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?” Well, maybe, but the tears won’t save you for long, nor will the song. All you can hope for is a “rain check on pain”—not salvation, but rather an opportunity to put off the dark reckoning that is surely coming.

What would follow this darkness? Arguably, a retreat from fame: Station to Station, Low, Heroes, and Lodger, the four albums that closed out the 1970s, are defiantly experimental and were certainly alarming to executives at Bowie’s record label, who were hoping to build on the success of “Fame,” despite the fact that these albums would prove themselves to be ahead of their time and tremendously influential. Personally, however, it would prove to be a nadir for Bowie, as he almost became a casualty to drug addiction and paranoia, to fame. A critical view of the artist’s trajectory might view Young Americans as a transitional record, between the glam period of the first half of the decade and the experiments of second half. It is more than this, however. It is one of the most clear-eyed assessments in pop music of capitalist materialism and its crushing effects on the soul.