I have always had trouble reading fiction on a screen—any narrative really. It probably goes back to something quite primal, to my first childhood encounters with fiction, immersing myself in narrative with the help of this amazing physical object called a book. I had no electronic devices in my bedroom in the late 1970s and early 1980s, or at least nothing more complicated than a record player. But I was happy to spend hours there, as long as I had my books (and records).

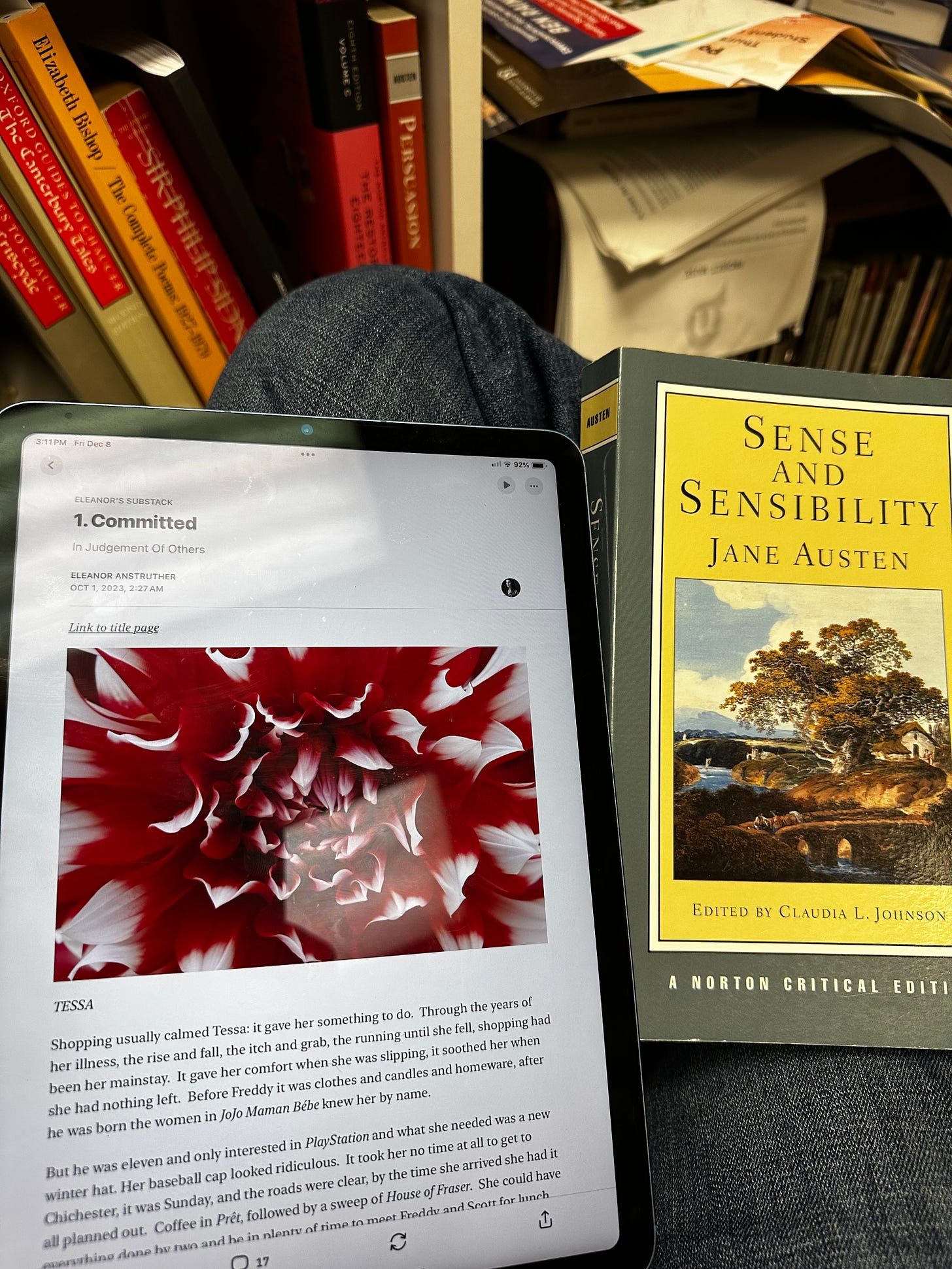

I have seen the studies that suggest that we retain more when we read on paper, and there are the obvious distractions of notifications and apps on computers and tablets. But I think that the preference for me is essentially an aesthetic one: a book is a beautiful and pleasing artifact, pleasant to hold and carry, and not just the fancy expensive ones, but even the cheap, well-worn paperbacks. I have a Kindle, but I rarely use it, though I have read ebooks in a pinch—when I needed to get a hold of a novel quickly for a book club meeting, for example. When I do read on a screen, I have found that I prefer the iPad over a Kindle or a laptop, and I think that this also comes down to an aesthetic choice. I know that the Kindle was designed as a kind of book-replacement, but the iPad is a more pleasing aesthetic object, and, therefore, I prefer it.

Of course, another advantage of the iPad is that I can read Substack on it, which can, of course, be an immersive experience. I must admit, however, that I have been slow to start reading fiction on Substack, and I think that, again, it comes down to that ingrained sense that fiction comes in book form.

A few months ago, however, I discovered Mary Tabor’s magnificent memoir, (Re)making Love, which she has been serializing on her Substack,

. While it’s not fiction, it is an extended narrative, and for the first time on this platform, I found myself totally immersed for an extended reading session, and it was just like getting lost in a traditional book. I started reading from the first chapter and didn’t stop until I had reached the most recent installment. (Only Connect was the Stack of the Week back in September: see this post.)This happened to me again last Thursday evening, this time with a piece of fiction, which is being serialized on Substack. At the moment, it’s difficult for me to become immersed in anything, because it’s the time of the semester when I have to divide my attention among a million bits of text that I must read every day—books, articles, student papers, emails, my university’s LMS, etc., etc. But when I started reading, I couldn’t stop, and I refused to be interrupted. I was reading on my iPad, and it didn’t matter that the text was not on paper: the immersion was that complete.

That piece of fiction is

’s novel, In Judgement of Others, and the Stack of the Week is the simply but aptly titled Eleanor’s Substack. Eleanor, as she explains on her “about” page, is “a novelist who felt like she was shouting into the void until Substack came along and filled me with connections to you, readers, the people who help on a daily basis to remind me I’m not alone.” Her first novel, A Perfect Explanation, was long-listed for the Booker prize in 2019. I have not read it, but it has moved right to the top of my TBR list. On Substack, she has serialized her memoir, 65 Postcards, and a follow-up, The Recovery Diaries. I discovered her publication when she was about halfway through the latter, and have been struck by her shaping of sentences, her psychological insight, and her ability to draw the reader in.I had been saving In Judgement of Others for when I had more time, but I sat down to read a couple of chapters of the novel so that I could say something about it here. And, of course, I read more than just a couple of chapters, and I’m now anxiously awaiting the next installment. It is astonishingly good. From her own description: “Set in a neat market town in southeast England, it’s a dark comedy about psychosis in the Home Counties.” Read the first chapter, and you won’t want to stop:

I’m now going back to read 65 Postcards, and I’ll likely read straight through that too. Eleanor’s writing makes me feel good about the future of fiction, and I think that it will look reassuringly like the past: in our world of push notifications, TikTok, and shortened attention spans, great writing will still have the power to immerse us, even if we’re busy, even if it is on a screen.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

John, I cannot begin to tell you what this means to me. I mean that literally. I just can't. I will come back to it when the serialisation is finished. Until then, thank you.

For a long time I use to read only physical books. Now I'm a convert to reading on my MacBook for two practical reasons: I can make the type big so I don't have to strain my aged and aging eyes and I can search a book for key words.

Thanks for the recommendation, John.