In last week’s post, we looked at Gulliver’s letter to his cousin Sympson, which formed part of the front matter to the 1735 edition of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Gulliver has succumbed to despair, is contemptuous of all humankind, including his family, and prefers the company of the two horses in his stable, or, as he calls them, “two degenerate Houyhnhnms.”

Though the letter is hilarious, it is also devastating—because it shows us the descent into madness of a man who, despite his flaws, initially appears to us as well-meaning and decent if unimaginative. It is devastating also because it seems to present a stark choice to the reader concerning how we should respond to human corruption and greed: shall we respond with innocent optimism (the early Gulliver) or with hopeless misanthropy (the post-Travels Gulliver)?

I suggested in the previous post that Swift may actually provide us with a possible third way, an alternative to these painful conclusions—but to arrive at this alternative, we first need to consider briefly Gulliver’s trajectory through the four parts of the book. (Actually, I won’t be discussing part three, as entertaining as it is, since I think that it is something of a digression from the main narrative.)

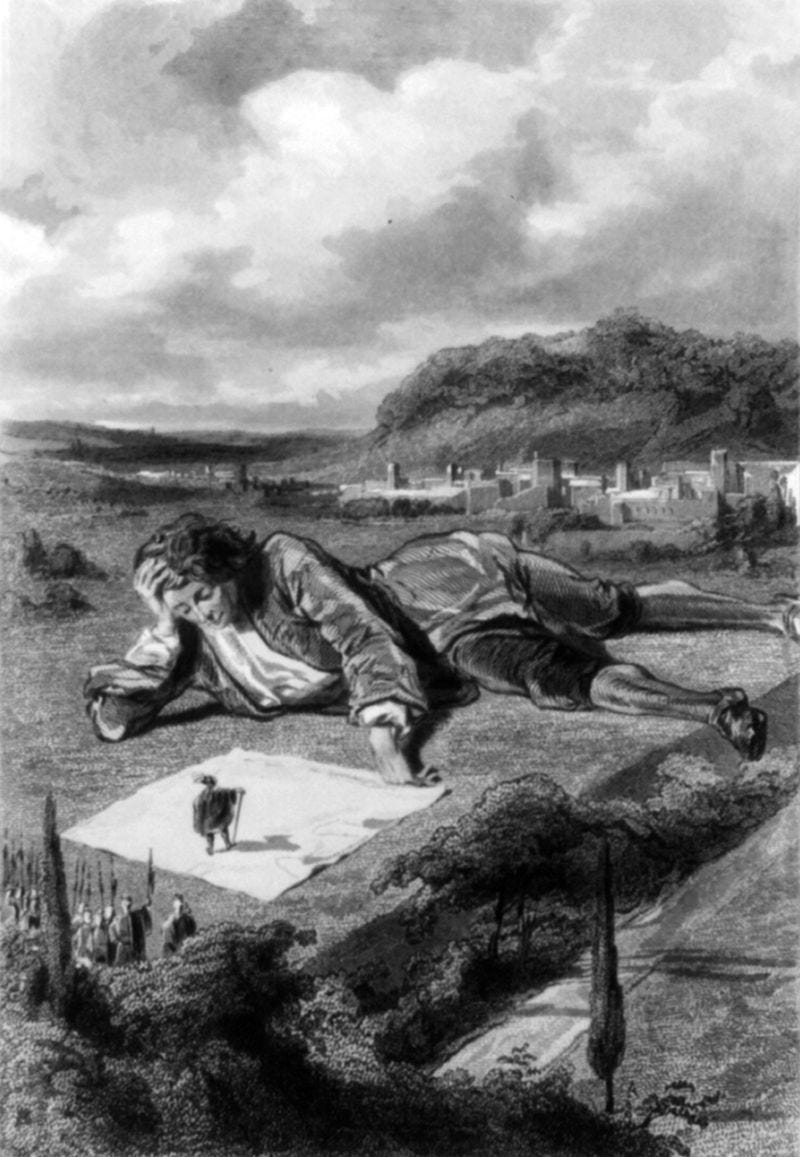

The first part takes Gulliver to Lilliput, the land of six-inch people whose pretensions and corruptions are inversely proportional to their body mass. Their tiny emperor, for example, is referred to in public documents like this:

. . . delight and terror of the universe, whose dominions extend five thousand blustrugs (about twelve miles in circumference) to the extremities of the globe; Monarch of all Monarchs; taller than the sons of men; whose feet press down to the center, and whose head strikes against the sun; at whose nod the princes of the earth shake their knees; pleasant as the spring, comfortable as the summer, fruitful as autumn, dreadful as winter.

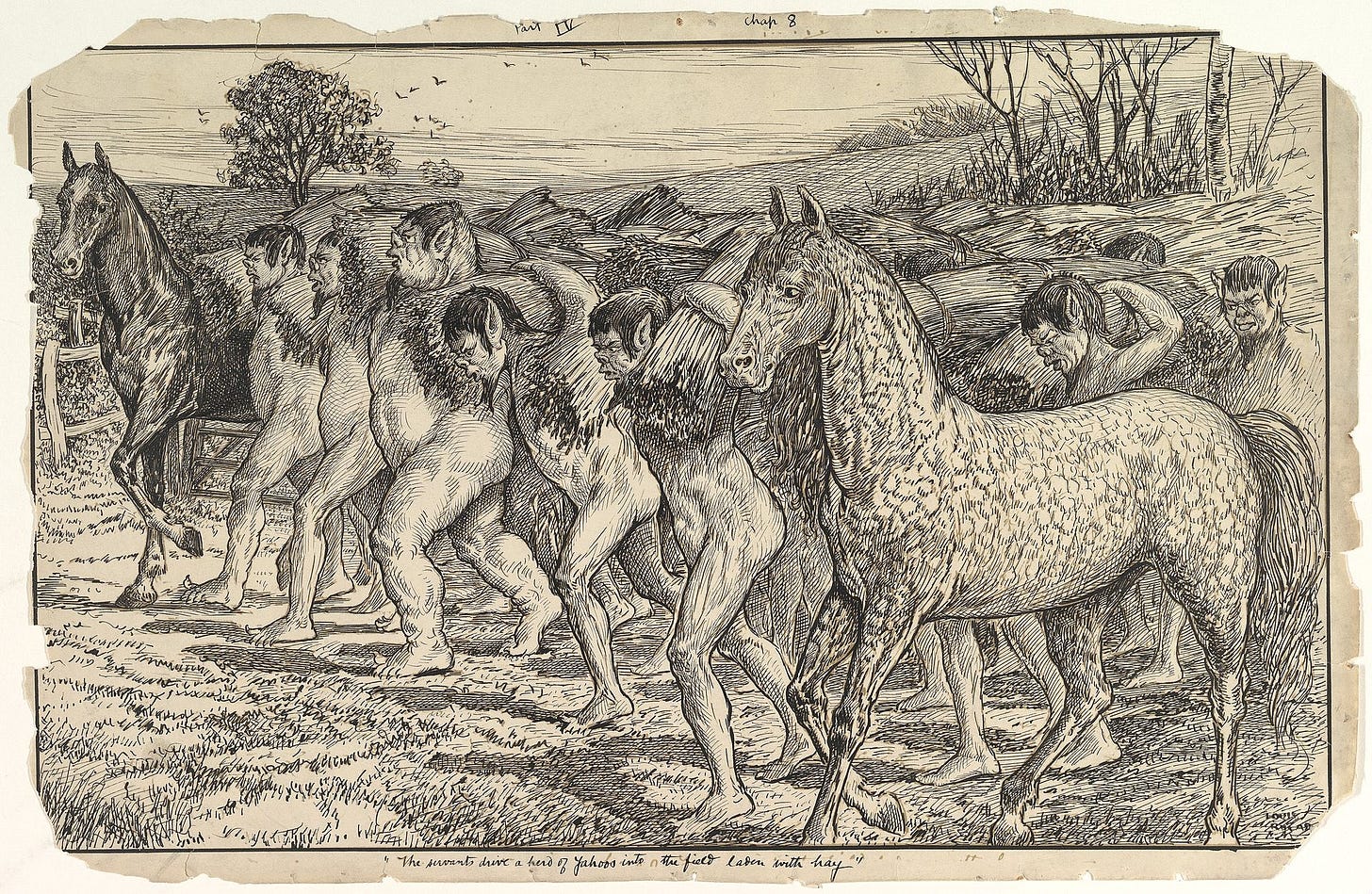

To this pencil-sized king, Gulliver regularly drops to his knees in supplication, so reverential is our hero to the trappings of power, despite his own relative massiveness. (See the picture above to form a mental image of such an encounter.) It is worth recalling that the development of the telescope and the microscope, in which Swift took great interest, had altered notions of perspective: in relation to the size of a biological cell, we seem very large, but in relation to the scope of the universe, we seem very small indeed. With these alterations in perspective, it is necessary for those in power to spin ever more forcefully their narratives and illusions of grandeur; hence the tiny emperor who styles himself as a giant. And Gulliver, like most people, is ready to accept institutional power as a fact despite any contrary evidence—so acclimated is he to socially constructed hierarchies.

Gulliver is charmed by the Lilliputians because they are too small for him to see their physical flaws, just as he is too innocent to notice their moral flaws until it is almost too late. He escapes after being warned of plans to blind him and then to use him as a giant slave.

The physical flaws of the Brobdingnagians in the second part of the book, on the other hand, are all too apparent to Gulliver. To these giants, Gulliver is the size of a Lilliputian, and he is, therefore, sensitive to their powerful body odor and disgusted by the enormous pores and pimples on their skin. Meanwhile, in Brobdingnag, he behaves like a Lilliputian—overly proud of his minuscule accomplishments (killing a rat with his sword, playing a tune on a giant keyboard). In a royal audience, after he boasts of English military accomplishments and explains European political customs (and corruptions), the king responds:

. . . by what I have gathered from your own relation, and the answers I have with much pains wringed and extorted from you, I cannot but conclude the bulk of your natives to be the most pernicious race of odious little vermin that nature ever suffered to crawl upon the face of the earth.

While Gulliver reacts defensively to this verdict in Brobdingnag, he reaches the same conclusion about humans himself during his sojourn with the Houyhnhnms in part four. If you have read the book, then you know that the Houyhnhnms are a race of apparently reasonable horses, capable of language and culture. However, the Houyhnhnms enslave creatures known as Yahoos, who are humans bereft of language and reason. During his time among them, Gulliver grows to admire the Houyhnhnms and to despise the Yahoos and, by extension, to despise himself.

There is a key point here that readers often miss because Swift doesn’t spell it out, though it is everywhere implicit: the Houyhnhnms, as animals, are incapable of comprehending abstraction. Because of this lack, they have no concepts of money, ambition, political power, or written language. This means also that they cannot lie (just as your dog or cat cannot lie), and they have no word for the concept. While this seems like a good thing, it is important to note that the most noble human accomplishments and values are rooted in our capability to comprehend the abstract. Yes, money, ambition, and political power are abstractions, but so are integrity, generosity, art, literature, love, peace, and humaneness.

While Gulliver, therefore, works to rid himself of human vice in the presence of the Houyhnhnms, he also loses his sense of the humane. This becomes apparent throughout part four, as his contempt for the Yahoos becomes more pronounced, to the point that when he constructs a boat (after being ultimately expelled by the Houyhnhnms because of his Yahoo status), he makes use of the skins of Yahoos without batting an eye: “My sail was likewise composed of the skins of the same animal; but I made use of the youngest I could get, the older being too tough and thick.” Yes, that’s right: he makes his sail out of the skins of children. Furthermore, he seals the boat with “Yahoo’s tallow,” or the rendered fat of humans.

It is in this state of insanity, self-loathing, and contempt for human beings that he once again encounters Europeans, and here is where, I think, Swift offers us his alternative to naïve idealism and to misanthropic despair.

The giveaway is in the use of one word: the Portuguese sailors who rescue him speak to him “with great humanity” (my italics, Gulliver’s word choice). The use of this word deconstructs Gulliver’s misanthropy: he obviously means this in a positive way. Humanity here means compassion, generosity, empathy. Despite Gulliver’s horrific, insane behavior towards them, the Portuguese, and especially their captain, Pedro de Mendez, treat him with patience and tolerance. They are humane. Their behavior and Gulliver’s use of the abstraction humanity are at odds with everything that he apparently believes to be human at this point in the narrative. Gulliver can’t stand the human smell of them and is disgusted when Don Pedro generously gives him fresh clothes: “This I would not be prevailed upon to accept, abhorring to cover myself with anything that had been on the back of a Yahoo.” (One might note here the irony that he has used the dried skins of Yahoos to fashion his shoes.)

When they arrive in Lisbon, Don Pedro offers Gulliver a place to stay, provides him with food and clothing, and gives him money for his voyage home, despite the fact that his guest remains terrified of all humans. When Gulliver says goodbye, Don Pedro “took kind leave of me, and embraced me at parting; which I bore as well as I could.”

Gulliver’s wife and family are also remarkably patient with him and continue to love him despite his contempt:

My wife and family received me with great surprise and joy, because they concluded me certainly dead; but I must freely confess, the sight of them filled me only with hatred, disgust, and contempt; and the more, by reflecting on the near alliance I had to them. For although since my unfortunate exile from Houyhnhnm country, I had compelled myself to tolerate the sight of Yahoos, and to converse with Don Pedro de Mendez; yet my memory and imaginations were perpetually filled with the virtues and ideas of those exalted Houyhnhnms. And when I began to consider that by copulating with one of the Yahoo species, I had become a parent of more, it struck me with the utmost shame, confusion, and horror.

As soon as I entered the house, my wife took me in her arms, and kissed me; at which, having not been used to the touch of that odious animal for so many years, I fell in a swoon for almost an hour.

After being home for five years, he finally begins “to permit my wife to sit at dinner with me, at the farthest end of a long table; and to answer (but with the utmost brevity) the few questions I ask her. Yet the smell of a Yahoo continuing very offensive, I always keep my nose well stopped with rue, lavender, or tobacco leaves.”

Juxtaposed against Gulliver’s misanthropy, then, we see humane behavior from Don Pedro and the Portuguese and from his own wife and family. They show him love and kindness; they take pity on him in spite of, or because of, his madness. This is Swift’s third way. This is our alternative both to unrealistic idealism and to the despair of self-loathing. The betterment of humanity happens with small, selfless acts of kindness, despite the bad behavior of others. Meanwhile, the ultimate object of Swift’s satire is the very misanthropy of which Swift himself was accused (and to which he admitted in a letter to his friend Alexander Pope), and to which Gulliver has fallen prey.

The ultimate example of the humane in Gulliver’s Travels is not to be found in the Houyhnhnms. They are, after all, not human at all. It is to be found in the kindness, the patience, the humanity, of Don Pedro de Mendez and Gulliver’s own wife.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Great read, yet again!

I would like to point out how Don Pedro is also an experienced, seafaring traveler that has experienced the world and all it has to offer, such as Gulliver himself, who should by all accounts succumb to his "yahoo" nature and benefit from Gulliver's plight as a stereotypical corsair. However, we find his immediate response is to embrace him, feed him, and shelter him back home rather than ransom him for selfish gain. This again reiterates your argument that even the institution that Gulliver willingly adheres and explains to the Houyhnhnms is not 100% accurate.

Also, I think Swift might be poking fun at the micro/macro perspective of the Enlightenment as well. At the tales resolution, Gulliver is looking down the wrong end of the telescope. He perceives humanity at a blurry distance that blobs us all together as a misshapen construct, or "yahoos," rather than seeing clearly the miniature acts of kindness magnified before him that separates humans from the "yahoos."

Gulliver's weak mind! Alas, he is all too familiar. But he reminds us of our call to be humane humans.

Thanks, Gull!