There is no precedent in English for what Chaucer does in his most famous work, The Canterbury Tales. There had been satire; there had been frame narratives; there had been collections of stories; but there was nothing remotely like this strange, funny, messy, unfinished, magnificent hodge-podge of genres, literary modes, and poetic forms.

So where did Chaucer get the idea? The answer to this question must be speculative and complex.

Let's start with what he does with his narrator. There had, of course, been first-person narrators before. Chaucer had used the first person in his dream visions, as we learned last week with our reading of The Book of the Duchess. There is a clear difference here, however: instead of an account of a dream, this purports to be an account of waking life, which, ironically, is a signal of self-conscious fictionality.

A clear model for this type of narrator is Dante. In The Divine Comedy, Dante presents us with a clear fiction that he narrates as if it were a personal experience. We all know that he didn't really meet up with Virgil and go on a sight-seeing tour of Hell, but he pretends as if he did. As readers of modern novels, this is not particularly surprising or strange to us. Novelists do this sort of thing all the time. But this was a radical literary innovation in the fourteenth century.

In The House of Fame, Chaucer had parodied aspects of Dante's narrative through his first-person avatar, but that had been in a dream vision. In The Canterbury Tales, our narrator insists that he is simply reporting what he saw and heard. Furthermore, he apologizes in case he gets it wrong, and for any potentially inoffensive material: he must report things accurately or else be dishonest. But, of course, he made it all up in the first place.

🙋♀️

At this point, attentive undergraduates will raise their hands and ask this question: does Chaucer use this device in order to avoid political trouble for anything controversial in his book? That's plausible, except that I really don't think that any intelligent reader of either Dante or Chaucer would have believed that this was anything but fiction, and Chaucer certainly knew this. It's possible, however, that ironic signaling of the text's fictionality would render it relatively harmless (for Chaucer, if not for Dante, who, after all, was writing in exile). You might think of Puck at the end of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream: don't be offended, good people; it's all fun and games.

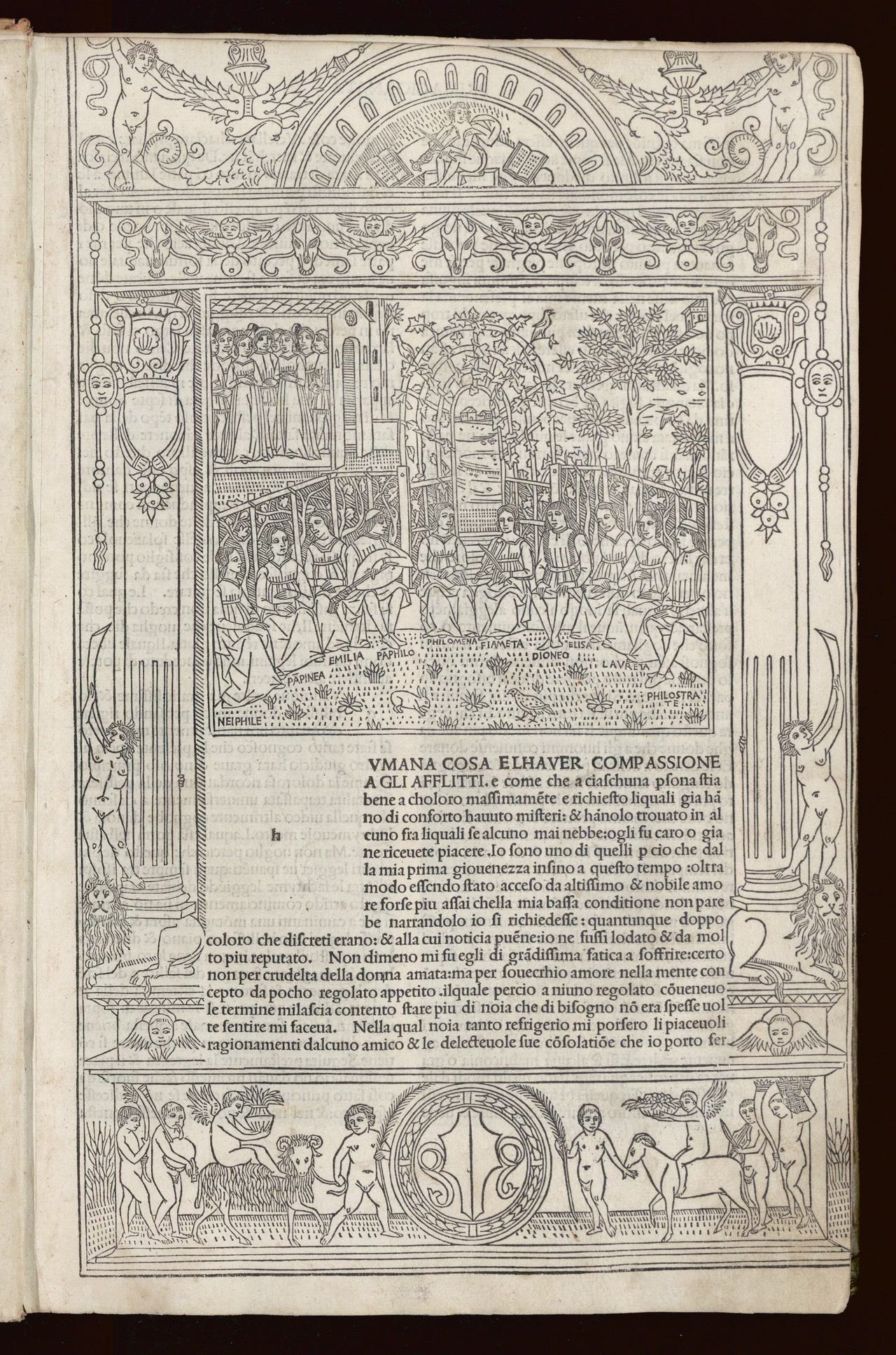

Another Italian writer who provided a different kind of literary model was Boccaccio, much of whose work Chaucer knew very well, because it had served as a source for some of his most important poems. Boccaccio was relatively unknown in England at the time, and so it is likely that Chaucer became acquainted with his work during his diplomatic missions to Italy, and he may have brought home manuscripts.

While Boccaccio is not a direct source for the Tales' narrative framing device, he may have provided something of a model in his Decameron, which is also a collection of stories with a framing narrative in which characters tell tales. In Boccaccio's frame, ten well-off Florentines retreat to the country to escape the Plague. To pass the time, they tell tales to each other. This seems a clear parallel to Chaucer's pilgrims telling tales to pass the time on the road to Canterbury.

Chaucer's innovation here, however, is in the tale-tellers themselves. Rather than characters from a single privileged class, he chooses them from across the social spectrum: "a compaignye / Of sondry folk, by aventure yfalle / In felaweshipe" (General Prologue, lines 24-26). Again, as modern readers of novels, this does not surprise us. However, the fact that Chaucer makes us read across social stations represents an extraordinary choice on his part. Here we have members of all three estates talking to each other and given more or less equal time to hold the floor, even if they don't always get along.

This innovation is made possible by the historical phenomenon of the pilgrimage itself, which was, as Chaucer tells us in the famous opening lines of the Tales, set in motion each year by the coming of spring and the desire to travel after a long, cold winter. (Look for much more about these opening lines in the next installment.) The great leveling device of medieval society, theoretically at least, was the sacrament of confession and the commonly accepted idea that we are all alike as sinners before the judgment and mercy of God. From contrition, comes confession and penance, which may lead to pilgrimage.

The leveling theory was limited, of course, since not all had the means or opportunity to travel, even a relatively short distance, and certainly not to more exotic pilgrimage destinations like Compostela, Rome, or Jerusalem. As Chaucer tells us, though, the most popular pilgrimage in England was to the shrine of St. Thomas Beckett at Canterbury, which would have been in reach of many more people than those distant sites. So the gathering at the Tabard Inn would have been plausible—that a range of people from different walks of life might make this a stop on the road to Canterbury.

Chaucer knew this road. In retirement, he moved to Kent and would have seen pilgrims come and go on their way to and from the shrine. He also, apparently, knew the Tabard Inn and its innkeeper, Harry Bailey—a real place and a real person. The Tabard was, indeed, in Southwerk, not far from the south bank of the Thames, outside London proper and on the way to the countryside.

This particular historical reality—the presence in the Tales of a real innkeeper—led many nineteenth-century scholars to comb the archives in search of friars named Hubert and Prioresses named Eglantine. Harry, however, seems to exist in this fictional space as a sort of toe-hold in the real world, as a marker of plausibility and common knowledge for the friends among whom Chaucer circulated installments of the Tales as he worked on them.

Chaucer would have been uniquely positioned for this social cross-section and this geographical crossroad. As we discussed in an earlier installment, having been raised by a mercantile family with court connections, he would have known people from all sorts of different social stations and occupations. These social realities, in combination with Chaucer’s wide reading and literary curiosity, made The Canterbury Tales possible.

In our next installment, we will look more closely at The General Prologue. Let me know if you have questions or comments about the famous opening of the Tales. For our first musical selection, try out this album of music by Machaut, Chaucer’s older French contemporary:

Medieval Music playlist on Apple Music

Medieval Music playlist on Spotify

We will discuss the specifics of this music in our next installment as well.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet inn to yours.

I am going to suggest that reading some in Middle English, in the original, with Chaucer is a good idea. It is a dialect of Middle English that is a great deal more like our own than others, especially Gawain in the Green Knight, and there are references that are used even to this day, for example, the April is alluded to in TS Eliot.

A few readers will be motivated to read all of it in Middle English, and all will see that there is a reason why Chaucer was the greatest Middle English poet in a world where even the literate had very little text to chew on because it was the era of copy rather than publish.

And every few years you will get a polyglot who understands that this is a dialect worth grabbing onto.

I am familiar with Dante, so I was able to make some connections with The Book of the Duchess, but I'm not familiar with Boccaccio at all. I'm finding that I'm not only reading Chaucer for the first time, but I'm also coming into contact for the first time with the authors/works that inspired him. Essentially learning a whole new language/world that I don't currently have much of a frame of reference for!

When you talked about the different classes of pilgrims all coming together, it reminded me of what Dr. McLaughlin said in class last week, about the "law of right order:" it was proper for the Knight to tell his tale first, but the others were surprised when the Miller volunteered to go next.