Dear Reader, I was running a fever on Monday night. I had body aches, chills, and hot flashes. I feared, in the midst of my misery, that I would have to delay this final Shakespearean installment yet again. But then Tuesday morning dawned, and, miraculously, I felt better—a bit of a residual cough and a stuffy nose were the only remnants of Monday night’s suffering. I say “miraculously,” though I’ll bet that I have last week’s flu shot to thank for my quick recovery. So today’s lesson: get your flu shot!

However, because of this cough, I am unable to add a voiceover today. I will try to remember to go back and add audio when I’m back to full health. Remind me if I forget.

In Sunday’s post, readers weighed in regarding Tolstoy’s lambasting of Shakespeare in his 1908 essay on the subject. (Click here for that post, and click here for the original post on Tolstoy’s distaste for Shakespeare.)

My own response to Tolstoy’s essay will echo some of the sentiments expressed by you readers, but I would like to conclude this little series by returning to where we began—to Dr. Johnson. In the first installment, we traced the growth of Shakespeare’s literary reputation through this essential critical voice. (Click here for the Johnson post.)

In his periodical essay on fiction in the fourth number of The Rambler (published in 1750), Johnson emphasizes the need for mimetic accuracy (what we would call “realism”), but he also insists that it is the artist’s responsibility to select “those parts of nature, which are most proper for imitation; greater care is required in representing life, which is so often discoloured by passion, or deformed by wickedness.”

Johnson seems to some extent to anticipate Tolstoy’s critical outlook here: realism is important, but writers also have a moral responsibility:

Many writers, for the sake of following nature, so mingle good and bad qualities in their principal personages, that they are both equally conspicuous; and as we accompany them through their adventures with delight, and are led by degrees to interest ourselves in their favour, we lose the abhorrence of their faults, because they do not hinder our pleasure, or, perhaps, regard them with some kindness for being united with so much merit.

Johnson seems to be thinking particularly of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones here, which had made a great splash the previous year. Fielding’s hero is an attractive, lovable, and kindhearted fellow, but he is also a bit of a slut: a slut with a heart of gold. But despite these promiscuous tendencies (or perhaps in part because of them), we still love him. And vice, for Johnson, when portrayed in fiction, “should always disgust.”

So when it comes to Shakespeare, Johnson praises but also equivocates. He seems to think that Shakespeare got it right most of the time but sometimes erred in his moral choices—for example, in the scene in which Hamlet decides not to kill the praying Claudius because he doesn’t want the usurper to go to heaven. This moment, for Johnson, crosses the line, as does the fate of Ophelia, which is brought about by Hamlet’s erratic behavior. (See Coleridge’s response to Johnson for an alternative view of the praying scene, discussed in this post.)

No doubt Tolstoy would agree with Johnson’s reading of this scene, but where the two writers differ is in their respective assessments of Shakespeare’s mimetic powers, and here they could not disagree more. As we have seen, Tolstoy thinks that Shakespeare’s characters are psychologically unrealistic, and that they mostly serve as mouthpieces for the author’s own ideas. Johnson, on the other hand, claims that mimesis is Shakespeare’s great power. In his Preface to his 1765 edition of Shakespeare’s plays, he writes:

His persons act and speak by the influence of those general passions and principles by which all minds are agitated, and the whole system of life is continued in motion. In writings of other poets a character is too often an individual; in those of Shakespeare it is commonly a species.

Shakespeare is, in short, “the poet of nature,” and “nothing can please many, and please long, but just representations of general nature.” This echoes Hamlet’s literary theory that he expresses to the visiting players before their performance: “For anything so o’erdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is to hold, as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature, to show virtue her feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of time his form and pressure.” And this, of course, goes back to Aristotle: the poet’s job is to represent nature.

So how do we account for such disparate assessments of Shakespeare’s representative powers? The answer is complex, but I think that it is explicable in three essential ways.

1. Pre-Romantic and Post-Romantic Ideas of Realism and Mimesis

In eighteenth century poetics (and Johnson is an essential example of this idea), human nature was considered something that we all share in common. Fielding, in his first chapter of Tom Jones, announces his subject to be “human nature,” which he holds is a universal theme. Alexander Pope, in his Essay on Criticism, writes that “True wit is Nature to advantage dressed, / What oft was thought but n’er so well expressed.” So, the poet’s mandate is to express what we all share in common in an interesting and novel way. Accurate representation will reflect this universality.

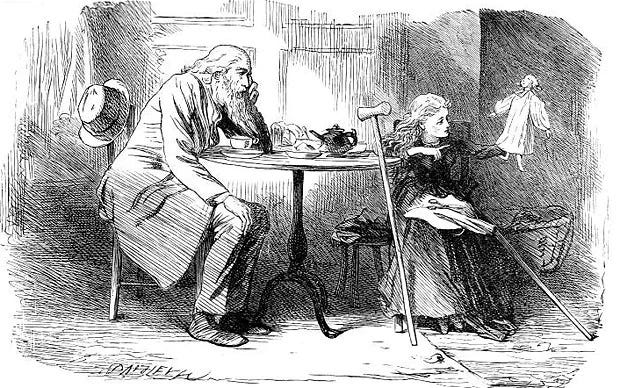

In the nineteenth century, on the other hand, under the parallel influences of Romanticism and the ascendency of the novel as a literary form, critical assessments of mimesis are all about the individual, the unique, eccentric aspects of each person that set them apart. Think of the bizarre, highly individualized habits and occupations of some of Dickens’s characters—Mr. Pocket in Great Expectations, for example, who keeps trying to pull himself up by his hair, or Jenny Wren or “Jenny Dolls” in Our Mutual Friend, who earns her living as a doll’s dressmaker as a response to the trauma caused by her father’s alcoholism and her own disabled body—another marker of her difference, or what we would call her “individuality.”

Tolstoy is clearly writing with this later sense of realism. He is, after all, a novelist, who creates sharply drawn, unforgettable characters, and the scope of the novel form allows him space to individualize his characters to such a level of detail that they seem to us like real people. Tolstoy does this as well as anyone ever has.

Shakespeare, on the other hand, though he predates Pope and Fielding, clearly has this more generalized idea of human nature in mind, just as Hamlet instructs the players to hold up the mirror to nature. He favors what some of my students call “relatability” over eccentricity in his construction of character. (I despise that word, by the way, but that is topic for another day. Don’t get me started. “Relatability”—ughh!)

Tolstoy’s criticism of Shakespeare is, then, anachronistic: he expects Shakespeare, who was writing the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, to conform to nineteenth-century critical ideas of character.

2. The Differences between the Drama and the Novel

Tolstoy’s assessment of Shakespeare also does not seem to account for the distinct forms of representation in the drama and the novel. The literary form of the novel, as we find it in Jane Austen and George Eliot and Tolstoy, is the form of interiority: we live inside our characters’ heads, largely through the techniques of free-indirect discourse and interior monologues, which allow the third-person narrator to move freely between omniscient and subjective perspectives. Or, alternatively, the novel allows for first-person narration, as in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, which is essentially voiced interiority.

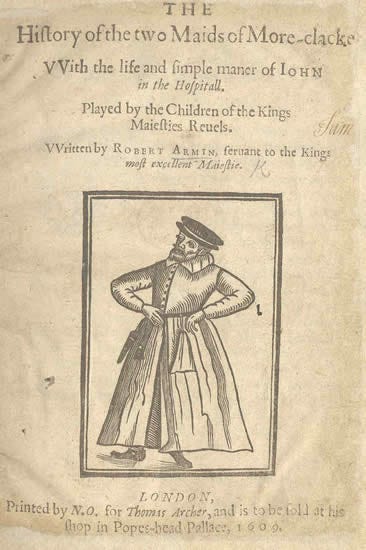

While we do get some interiority in Shakespeare, it works very differently because the literary form is different. On a textual level, we get it primarily through soliloquies. But—and this is where Tolstoy’s critical imagination fails him—on a dramatic level we also get it through the actor’s performance. Just as Duke Ellington wrote music for particular soloists in his band (like Johnny Hodges and Cootie Williams), Shakespeare wrote parts for particular actors in his company (like Richard Burbage and Robert Armin). He knew them intimately, and he knew what they could bring to the text. He trusted them to define character. The playwright must trust actors in a way that is not required of the novelist, who controls the entire mimetic space of the narrative.

We, as modern readers of Shakespeare, don’t just think of Hamlet as a character: we think specifically of Olivier’s Hamlet or Branagh’s Hamlet or Tennant’s Hamlet, and we think of how they each shape the role individually, even as they each stay true (or not?) to Shakespeare’s vision. Pierre Bezukhov, on the other hand, lives only in the pages of War and Peace and in our imaginations (film adaptations notwithstanding), which are shaped entirely by Tolstoy’s hand.

3. The Difficulty of Reading Language Historically

Finally, to speak plainly: Tolstoy is wrong. Shakespeare’s characters do not all speak the same way. Compare Falstaff’s language to Rosalind’s language to Lady Macbeth’s language. The differences are perhaps more difficult for twenty-first-century readers to discern, since we are unfamiliar with the nuances of Early Modern English, but they are there.

That said, it is true that some of the soliloquies may adopt a similar stately style, but the rhetorical space of the soliloquy is quite particular in Renaissance drama. As

wrote in response to the first Tolstoy post, “these speeches are also art in themselves (poems if you like). Although the context of the play and the character gives them more meaning, I don't think this unnatural quality takes away from the plays.” Another way to think of the speeches is that they are an example of that “universal” human nature that Johnson posits: a soliloquy in a dramatic context expresses what goes through our heads in moments like these, in a universal language, which we can all feel and understand. This is the representation of universality.And just as soliloquies have their own rhetorical spaces in the plays, so do the other uses of language. Shakespeare was working in an artistic form as well as a society in which people were expected to speak in specific ways in specific contexts: you would speak differently in church from how you would speak in court, or in the marketplace, or at home with your family. There were proper forms of speech, then as now. And since in the plays, we hear only the spoken dialogue in these ensemble scenes rather than the inner thoughts of our characters, it is, once again, up to the actors to show us character in spite of these rhetorical, contextual restrictions.

We still make rhetorical distinctions in how we speak in different contexts, but these distinctions are the products of our particular cultural moment, and future readers of twenty-first-century dramas may have trouble grasping these nuances. As

wrote in response to the first Tolstoy post, “four hundred years from now (I hope) when the American realist dramas of mid and late 20th century are read, will there seem a plain language common to all? I think maybe.”In order to understand historical forms of representation, we must read representation historically.

I see that once again, I have gone on longer than I expected. There is so much to say here, and I have only scratched the surface—so perhaps we will return to this “Why Shakespeare?” series at some point in the future. (I had, for example, planned a whole section of this post in which I would bring Coleridge back into the conversation. Another time!) But for now, it’s time to move on. Where to next? I’ll leave you in suspense. I’ll be back on Friday with the weekly roundup for paid subscribers and next week with something fresh for everyone.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Impressively comprehensive review of the reasons Tolstoy was wrong about Shakespeare, even while offering Tolstoy his enormous due. Great writers, as I think you remarked on earlier, can make eccentric critics, and Tolstoy, among his notable characteristics, was eccentric. All in all, these Shakespeare posts make an accessible and engaging brief review of two centuries (and more) of literary aesthetics. Well done!

Perhaps nothing showcases Tolstoy’s genius for interior representation and the limits of doing the same on the stage as when Tolstoy take us inside the mind of Levins dog Laska

What a great series of essays

Hope you continue to feel better!