Our books tend to outlive our bodies. Despite the countless texts lost to history, writing has proved a remarkable durable technology. Our oldest remaining texts date from around 3500 BCE, and if we consider the signifying possibilities of prehistoric cave paintings, we can set that date much earlier. Libraries are so full of the donated archives of the dead that many of them simply can’t accept any more.

But of course, one of the gifts of writing is that it allows the dead to speak to us. This is a kind of miracle. Every time a human stops breathing, we lose a bit of the human experience, but when we read old books, we are able to excavate some of it.

In the previous installment, we considered the story of Simonides and the invention of the art of memory. (If you haven’t read it, you can find it here.) The power of memory makes the self analogous to the text: both contain language and ideas that may be passed on to another.

One perhaps less obvious resonance of the Simonides story, however, is the simple idea that a text or a memory can record and thus keep “alive” objects or ideas or people that have apparently been destroyed or killed—or at least can provide a space for the living to contemplate the dead. It is, therefore, significant that the one detailed description in the novel of the burning of a heretic is related through Cromwell’s childhood memory of his witnessing of the burning of a Lollard woman (or a “Loller” as those in the crowd call her). The memory is several pages long and is striking in its vividness as it relates the sensual, embodied experience through sight, smell, sound, despite the lack of precision in terms of names and dates: “He cannot remember the year but he remembers the late April weather, fat raindrops dappling the pale new leaves.” The memory also makes clear the morbid juxtaposition between the physical remains of the victim of burning, as her friends arrive afterwards to collect them as well as they can, and the clear memory of her among those friends; one of these survivors “placed on the back of his hand a smear of mud and grit, fat and ash. ‘Joan Boughton,’ she said,” who, it turns out, was a real person and not Mantel’s invention—which may partly be the point. The “essence” of Joan Boughton’s selfhood is not to be found in the physical remains, which are indistinguishable from any other, but in the memory, or the text.

That indistinguishability makes possible the fraudulent relics of supposed saints’ remains, but those who execute heretics perhaps make the mistake of believing that annihilating the body will also destroy the text that is the self. That text may still proliferate in various forms: through writing, through notoriety, or through a boy’s memory, where it may lay dormant for half a lifetime and then emerge to challenge the burnings of others.

Cromwell is often unsuccessful in such challenges, as in the case of John Frith, “a gentle, slender young boy, a scholar in Greek,” whom he tries and fails to protect from the anti-heretical zeal of Thomas More. Cromwell attempts to convince More that Frith should be saved in terms similar to Bilney’s notion that he could persuade the pope to choose the path of reform:

I’m not asking you to agree with John—you think he’s a heretic, perhaps he is a heretic—I’m asking you to concede just this, and tell it to the king, that Frith is a pure soul, he is a fine scholar, so let him live. If his doctrine is false and yours is true you can talk him back to you, you are an eloquent man, you are the great persuader of our age, not me—talk him back to Rome, if you can. But if he dies you will never know, will you, if you could have won his soul?

Though perhaps this is not as desperately delusional as Bilney believing that he can convince the pope through logical persuasion, the fact that More does not even respond to Cromwell’s plea is particularly telling. What matters to More in this case is less about the individual soul and more about what he sees as the problem of the proliferating text.

For More, translating the Bible into English is heretical for precisely this reason: access to the Bible for the uninitiated, for those without specialized scholarly knowledge and dedication to established doctrine, would allow for skepticism, for nonconformity. And translation, for More, is a perilous occupation, since every ambiguous word of scripture (whether in Latin, Greek, or Hebrew) might lead the translator into heretical error. Tyndale, the fugitive translator of the Bible into English, is More’s great enemy. Much of Tyndale’s language eventually made its way into the King James Bible, whose prose, for many English speakers, is etched into our minds. Mantel takes advantage of this familiarity, as she invites her readers to imagine a time when such language was a new, exciting world of possibilities. But by invoking this language, she also makes clear the dangers it originally carried with it:

Tyndale says, now abideth faith, hope and love, even these three; but the greatest of these is love.

Thomas More thinks it is a wicked mistranslation. He insists on “charity.” He would chain you up, for a mistranslation. He would, for a difference in your Greek, kill you.

Cromwell, by focusing on this scriptural passage, looks forward to what would become a central tenet of modern Protestant Christianity, while More’s rejection of the translation insists upon the transactional power of the sacraments and the central role of the church. But more to the point is the assertion of the connection between textual error and bodily punishment—though Cromwell actually understates the case: punishment derives not just from mistranslation, but from the mere act of translation into the vernacular. Vernacular texts may be internalized, assimilated into the self. No priestly intermediary required.

Earlier in the novel, so-called heretics like Bilney and Bainham have recanted to save themselves from the fire, only to “relapse” and return to their testimonies, sometimes literally distributing and proliferating the illicit texts in the process. Furthermore, the authorities have failed to capture and interrogate Tyndale during his time in England, and thus they have failed to prevent the most significant source of proliferation of all. The interrogation of heretics has, therefore, become more uncompromising, because that essence of self, that textual assimilation, must be revealed at all costs in order to curtail further proliferation:

More says it does not matter if you lie to heretics, or trick them into a confession. They have no right to silence, even if they know speech will incriminate them; if they will not speak, then break their fingers, burn them with irons, hang them up by their wrists. It is legitimate, and indeed More goes further; it is blessed.

Bodies, like books, must be examined for heretical content without regard for the physical object itself, and once the heretical text has been revealed in either case, its container must be annihilated. But the text lives on, which is why More’s mission to root out what he calls heresy is doomed.

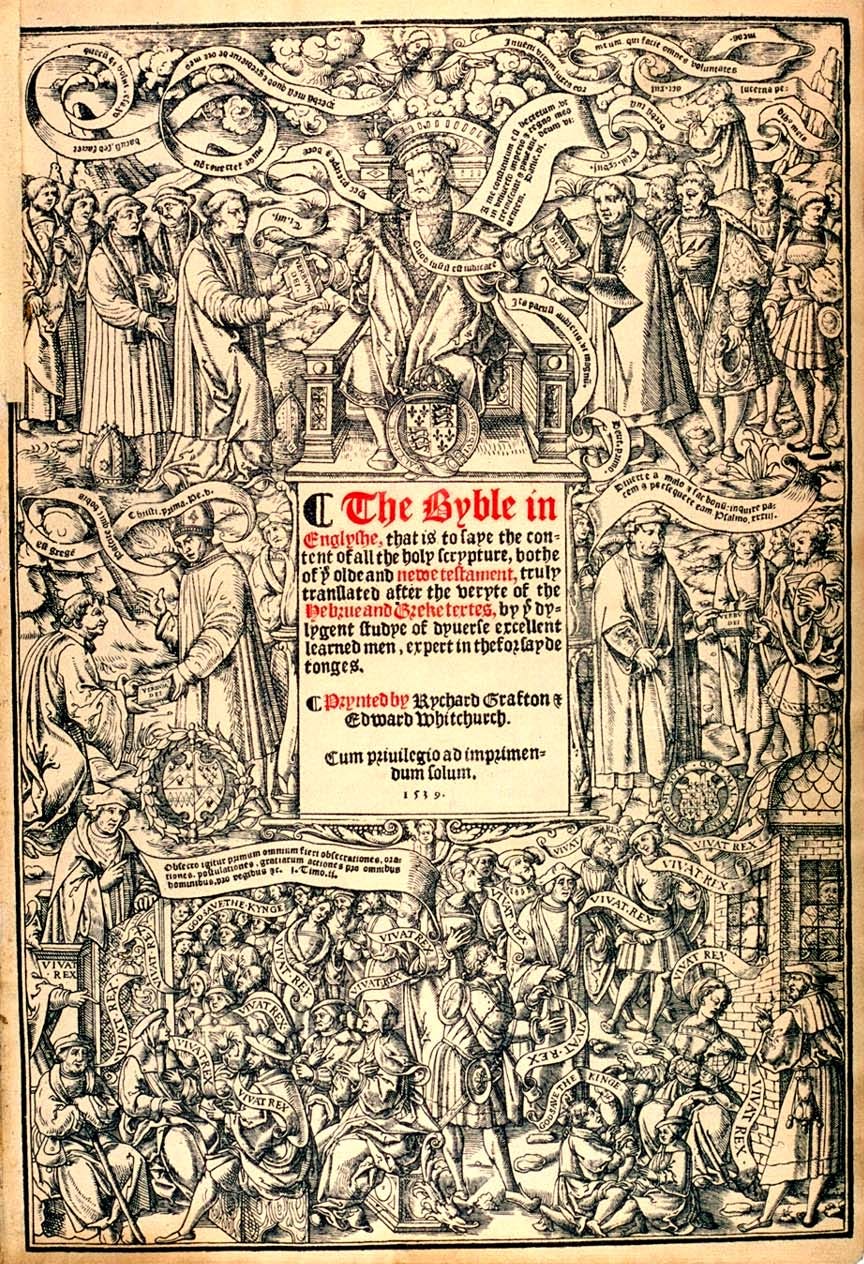

One source of interest in the context of a work of historical fiction like Wolf Hall is to imagine what it would have been like not to know what would come next—not to know whether or not an English Bible would ever be widely available. When the historical John Frith was executed in 1533, no one knew that it would become a mandate that every parish church in England must possess an English Bible by 1538, or that the “Great Bible,” endorsed by the king, would be printed and distributed throughout the country by 1539, even though more than half of the first printing in Paris would be seized and burned by French authorities. By 1535, of course, Thomas More himself would be dead, executed for treason, and by 1540, the same would be true of Cromwell. The bodies continue to pile up, and books continue to burn.

The texts remain. The dead speak to us.