What Can Prince Teach Us about the Icelandic Sagas?

Part one: “When Doves Cry,” the song that followed me around Europe

Death, close sister

of Odin’s enemy,

stands on the ness:

with resolution

and without remorse

I will gladly await my own.

—Sonnatorek, attributed to Egil Skallagrimson, trans. Bernard Scudder

That flaming opening guitar lick; it shakes you.

That oh-so-delicate keyboard riff, tiptoeing down the stairs. Those propulsive drums, compressed and syncopated.

“Animals strike curious poses.”

Despite his diminutive stature, Prince was a towering figure throughout my teenage years. His music exuded a sexual energy that hinted at a mysterious, sensual world beyond my young imaginings. The first of his songs that I heard, “Little Red Corvette,” was irresistibly dark and moody but also infectious—an illicit ear-worm in a more innocent era. The first time I saw him on TV was on the video for “1999,” and he was like nothing I had ever seen—my generation’s Ziggy Stardust, visiting us from his purple planet, carrying his message of apocalyptic hedonism: “When I woke up this morning, could have sworn it was judgment day.”

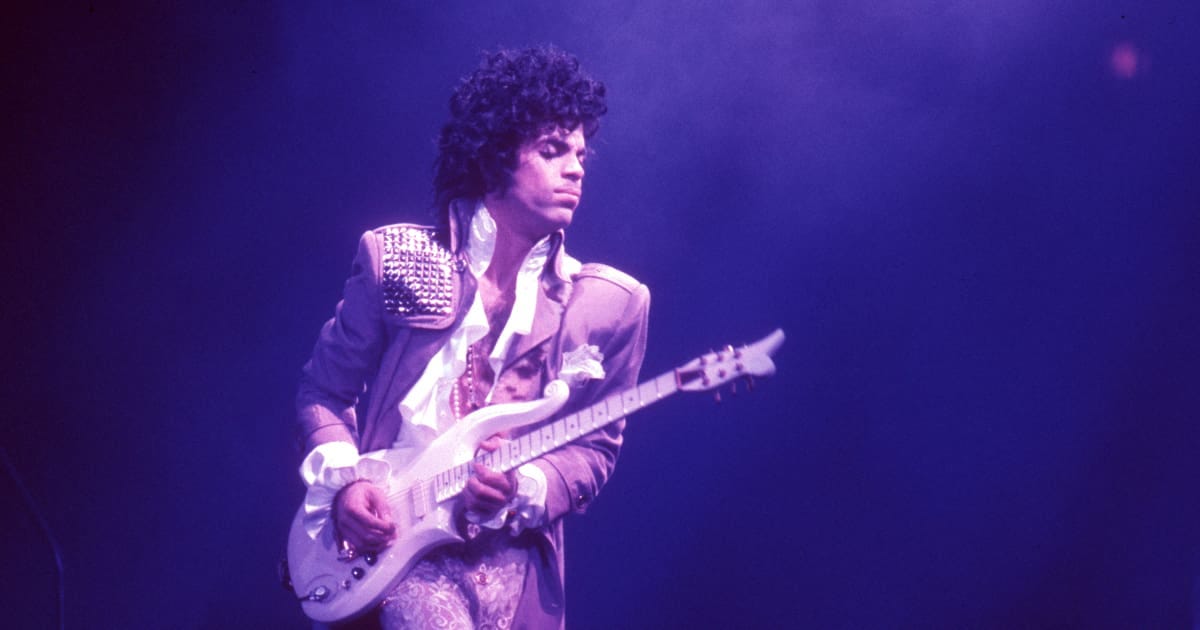

Before the release of Purple Rain, the album that elevated him to musical (as well as eponymous) royalty, I began to notice that the “album-oriented rock” station that dominated my listening in those years did not play his music, even though he was a smoking hot rock guitarist to rival Hendrix or Clapton. Prince was beginning to teach me of the unspoken racism of the music world: for what could exclude him but his skin color? Hendrix, in regular rotation on classic-rock radio, was the exception that proved the rule, the one black artist who was allowed to enter rock Valhalla. (My usual station didn’t even play Sly Stone or Stevie Wonder or Tina Turner.) I had to seek out Prince on pop radio, which was a bit more inclusive (in some ways) and by buying his records.

In May of 1984, my family was about to embark on a year-long adventure abroad: my father was going to Oxford for his sabbatical, and so I was going to attend an English school. Before the beginning of the academic year, my family would spend the summer traveling around western Europe on a shoestring budget (which was still possible at that time; the current edition of Frommer’s was Europe on $35 a day, a shocking price hike from the previous edition’s $25). One day, shortly before leaving home, I heard that thrilling opening to “When Doves Cry” for the first time on the radio. It shook me: it was an order of magnitude greater than anything on 1999, as brilliant as that record had been. The Purple Rain album was not yet out, but that song, its first single, followed me from North Carolina to the UK and all around Europe that summer. I would hear snatches in cafes, in cabs, in hotel lobbies. The sound of that keyboard riff emanated from passing cars and out of boomboxes carried on young shoulders in cities from Bruges to Rome.

In Venice, I was waiting for my parents in the Piazza San Marco, amidst a thousand pigeons (which are, of course, dove-like) when a beautiful, raven-haired girl, maybe a year or two older than me, carrying a Sony Walkman and wearing headphones, boots, and a mini-skirt, strolled past, singing along with Prince in a musical Venetian accent: “Animals strike curious poses, / they feel the heat, the heat between me and you.” She saw me smile and said: “Is a good song, yes?”

I didn’t understand how she knew that I was an English speaker, but it was probably written all over me.

I didn’t get to hear the album when it dropped in late June, and I had still only heard the first single after I settled into my school in Oxford in September. I had to save my pence (and my pounds—newly available in coin form in 1984) to buy the cassette, since I had no record player in the UK, and CDs were not yet a thing.

I was not prepared for the volcanic eruption that would occur when I popped the tape into my cheap boombox. Has there ever been a more powerful opening track to an album than “Let’s Go Crazy”? It was a great concert opener too. If you are too young (or too old) to have experienced the whole Purple Rain phenomenon in real time, then take a look at this performance of “Let’s Go Crazy” from 1985. It’s mind-blowingly good:

How could he play the guitar while dancing like that? The band was so tight, and they looked incredible. He could do anything.

But it’s not just the musical energy in the recording: it’s the energy in combination with the song’s essential strangeness, and a return to the apocalyptic sensibility of the title track to 1999, but this time in a more ambiguous mode.

It begins with Prince channeling the tones of an evangelical preacher, and despite his well-known religiosity, it sounds heavily ironic in this context, especially as it turns from the “never-ending happiness” of “the afterworld” to “this life”:

Because in this life,

things are much harder than in the afterworld;

in this life,

you’re on your own.

And if the elevator tries to bring you down,

go crazy, punch a higher floor.

At which point, the simple, infectious power-chord riff takes over and carries us through the song in a state of ecstatic delirium—in anticipation of the end that is inevitably coming:

We're all excited,

but we don't know why,

maybe it's 'cause,

we're all gonna die,

and when we do,

what's it all for?

You better live now,

before the grim reaper come knocking on your door

The song culminates in a Princely avalanche of an unaccompanied guitar solo, before the band comes back in to create a tutti crescendo, concluding with the chorus shouting, “take it away!”

It is, however, just the beginning of the journey—and it is a journey in two parts, through an erotic nightmare of unquenchable desire on side one of the album, to . . . “something else” on side two, but it’s not “the afterworld”; it’s “Purple Rain,” whatever that is.

This is not to suggest that the album is a coherent, consistent narrative, but rather that it takes the listener on a kind of psychological and musical ride, which lends itself to experience rather than to analysis—which is why you should stop reading this right now and go and listen to the album, and then come back and finish reading afterwards.

It’s fine. I’ll wait.

“Hold on,” the reader protests. “I came here to read about the Icelandic sagas, but so far you’ve given us half a personal essay about Prince and your teenage years. And I know that you don’t feel confident writing personal essays, because I read your piece about it last October. What’s going on here, Halbrooks? What are you trying to pull?”

OK, fair enough. I should explain, or at least begin to explain. I hadn’t listened to Purple Rain straight through in years until a few days ago. I really haven’t needed to listen to it, since I internalized the whole thing through countless listens decades ago. I know every lyric, every guitar note, every downbeat. But a couple of weeks ago, I kept hearing inexplicable mental echoes of Prince as I taught Egil’s Saga, a thirteenth-century Icelandic narrative about a viking poet, which is set in the tenth century. The saga is written in prose, but it includes poems that were supposedly composed by the historical Egil, though there is no scholarly consensus about these attributions.

One of these poems is the famous Sonnatorek, or “On the Death of Sons.” It’s a haunting and haunted poem, which resonates with my discussion of Hrethel’s sorrow in Beowulf from a couple of weeks ago. (Actually, I cited Egil in that piece, which is linked here.) I have read and taught this saga and this poem many times, but for some reason, this time a succession of songs from Purple Rain kept going through my head. It was almost like a play/pause button: when I would start reading, Prince would begin playing in my mind; when I would stop reading, the music would stop.

My brain was clearly putting these two works of art together, but I couldn’t figure out why. Since my best ideas often come from these accidental juxtapositions, from these odd bits of synchronicity, I set out to write this essay in search of an answer.

And I think that I have found one, though it is not simple, nor is it definitive. To understand what Prince can teach us about the Icelandic sagas, we will have to follow the wild ride through both sides of Purple Rain—from the erotic, apocalyptic abyss of side one to the self-sacrificing enlightenment of side two—and the equally wide ride through Egil’s extraordinarily violent poetic career, from his devastatingly ironic praise poem for King Eric Bloodaxe, to his love-poems to Asgerd, to his mourning the deaths of his sons.

And we will have to ask the question: what is “Purple Rain”?

We’ll pick it up here next week. Don’t forget to listen to Prince in the meantime. I’ve linked to this sublime, sixteen-minute performance of “Purple Rain” from 1985. It’s worth watching to the end.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet guitar to yours.

Looking forward to seeing where you go with this! And to finding out what the heck Purple Rain is. On a personal note, England was also where I had a big Prince experience: seeing the Purple Rain movie in London. So I always associate Prince with that city somehow.

I’m glad to see this kind of intersection of pop and academia, which I guess is pretty normal now. Way back when I was a freshman in one of those Great Books courses, the topic of discussion was the Apollonian vs the Dionysian mode, and how the two could be blended. I popped off with “You know who does a great job with that? The Who!” The discussion leader, an art professor with a specialty in Modernist art and architecture, gave me a patronizing look and said, “Oh, The Who. Aren’t they wonderful.” Afterwards, my classmates ribbed me about what a sick burn that was.

Ahhhh to go back in time and see Prince live. That’s a dream. I enjoy the way you talk about the way he creates such ethereal music. First, by being exceptional at playing the guitar. Second, at creating a full piece of art, where the composition’s beginning is almost a separate experience itself. And third, through the visual experience (also of the body). And I guess even when we just listen to Prince, we conjure these performances. Somehow you manage to explain the unexplainable.

Can’t wait to see here this goes next...