This is the weekly roundup of reviews and recommendations for paid subscribers. To access the entire archive of “Bird-Bolts,” and to receive the new edition each week, please consider supporting my work by upgrading your subscription for the price of one fancy coffee a month. Paid subscribers also get access to my “Rotation” playlist and can participate in Canonical Matchmaking. (No, it’s not a dating service.)

Reading

I’m closing out the final three Wednesdays of the year with essays on Hilary Mantel’s novel Wolf Hall, and so in these Friday installments I’ll include a bit of followup—some ideas that I didn’t have room for in the main essays. Today, I would like briefly to consider Mantel’s narrative voice and what makes it unique. A number of critics have noted how she moves through first and third person, and even sometimes second person, and how she makes arresting use of the present tense and jumps back and forth through time.

While her technical mastery is well established, I think that she achieves her effects in ways that are more difficult to define. As an example, let’s take a moment from early in Wolf Hall, the beginning of the chapter “An Occult History of Britain”:

Once, in the days of time immemorial, there was a king of Greece who had thirty-three daughters. Each of these daughters rose up in revolt and murdered her husband. Perplexed as to how he had bred such rebels, but not wanting to kill his own flesh and blood, their princely father exiled them and set them adrift in a rudderless ship.

The ship was provisioned for six months. By the end of this period, the winds and tides had carried them to the edge of the known earth. They landed on an island shrouded in mist. As it had no name, the eldest of the killers gave it hers: Albina.

When they hit shore, they were hungry and avid for male flesh. But there were no men to be found. The island was home only to demons.

The thirty-three princesses mated with the demons and gave birth to a race of giants, who in turn mated with their mothers and produced more of their kind. These giants spread over the whole landmass of Britain. There were no priests, no churches and no laws. There was also no way of telling time.

After eight centuries of rule, they were overthrown by Trojan Brutus.

Mantel drops this in the middle of her narrative, most of which has been in present tense, as Cromwell and company are dealing with the logistical problems of accommodating the needs of Cardinal Wolsey, who has just fallen from the king’s favor. What is this absurd history doing here? What does it have to do with anything?

More to the point: who is this narrator? Is this a modern voice filtering an ancient source? Or is it meant to be a sixteenth-century voice? Is the voice ironic? The understated use of “perplexed” in the third sentence certainly suggests irony—but irony to what end? Certainly, it is a misogynistic voice, but the misogyny seems ironic as well, since the story is so over the top that it is clearly not meant to be believed, even by the most gullible readers or listeners.

After this passage, the narrator continues with this lightening-speed pseudo-history, which at some point blends with history and introduces the Tudors. Actually, it’s at a particular point: Trojan Brutus leads us eventually to his legendary descendent King Arthur, who leads us to Prince Arthur, son of Henry Tudor and dead brother of the current king.

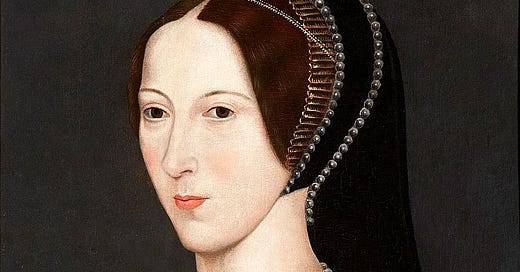

Then, suddenly, it is 1521 (still several years before the cardinal’s fall), and a new young lady appears at court: Anne Boleyn.

What is going on here? Where have we gone, and why have we gone there?

Here is my reading: we must, somehow, explain how Cardinal Wolsey, the most formidable man in England after the king, has fallen so far from the height of his power. To do this we must go back in time, but how far back? To Anne Boleyn’s arrival at court? No, further. To the death of Prince Arthur? No, further. To the rise of the Tudors? No, further.

We must go all the way back—to the beginning of this place, this England. But, of course, we cannot do that, because beyond a certain point, time dissolves into unknowing—which means that our explanation dissolves into unknowing. Our voice takes on the quality of a dark fairy tale—one with feminine monsters and masculine heroes—the kind that mischievous parents might tell their wicked children to scare them, except they are winking the whole time, because we know that it’s a story they’ve made up in order to make a point rather than to uncover history. What kind of world made Anne Boleyn? What sort of explanation might we find for her? The fact that it is a misogynistic voice folds into the staining of Anne’s reputation by her critics, but the irony in its tone disarms the misogyny.

So the voice is not a person whom we can put a name to, nor can we locate it specifically in time or space. It is a living voice that circulates through the minds of our characters—of Cromwell, of Wolsey, of George Cavendish—through the mind of our author, and into the minds of readers. It is a consciousness that we feel we share in this triangular relationship, the living and the dead.

And this is why it is a supreme narrative voice for historical fiction. Mantel is not showing off her research or using stiff, artificial Tudor dialect to create historical effects. Instead, she is creating a voice that seems to unite our consciousness with these reanimated versions of these real people, long since buried. That’s a kind of miracle.

The Rotation

I warned you last week that I would add some Christmas music (in addition to Handel’s Messiah), and I have done so. But I promise that it is worth listening to, and if you still don’t believe me, it is easy to avoid it because I’ve packed it all at the end of the playlist.

First up is Wynton Marsalis’s classic Crescent City Christmas Card, followed by Norah Jones’s Christmas album, which came out last year. Finally, there is the Boston Camerata’s Medieval Christmas, which has very few familiar tunes on it, so you could probably listen to the whole thing and not even realize that it is a Christmas album.

At the top of the Rotation this week, and for the rest of the year, is Debbie Weisman’s Wolf Hall soundtrack, which I will have more to say about in next week’s edition.

Here is the link:

The Rotation from Personal Canon Formation

Please look for my guest essay today on negative capability for the collaborative newsletter The Inner Life:

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

John,

I think one effect of that passage is to make the current characters more "real" in comparison to the myth, moving from epic primordial time back to the "present," even if the present is 500 years ago.

Great close read! And a technique to keep in mind.

Best,

David

Is she hinting that much mythology is based around women’s role in man’s downfall (Eve, Pandora, […], Anne Boleyn etc.)