A City for Women: Christine de Pizan Claps Back

Clapping Back to Misogyny from 1402 to 1949, part two

In last week’s post, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath invoked the “shadow canon,” a lost line of unrealized works by ingenious women who never had an opportunity to write them. The Wife is responding to a long tradition of misogynistic writing going back to St. Jerome and continuing through Jean de Meun, one of the authors of the popular French allegory The Romance of the Rose, and Matheolus, a late thirteenth-century cleric who wrote at length about the miseries of marriage for men and their suffering at the hands of women. The opening lines of The Wife of Bath’s Prologue are actually drawn from Jerome’s antifeminist tract Against Jovinian, a diatribe against women and marriage, though the Wife recasts them to argue essentially the opposite point: God bade us to multiply (“that is a doctrine I can well understand!”); God made our genitals; sex is a great blessing; and women should be in charge.

The Wife is such a powerful figure that it is sometimes easy to forget that she is the creation of a man, and Chaucer presents her through such complex layers of irony that she belies attempts to make definitive claims about her. Is she a powerful response to misogyny, or is she an ironic continuation of the antifeminist tradition? Or is she, somehow, both at once?

These are fair questions, because at times she seems to reflect the complaints about women made by Matheolus in his Lamentations (late thirteenth century), and at other times, she seems to anticipate the later arguments of Chaucer’s younger contemporary, Christine de Pizan, who responds to Matheolus in her Book of the City of Ladies.

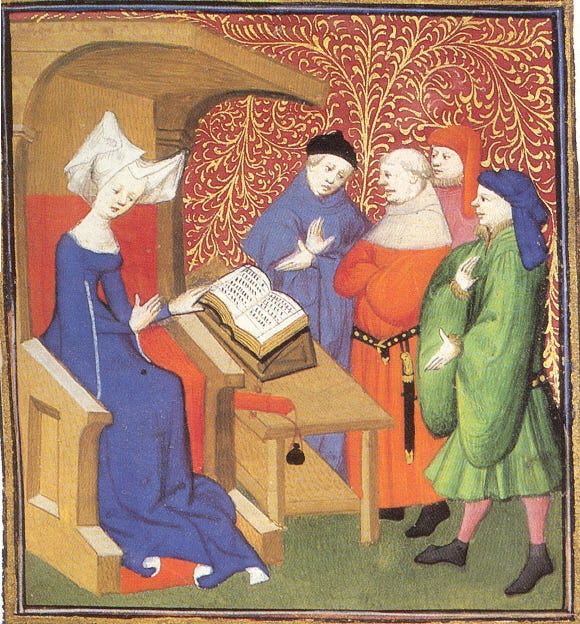

Christine, by any measure, is an extraordinary figure. Though she was born in Italy, she moved to France with her family as an infant and grew up in court circles. Apparently, her father encouraged her reading and literary education, which was unusual at the time (to say the least). She married in her teens, and (also unusual at the time) she and her husband were actually in love. (She would later write about the “sweetness” of her marriage.) Unfortunately, both her father and her husband died within a couple of years of each other, leaving Christine with no fortune or income and with three children.

Most women at the time responded to widowhood like the Wife of Bath does, by remarrying—four times in the Wife’s case. Others took refuge in holy orders and retired to convents. Christine, however, took the singular step, as she describes it, of “becoming a man” and earning her own income through her writing.

It is difficult to express how unusual this was. It was more than unusual. It was unique. Women were not writers, or at least they were not openly so. (There were exceptions, of course, like Marie de France, but they were few and far between.) What’s more: she pulled it off with dazzling success. She wrote prolifically for the next three decades: lyric poems, ballads, treatises, allegories, dream visions, and even a sort of historical commentary in her final work, The Tale of Joan of Arc.

Christine was well aware of her singularity, but she was also certain that there was a shadow canon, a long history of silenced women. As Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski has pointed out, she echoes the Wife of Bath on this topic in her Cupid’s Letter of 1399:

But if women had written the books, I know for sure that things would be different; for they know well that they have been falsely blamed. Things are not divided up evenly, for the strongest ones take the biggest part, and the one who cuts up things takes the best part for himself.1

Christine is responding here to a history of finger pointing that goes back to Adam and Eve in the Garden. Who gave you the fruit? It was that woman! She is to blame. Or as Chaucer’s rooster Chaunticleer exclaims (and mistranslates) in The Nun’s Priest’s Tale: “Mulier est hominus confusio” (“woman is the cause of man’s ruin”).2 While Christine takes up this topic throughout her writing, she does so most methodically in two works: The Debate on the Romance of the Rose (1402) and The Book of the City of Ladies (circa 1405).

The first of these is a response to Jean de Meun’s continuation of a popular French allegory that tells the story of a lover’s attempt to attain a rose (i.e. sex) and his encounters with all sorts of allegorical figures along the way. Christine is reacting against the obscenity of the poem, but also against misogynistic speeches by figures like “Jealous Husband.” She begins her response with what rhetorical treatises call “the humility topos,” which is an expression of the writer’s inadequacy. This is a common medieval device. We see this in the General Prologue to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, for example, when the narrator apologizes to the reader and tells us that his “wit is short.”

When gendered female, however, the humility topos reads differently, much in the way the Rodgers and Hart standard “My Funny Valentine” has a markedly different effect depending on the gender of the singer. When a woman sings it to a man, it’s kind of sweet:

My funny valentine, sweet comic valentine,

You make me smile with my heart,

Your looks are laughable, unphotographable,

But you’re my favorite work of art.

Is your figure less than Greek?

Is your mouth a little weak?

When you open it to speak,

Are you smart?

When a man sings it to a woman, however, it becomes much darker, because of gender norms that put greater emphasis on a woman’s appearance and because society tells us that it is more acceptable (or even charming) for a man to be funny looking and bumbling than for a woman to be so. The regendering of the song exposes social inequities. In the case of the humility topos, the effect is inverted. When Chaucer tells us that he isn’t smart, we know that he is being affably ironic. When Christine does this, on the other hand, this is not so clear, because she is echoing the very misogynistic tradition to which she is responding:

I, Christine de Pizan, an ignorant woman of inadequate opinion—for this your wisdom may well hold the insignificance of my arguments in disdain—beg you to take into consideration my female weakness.3

Students often respond negatively to this passage: why is she ashamed of her womanhood? However, Christine is actually cleverly inverting misogyny here, as she goes on to demonstrate her rhetorical mastery in her deconstruction of the claims of Jean de Meun’s poem with regard to women. If women are so powerless and stupid, Christine asks, then how are they able to wreak all of this supposed havoc? How are they able so effectively to deceive and control their husbands, as the misogynists claim? How is it that men have all of the power but cannot control the women whom they pronounce to be ignorant and weak?

Christine employs an even more powerful variation of this rhetorical move in The Book of the City of Ladies. Here Christine begins with an anecdote in which she takes down a book from the shelf for a bit of light reading. Once again, this is a convention in late medieval literature. In both of Chaucer’s poems Book of the Duchess and The House of Fame, for example, the narrator takes up a book and falls asleep while reading in order to have the main narrative begin in a dream, which responds in some way to the book that he was reading.

In Christine’s version of this pattern, the book she takes up is Matheolus’s Lamentations, which is an extended complaint about women and how they destroy their husbands. After reading this, along with other misogynistic writing, she falls into despair:

I came to the conclusion that God had surely created a vile thing when He created woman. Indeed, I was astounded that such a fine craftsman could have wished to make such an appalling object which, as these writers would have it, is like a vessel in which all the sin and evil of the world has been collected and preserved. This thought inspired such a great sense of disgust and sadness in me that I began to despise myself and the whole of my sex as an aberration in nature.4

She goes on to wish that God had not made her live “in a female body.” However, in the midst of her despair, three women appear to her with the auspicious names of Reason, Rectitude, and Justice. They explain to her that all of this writing is slanderous, that men have abused their power, and that that these antifeminist claims need to be corrected.

Why, Christine asks, do men tell such lies about women? Reason answers that some do this to cover their own sins, some because of a “bodily impediment” (!), and some because they simply love to slander others. Furthermore, “there are also some who do so because they like to flaunt their erudition: they have come across these views in books and so like to quote the authors whom they have read.”

This last reason is particularly resonant, not only because it emphasizes the embedded misogyny of the received canon, but also because it implicitly questions an epistemology that privileges male written authority over female lived experience. The Wife of Bath famously claims that experience is enough for her to speak about marriage, that she doesn’t need “auctoritee” or written authorities.

Rectitude goes on to argue for the education of women, against those who would like to keep them in ignorance, so that women may respond to such slander with rhetorical and literary tools. To do so, they must build a “city of ladies” in which women may be educated and may support each other without the interference of the haters. After all, Reason says, “if it were the custom to send little girls to school and have them study the sciences, as one does in the case of boys, they would learn just as perfectly and would understand the subtleties of the arts and sciences as boys do.”

And so we introduce a theme that will appear again and again throughout this series in the coming weeks, in the writings of de Staël, Wollstonecraft, Woolf, and others: the subjugation of women begins with inequities in education. Men’s complaints about the supposed ignorance of women beg the question: if they are so ignorant, then why not provide them with an education? The answer is obvious, though not often stated explicitly: to do so would be to undermine the gendered power structures that maintain women in subservient positions.

Christine does not follow the argument to this point of questioning the patriarchy, but this would have been impossible in her historical moment, and it would have given force to the arguments of the misogynists that women want control over men (as the Wife of Bath does). However, the fact remains that Christine serves as a living example of her own claims: if given the chance, women will emerge from the shadow canon, achieve autonomy, and clap back to millennia of misogyny.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

The translation from the French here is by Blumenfeld-Kosinski.

Chaunticleer tells Pertolote, his beloved hen, that the Latin means “Womman is mannes joye and al his blis.” He is one smooth-talking rooster.

The translation from the French here is by Christine McWebb.

The translation from the French here is by Rosalind Brown-Grant.

Many echoes of this fine essay in Benjamin Franklin's "The Speech of Polly Baker." Franklin isn't widely remembered as a satirist now, but he adopts Polly's voice in that sketch and skewers the judges who are about to fine her for an unplanned pregnancy. Maybe you're not in a position to say, but I think Substack represents a larger pendulum swing in publishing. Certainly women exert much more influence on the book marketplace now as a majority of book buyers (wouldn't be shocked if they are also a majority of paying subscribers on the platform).

The new Judy Chicago museum exhibit is also inspired by the book: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/judy-chicago-new-museum-survey-art-historical-women-2298176/amp-page