Listening to Black Women & Radical Joy through the 2023 Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival

Clapping Back to Misogyny, part three

Dear Reader,

Today I am delighted to feature my first guest writer, my brilliant colleague and dear friend Dr. Laura Vrana. Laura is a specialist in African American poetry and has published extensively on the subject. In addition to numerous articles and book chapters, she has co-edited The Collected Poems of Lorenzo Thomas, published in 2019 by Wesleyan University Press, and she has a forthcoming book with Ohio State University Press entitled Writing Transgressions: Prestige, Publishing, & Black Women’s Poetic Performance. Today she is reflecting on her experience at the 2023 Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival, a commemoration of the original festival, which was held in 1973. I am honored that Laura is sharing this here, and I am sure that you will enjoy it and will want to seek out the wonderful work that she cites.

Yours,

John

In recent years, it has become something of a societal cliché among well-meaning (white) progressives to intone with an admixture of gravitas and sardonic humor the message: “Listen to Black women.” This phrase initially gained limited cultural purchase in the aftermath of the 2016 election, as a kind of implicit rebuke to the fact (indisputable but somehow a horrifying surprise to many) that a statistical majority of white women had voted for a staggeringly misogynistic bigot. It then started to become an ominous, constant refrain—appearing ubiquitously on protest signs, t-shirts, and social media—amid the rise of white supremacist terror during that presidency and throughout and after the nail-biting election three years ago that yielded the elevation of Biden and the first African American female vice-president, due primarily to Black women’s organizing.

This phrase calls upon the rest of American society to take seriously the warnings (however seemingly dire) tendered by this group that has been historically marginalized at every turn and therefore proves especially attuned to how hollow many promises of change turn out to be, a useful bellwether. (Anna Julia Cooper arguably first embodied this line of Black feminist thinking in her 1892 claim that: “Only the BLACK WOMAN can say when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood…then and there whole Negro race enters with me.” Since then, this idea has blossomed into the broader message that Black women are the canary in the coalmine, the demographic group whose well-being or lack thereof ought to be the barometer by which we measure progress.) The necessary counterpoint is harder to reduce to a pithy aphorism: that Black women cannot, must not, be expected to swoop in and save us from dire political and electoral outcomes, that the rest of us remaining complacent and offloading the burden of organizing and advocating for meaningful change is not tenable.

In my corner of the world with my limited skillset, I try to listen to Black women and encourage others to do so through the teaching of African American literature and especially poetry, which allows students to discover how evergreen their ideas prove. I have been thinking more and more lately about this inter-generational, trans-temporal, time-traveling quality of Black women’s poetic production. As part of this, just last week, I had the life-giving opportunity to inhabit for four days an alternative reality in which hundreds of people gathered to do nothing but listen lovingly, attentively to Black women, in a space that felt suspended outside the normal constraints of time and academia: the 2023 Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival1 at HBCU Jackson State University in Jackson, Mississippi.

The original Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival, of which this event was a 50th-anniversary commemoration, unfolded in Jackson from November 4-7, 1973, organized by poet-professor Margaret Walker.2 The list of attendees is mind-blowing to anyone familiar with 20th-century African American literary and cultural history; featured speaker-performers included the creative-intellectuals Alice Walker, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, June Jordan, Lucille Clifton, Audre Lorde, Carolyn Rodgers, Mari Evans, Naomi Madgett, and Sarah Fabio. Amid the Black Arts Movement, in an era sans social media and in which traveling into the deep South proved rife with hazards for people of color, these women came together in honor of the 200th anniversary of Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. (This was just before the Combahee River Collective began gathering and four years before the famed statement that group issued that encapsulated many now-foundational Black feminist ideals.) The readings, performances, and scholarly talks that resulted have become the stuff of lore, and the 1973 festival serves as a touchstone in the trajectory of Black (women’s) writing and feminist thought.

As such, this 2023 re-gathering was for all attendees (scholars, writers, arts administrators and organizers, and even elementary and secondary school teachers and students from the local community) a kind of time-traveling device, linking the lodestar moments of 1773, 1973, and our present in a continuum to enjoin all present to validate, celebrate, and listen to Black women’s creative and intellectual productions, past and present. Even as—perhaps because—the 2023 sociopolitical backdrop does not necessarily feel that tonally different from or significantly better than the urgency of the 1973 landscape, the predominant theme that unified every event (from scholarly presentations to poetry readings to public talks with Alice Walker, Imani Perry, Angie Thomas, Nic Stone, and Nikole Hannah-Jones) was one of invoking radical joy. This was no conventional academic conference, although every moment exuded thoughtfulness, rigorous care, and tender knowledge about the riches of African American women’s literary legacies. But the event proved that treating this body of work with seriousness and grappling with the accompanying cultural histories it invokes need not disbar (indeed, ought to especially invite) a posture of celebration, finding joy, and dwelling in the radically transformative potential of happiness as a force that can be weaponized as a mode of survival when operating within problematic, hegemonic institutions—societal and/or academic.

As perhaps the best encapsulation of this spirit, in her public conversation with Dr. Ebony Lumumba, renowned author Alice Walker repeatedly referred to Al Green’s song “Love and Happiness.” In the aftermath of this historic reconvening, I have been dwelling with how best to communicate to student-readers of African American literature that a great deal can be gained from treating the tradition from a spirit of “love and happiness,” of meaningful, radical joy—even when grappling with weighty texts that refer to dire histories. In other words, I’ve been thinking about ways to embody a Black feminist praxis of loving care and how interpreting in this model need not be a disservice to the seriousness of African American struggles throughout this nation’s history but can be a way of honoring the miraculous, triumphant spirit of persisting through it all. I try to model this heuristic for students through the way we read Black women’s poetry, even and particularly starting with Wheatley Peters (whom June Jordan famously deemed a “miracle”).

After all, although she produced her 1773 book while enslaved and struggled to find success and stability after emancipation, Wheatley Peters nonetheless found sheer joy in the love of and ludic play with the English language imposed on her. We can see in her poems both the heft of the circumstantial constraints binding her and the ways she found small loopholes of retreat, opportunities for reveling pleasurably in signifying on the multiple, polysemous possibilities of meaning language offers. By reclaiming and revising the traditions of Milton and Pope, Wheatley Peters generated poems that have at times been denigrated as mere imitations—but these pieces are far from solely acts of mimicry and instead often show her gifts for a turn of phrase, for enjoying invention.

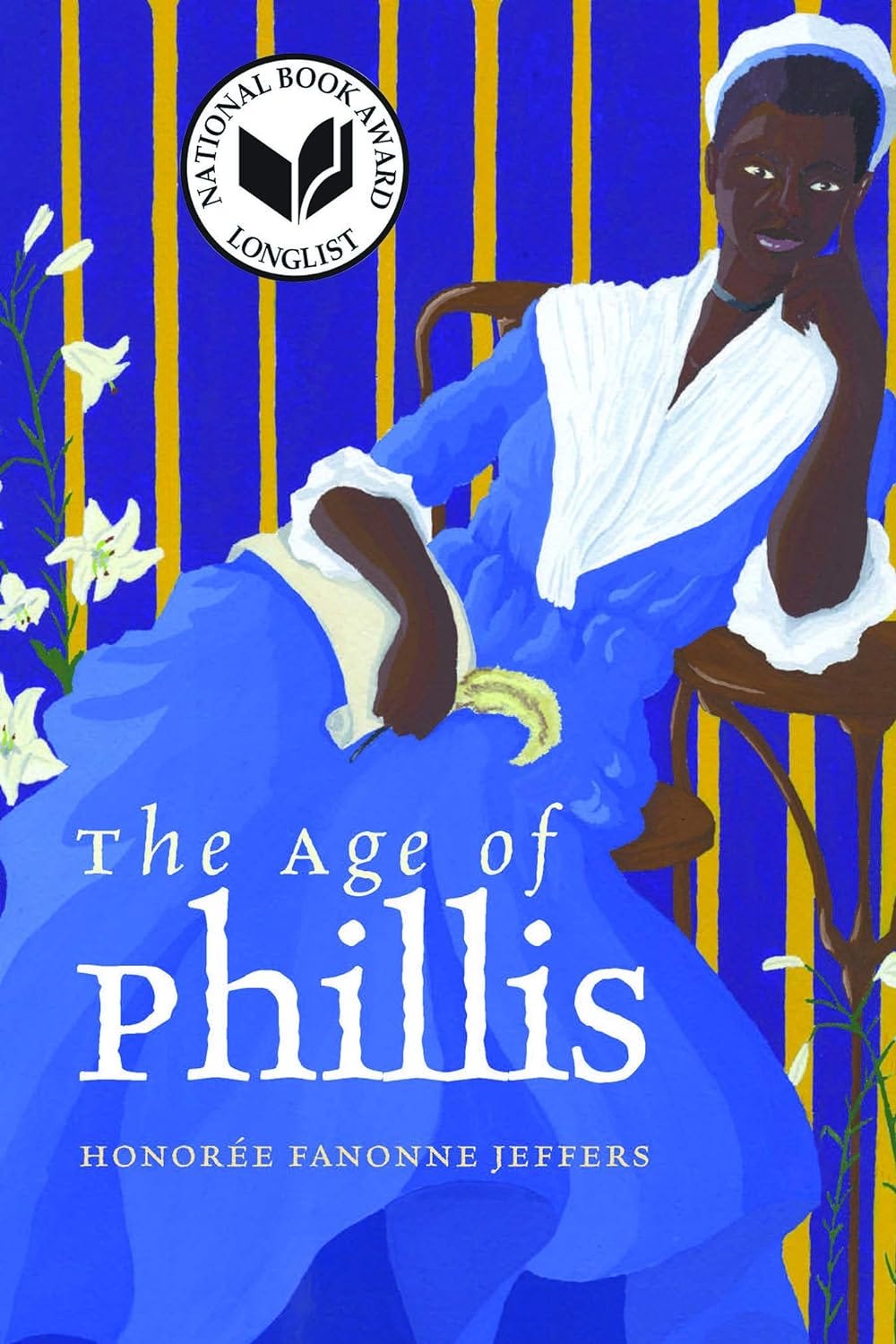

This lens for reading Wheatley (Peters) has motivated countless 21st-century Black poets who write about her, including Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and Evie Shockley (to name just a few). In this spirit of “love and happiness,” I want to encourage readers to consider revisiting together some of Wheatley Peters’s work (perhaps a poem like “On Imagination” or “On Virtue”) alongside some of the contemporary pieces written about her that extend the spirit of lucid, ludic wordplay and unfurl through delighting in the sheer pleasure of punning that (I believe) we see beneath the surface of Wheatley Peters’s writing.

As a special recommendation, you might take up Evie Shockley’s recent 2023 collection suddenly we. This exceptional, moving text contains just one mention of Wheatley Peters but is suffused with and asks readers to share the paradoxical energy I am describing: how Black women writers excel at operating in the tense, liminal, simultaneous space of writing about unconscionably difficult subjects (here, topics like the gun violence epidemic) while seeking joy, delight, pleasure in language itself (and in honoring the rich legacy of Black women who have come before in engaging this work). In one poem, “holla,” Wheatley Peters appears briefly but prominently halfway through, in lines redolent with Shockley’s signature punning: “SING, MUSE / OF THE WRATH OF A PHILLIS, pentameting / all over your i-ams.” Shockley aligns Wheatley with the heft of the epic tradition and also alludes to her stylistic deftness, her ability to manipulate iambic pentameter to her own whims to dismantle and rewrite the terms of first-person lyric belonging, a whole literary tradition summoned up via the succinct pun “i-ams.”

Among the many living Black poets whose work I teach (and value as instructive guiding stars for persisting in combatting the injustices of our white supremacist, heteropatriarchal culture), Evie Shockley is one especially exemplary, simultaneously accessible yet richly elusive/allusive author whom I return to recurrently. To listen to Black women like her requires recognizing difficulties but also reading and hearing in a spirit of meaningful, deep-seated “love and happiness,” the sort that would be extended to all. And time-traveling throughout the rich regenerations of Black poetic legacies helps us see how that spirit persists, survives, and thrives—inspiring us to do the same as we aim to find ways to redress the continuing misogyny (and misogynoir) of American culture and institutions.

Thanks for reading, from Laura’s fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Many now dub her Phillis Wheatley Peters, a gesture that aptly honors the choice she made as a free woman to use her married last name. (Interested readers should consult the work of poet-scholar Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, who has written compellingly about this in many contexts, including in The Age of Phillis.) As it was a fiftieth-anniversary honoring of the 1973 event, this festival’s title maintained the name under which she has long been canonized and by which 1973 participants referred to her.

I want to urge anyone interested in this event and African American literature to read the recent loving, meticulous, elegant biography by towering scholar Maryemma Graham, The House Where My Soul Lives: The Life of Margaret Walker.

Thank you, Laura. I've always responded to the sheer joy in Wheatley's poetry. My favorite is "Thoughts On the Works of Providence," which ends with Reason and Love embracing. Also love the image in that poem of Phoebus making Creation smile at sunrise. I often think of that on days when I feel less joyful, that every sunrise is Nature grinning and inviting me to do the same.

Laura: You convey the energy and solidarity and hope of the Wheatley festival beautifully. Thank you for sharing the image of so many powerful women gathering to speak of joy. I am eager to check out these books!