Not Back to the Future, but Forward to the Past

Wrapping up the *Emma* Challenge, in three parts. Part 2.

Click here for part 1.

When last I left you, dear reader, I was in the midst of a quandary. With the beginning of term only a few days away, I was still without an organizing principle for my English Literature survey course. I could have taken the easy road and just dusted off an old syllabus, but I was determined to try something radically different this time, something that would overturn the traditional march through the years from the Middle Ages to 1800.

I had already decided to challenge that tradition by beginning at the end of the period—or, rather, beyond the end of the period with Jane Austen’s Emma, which dates from 1816.1 I made this decision because students are mostly familiar with the narrative and literary conventions of the novel as a form (even if they don’t yet recognize them as such), and so Emma would give us a baseline. If a text does not behave like a novel, then what are the differences? What are the implications of these difference for the intended audience, cultural context, aesthetic values, etc.? In order to ask these valuable questions, we have to establish the familiar conventions of the novel as a sort of “control group.” And Emma is the perfect choice to set these standards because Austen essentially invented many of these conventions and deployed them as deftly as anyone ever has.

But once you have established this beginning, where do you go from there? Do you press rewind and jolt us back to the beginning of the chronology marked by the course description, say, to Beowulf? It’s hard to imagine a text more radically different from Emma. But perhaps the differences are so great as to make them essentially incomparable, at least to start with. The shift would be disorienting, like shifting from Mozart to Metallica, or from Succession to Sophocles. Actually, that last one may not be such a big shift—I’ll stick with Mozart to Metallica.

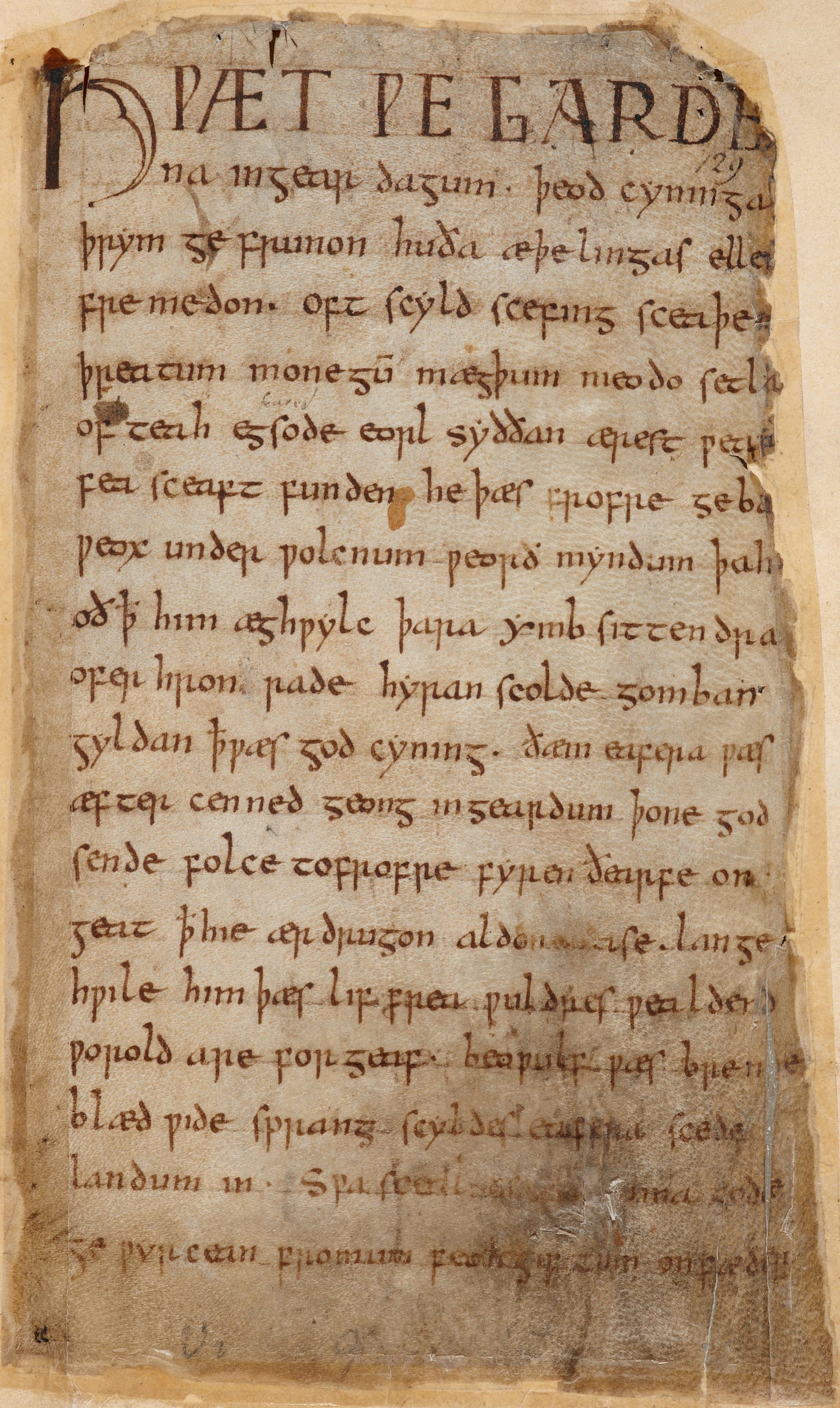

Imagine going from this . . .

To this . . .

Both awesome! But too big a shift? It’s sort of difficult to compare the two.

What if, instead of making the big leap backwards and then going forwards again, a sort of pedagogical version of Back to the Future, we find a text from the century before Austen’s novel—perhaps a narrative that is not itself a novel but that is from a cultural space not quite so radically different as Beowulf would be? We can still use Doc’s DeLorean, but let’s take it back, say, a few decades rather than a few centuries—let’s take it “forward to the past.” So instead of going from Emma to Beowulf, what if we went from Emma to Gulliver’s Travels, and then from Gulliver’s Travels to Paradise Lost, etc. What if we took the whole semester chronologically backwards?

Stay with me for a minute. Gulliver’s Travels, like Emma, is a prose narrative, but it is different from Emma formally (it’s not a novel in the modern sense of the word), as well as tonally and thematically. This gives us a chance to consider these differences and their implications for intended readerships, ideas of gender and domesticity, and literary techniques. Swift uses a highly ironized first person, while Austen uses third person with generous dollops of free-indirect discourse. They both use irony and satire but in radically different ways. What are the effects of these differences? How do the two texts differ in terms of in characterological interiority? In terms of cultural commentary? How are these differing approaches expressed?

After that, let’s go from Gulliver’s Travels (eighteenth century) to Paradise Lost (second half of the seventeenth century). Now we move from narrative prose to narrative poetry. Why? Why does Swift choose prose and Milton verse?

To the modern reader, Austen is more accessible than Swift, who is more accessible than Milton. With each step along the way, we stop to ask why this is the case.

Then, let’s go from Paradise Lost to Twelfth Night—from epic to drama, going back about sixty years.

You see the pattern. With each step backwards, the territory becomes a bit less familiar, a bit more difficult. (OK, I admit, you could argue that Paradise Lost is more difficult than Twelfth Night even though it’s later, but let’s not split hairs.)

We can do the same with non-narrative forms. For example, while we are reading Emma we can also read some of Wordsworth’s poetry. Wordsworth’s poetic mode is still quite familiar to us in our time. But then, when we go backwards to the eighteenth-century poets, like Gray and Pope, we can see what Wordsworth is reacting against. We can see how different the aesthetics of eighteenth-century poetry were from Wordsworth’s, and from our own. Then we can go back to the previous century, to the poems of John Donne and Ben Jonson and Mary Wroth. With each step back, we have a baseline against which we can compare the unfamiliar aspects of the older poems. We can also see how the narrative and non-narrative texts talk to each other. (This can work to great effect, for example, when we look at Twelfth Night next to Shakespeare’s own sonnets.)

Now we’re cooking with gas.

We are not trying to cover everything. We are not trying to march through history chronologically, one damned thing after another. Instead, we are building with each step on what we know, on the familiar. This is analogous to how the study of mathematics works: you begin with more familiar and intuitive operations (algebra, geometry) and then move to the less familiar, perhaps the less intuitive (trigonometry, calculus). The analogy isn’t perfect, because in literature we are not necessarily moving towards more complexity as we move backwards through time, but simply towards less familiar territory.

When we finally do make it back to Beowulf, our final text of the term, we have reached alien lands indeed.2 The poem begins:

Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum,

þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

In Seamus Heaney’s translation:

So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by

And the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness.

We have heard of those princes’ heroic campaigns.

Obviously, this is unfamiliar language. The “we” in the first line of the original (the third line of the translation) obviously does not include us as twenty-first-century readers. We probably have not heard of these Spear-Danes. We have no idea. Even the language itself is alien. We have reached a very unfamiliar place, but we have gotten here iteratively, and the poem perhaps seems less intimidating than it would have been if we had started here in week one of the semester. We are now seasoned readers of the progressively unfamiliar. As things get curiouser and curiouser (to paraphrase Alice), we remain curious. We have surmounted the challenges of Milton, Shakespeare, Chaucer, etc., and now we are ready for the radically alien aesthetic of Old English poetry.

In part 3, we will refocus on Emma itself, how it fits into the course, and how the students respond to it.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Thanks to

, who reminded me of the concept of the “long 18th century,” which would certainly include Emma. So now, if anyone ever complains about the course not matching the course description, I have this answer ready.

A big part of media history is understanding the reception of the work after its initial publication (Was it reviewed positively? Did it sell a lot of copies? If a play, was it widely staged?) vis-a-vis how the work is regarded today, if it is regarded in public at all. In some cases, the work will be seen today in a more positive light than it was initially, whereas in others the reverse will be true because it has dated so badly. Given that Austen's posthumous fame has endured for far longer than the likely more limited reception she received in her lifetime, this is an important strand of understanding her enduring importance.

Amazingly marvelous. Your range astounds.