Dear reader,

Thank you for following me on this strange journey. Please note that this week’s post dives right in without an introduction and assumes that you have read the first two installments. For your convenience, I link them here:

I have enjoyed writing these pieces, and they have sent me down twin rabbit holes of the sagas’ bibliography and Prince’s discography when I should have been doing other work. There is no wasted reading or listening, however, and I’m sure that I will return to both of these subjects in the future. They are inexhaustibly rich.

Yours,

John

I was dreaming when I wrote this,

so sue me if I go too fast.

But life is just a party,

and parties weren't meant to last.

War is all around us,

my mind says prepare to fight,

so if I gotta die

I'm gonna listen to my body tonight.

—Prince, from “1999”

I awoke early

to heap my words;

as a servant of speech

I did my morning’s work.

I have piled a mound

of praise that long

will stand without crumbling

in poetry’s field. (Page 183)

—Egil Skallagrimson1

While not as strident in its Christian perspective as other sagas, such as Njal’s Saga or Laxdaela Saga, Egil’s Saga presents a protagonist who lacks what the author sees as the Christian revelation. Unlike Beowulf, who seems to live in a pre-Christian Scandinavia, Egil is aware of Christianity and even wears the cross when he fights for the English king Athelstan at the Battle of Wen Heath, where his brother Thorolf dies. But despite this exposure to the new faith, Egil continues to follow Odin, who has, after all, given him his gift for poetry.

As we discussed in last week’s installment, however, that gift is not entirely sufficient, as Egil confronts the deaths of his sons, the infirmities of old age, and the changing world around him:

Time seems long in passing

as I lie alone,

a senile old man

on the downy bed.

My legs are two

frigid widows,

those women

need some flame. (Page 202)

His last act before he dies is to take the treasure given to him by King Athelstan and hide it where no one will ever find it. By this point, he is blind, and so in order to dispose of the treasure, he takes two slaves with him. Egil returns from this venture, but neither the treasure nor the slaves are ever seen again.

The saga does not evangelize, but it does juxtapose Egil’s selfish acquisitiveness against the upright behavior of his surviving son, Thorstein, who converts to Christianity and is a “devout and orderly man” who lives to an old age, builds a church, and fathers a great family (page 204). Egil does not value Thorstein as he did his two sons whose deaths he mourns in Sonnetorek, apparently because Thorstein is not like him, either in physical stature or in demeanor.

For the purposes of this discussion, however, I am less interested in the implicit Christian message of the saga than in Egil’s failure to follow the mandates of his own poetic wisdom—unlike the Prince of Purple Rain.

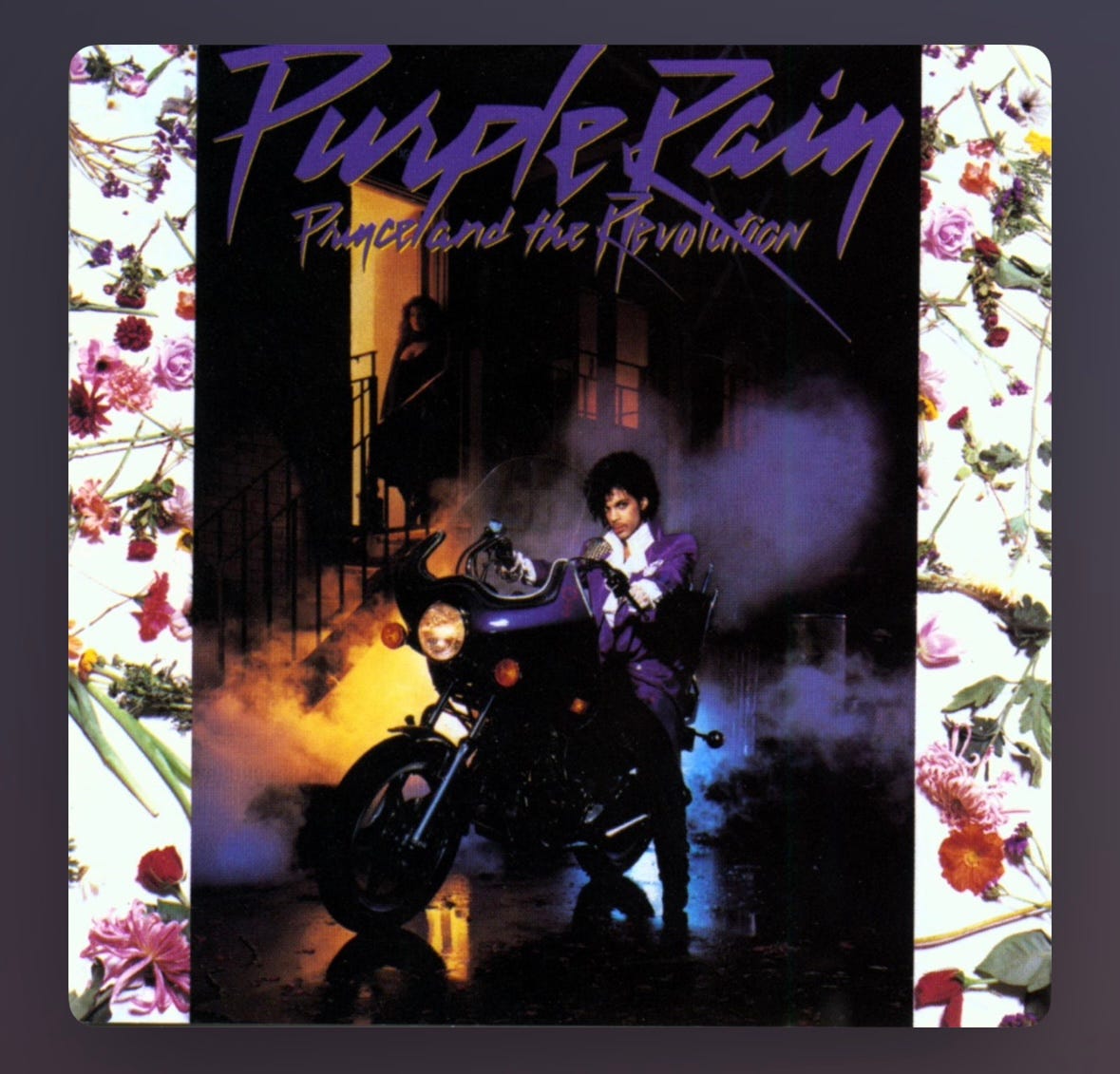

Like Egil’s Saga, Purple Rain is an implicitly Christian text. In fact, one might even call it explicitly Christian, though when I was fifteen years old, I totally missed that aspect of the album—which is partly the point. As with Egil’s Saga, I am less interested in the Christian “message” of the album than with the psychological and artistic journey of the listening experience, which, as I see it, is structured by the record’s two sides (for this was back when albums had sides).

Side One: Apocalypticism and the Descent into Self

As we discussed in the first installment, Purple Rain begins with a spirited and defiant response to the problem of mortality: “Let’s Go Crazy.” Like “1999” from the previous album (see above), the song embraces the wildness of the body and insists that you “better live now / before the grim reaper comes knocking on your door.” The rest of side one reveals a misguided attempt, or series of attempts, to follow this advice. The protagonist embraces the wildness of his desire, but without regard for the needs of others.

“Take Me with You” comes next, and it may be the most beautifully arranged track on the record, with Bobby Z’s tumbling drum fills, the propulsive strings framing the verses, and the gorgeous vocal harmonies. It’s a song filled with longing, anticipated by the introduction, which works through ambiguous chords, searching for a tonal center, before settling into a key when the strings come in—at which point, the singer begins to express a desire for inclusion, both sexual and social, without regard for anything else:

I don’t care where we go,

I don’t care what we do,

I don’t care, pretty baby,

Just take me with you.

This may remind the reader of the young Egil, who wants to go with his older brother Thorolf on his journey and sabotages the trip when he is not invited. While it is a sweet song, it is also a self-centered one, as the growing intensity of desire, signaled by the piling up of vocal harmonies in the last chorus, suggests a fear of being excluded, which is underscored by the final return of those ambiguous chords from the beginning of the song.

That self-centered trajectory continues into “The Beautiful Ones,” which at first seems almost angelic, as Prince woos his beloved in his alluring falsetto, accompanied by delicate piano and synth parts. But it soon becomes clear that this is a desire marked by intense jealousy and a need for possession, as the falsetto turns into a desperate, primal scream: “I want you!” His assurance that he wants to “please you, baby” is belied by the sheer pain of his cry. Bodily desire and possession are all that matter as the song comes to a close.

What follows is the darkest part of the album, the sequence of “Computer Blue” and “Darling Nikki” that ends side one. For me in 1984, it was both mesmerizing and troubling, a glimpse into an adult world of complicated and dangerous sexuality. Canadian comedian Ian Boothby, who is close to my age, has spoken about 1984 as the year when “Prince ruined Christmas.” Having received the album as a gift and without knowing what was coming, he proceeded to play “Darling Nikki” in the presence of his grandmother.

“Computer Blue” begins with the unforgettable dialogue between keyboardist Lisa Coleman and guitarist Wendy Melvoin:

“Wendy?”

“Yes, Lisa?”

“Is the water warm enough?”

“Yes, Lisa.”

“Shall we begin?”

“Yes, Lisa.”

As a teenager, I had no idea what process they were about to begin, but I really wanted to know. Whatever it was, it must have been incredibly sexy. When Prince enters the song, however, he is bereft: “Where is my love life? Where can it be?” We have moved from the selfish desire of “The Beautiful Ones” to self pity, and what follows is a surrender to sensual experience without even the pretense of anything deeper:

Knew a girl named Nikki,

I guess you could say she was a sex fiend,

met her in a hotel lobby

masturbating with a magazine.

Note that the syntax here does not make it clear who is doing the masturbating, Nikki or the singer, and this is fitting, since both of them pursue their one-night stand without regard for the other person—a kind of supercharged mutual onanism. The sex is transactional: “She said, ‘sign your name on the dotted line,’ / the lights went out, / and Nikki started to grind.” This is confirmed when the singer wakes up alone, with Nikki’s note on the stairs encouraging him to “call me up whenever you want to grind.”

We are left with the singer screaming: “Come back, Nikki! Come back!” But he is alone, sexually sated but devoid of the inclusion that he had longed for in “Take Me with You.”

What follows is a strange coda, a bit of “backwards masking.” Those of you who did not live through the early eighties missed all of the parental alarm regarding “satanic messages” that allegedly revealed themselves when rock songs were played backwards. When I was fifteen, I had no idea what the backwards bit said when played forwards. It turns out, hilariously, that it reveals that “the Lord is coming soon,” in a bit of fun at the expense of those overprotective parents.

However, this also marks a return of the apocalyptic message from “Let’s Go Crazy,” a timely reminder as our singer has reached his long, dark night of the soul, alone with nothing but his desire.

As the backward vocals play, we hear the sound of rain. What color is it?

Side Two: I’m a Dove

As we discussed last week, after Egil finishes composing his poem mourning the death of his sons, he is briefly consoled, as his poetry provides the means through which he can “gladly await” his own death. However, Egil fails to follow the advice of his own poetry. Instead of facing his coming death bravely, he sinks into self pity. In his old age, he is surrounded by his friends and family, who love and revere him, but they figure in his late poetry not at all. Instead, his last verses are all about the misery of his failing health, as he strives to make sure that no one else will ever have access to his treasure.

“When Doves Cry,” which opens side two of Purple Rain, is a turning point. Our protagonist may continue to descend into material desire and cynical selfishness, like Egil, which seems to be where he is headed at the end of side one.

As I described in the first installment, “When Doves Cry” was the first single from the album and was the only song from it that I heard for a few months in the summer of 1984. When I finally got my hands on the album, however, I discovered that the version that I had heard on the radio shortchanged the listener by more than two minutes, as the edit faded out with the guitar solo after the last verse. The album version, on the other hand, is a magnum opus of pop, culminating in an instrumental and vocal ecstasy, marked by a keyboard run worthy of a Bach toccata.

Once again, we are concerned with bodily desire and our animal natures: “animals strike curious poses, / they feel the heat, the heat between me and you.” The difference here is that the singer now recognizes the mutual lack of empathy despite their mutual desire: “Why do we scream at each other? / This is what it sounds like when doves cry.”

The other thing that we missed in the radio edit was the concluding attempt at reconciliation and compassion: as the keyboard run ascends to the heavens, Prince repeats: “Darling, don’t cry,” as we end in a minor key. This song sounds like nothing else (note the absence of a bass line) and continues to astonish forty years later, as does the classic video, which includes clips from the film:

The next song is the clearest expression of the album’s Christian message that one does not have to play backwards. Indeed, Prince seems to be singing in the persona of Christ in “I Would Die 4 U”:

You’re just a sinner, I am told

I’ll be a fire when you’re cold,

make you happy when when you’re sad,

make you good when you are bad.

I’m not human, I’m a dove,

I’m your conscience, I am love,

And all I really need

is to know that you believe,

I would die for you,

Darling, if you want me to.

Once again, in 1984, I was completely oblivious of the fairly clear suggestion of Christ’s self-sacrifice here. The crying doves of the previous song have become the Holy Spirit: “I’m a dove.”

But also once again, I’m more interested in the trajectory here than in the implicit Christian message: we move from utter selfishness at the end of side one, through self-awareness in “When Doves Cry” to self-sacrifice in “I Would Die 4 U.” Unlike Egil, Prince turns from his obsession with his own desires to selfless love as the album comes to a close.

Furthermore, unlike Egil, Prince follows the advice of his own art. While Egil renounces the god who has given him the gift of poetry, Prince embraces that divine gift. In the next song, “Baby I’m a Star,” he seems to acknowledge the profundity of his genius, which was clear to all of us who followed his career: “Everybody says, nothing comes too easy, / but when you’ve got it, baby, nothing comes too hard.”

And this brings us to “Purple Rain,” which closes the album. While the song is clearly another expression of compassionate love, the question remains: what is the “purple rain” that we are laughing in, that we are bathing in, that he is guiding us through?

Prince apparently considered purple rain as a sign of the apocalypse, which was forecast at the beginning of the album and which the faithful should celebrate and not fear. The performance of the song that I link to below from Paisley Park in 1999 supports this reading.2

However, this intended meaning need not exclude those of us who do not share Prince’s apocalyptic beliefs. Indeed, I don’t think that this interpretation represents the experience of the song for most listeners, or at least it doesn’t for this listener.

For me, purple rain is the art. It is Prince’s gift to us and to the world. It is art that can reveal our animal natures to ourselves and console us in the face of our mortality. We experience consolation, but we cannot rationalize or explain it. This is why the song concludes not with lyrics, but with the eloquence of Prince’s guitar and his wild, wordless singing (a dove?): the consolation of art, of sublimity, lies beyond precise expression. It lies in its wildness.

What can Purple Rain and Egil’s Saga teach us when we read them together? Both texts embrace an aesthetics of wildness, as well as our animal, bodily natures, and both texts convey these aesthetics through profound and ecstatic artistic expression. However, they offer two possible responses of the artist when facing the inevitability of death. Egil responds by withdrawing into himself. It is important to point out that this is not the saga’s response to death, but rather Egil’s, and that the saga implicitly criticizes this response by presenting the devout and responsible Thorstein as an alternative to his father.

Prince, on the other hand, turns the aesthetics of wildness into a generous overflowing of art. Let him guide you through the purple rain.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet carrier pigeon (or dove) to yours.

Quotations are from Egil’s Saga. Trans. Bernard Scudder. London: Penguin, 2002.

See Alex Harris’s piece on the origins of the song: https://neonmusic.co.uk/princes-purple-rain-the-story-behind-the-iconic-lyrics/

Thanks to

for this reference.

John, Thanks for this post. My sister-in-law is a singer, and Purple Rain is her favorite cover to perform.

Here's her performing it live recently.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nGF7pyu2LUw

John, Helped me understand. Restacked.