The Wife of Bath and the History of Violence Against Women

The Chaucer Reading Challenge continues

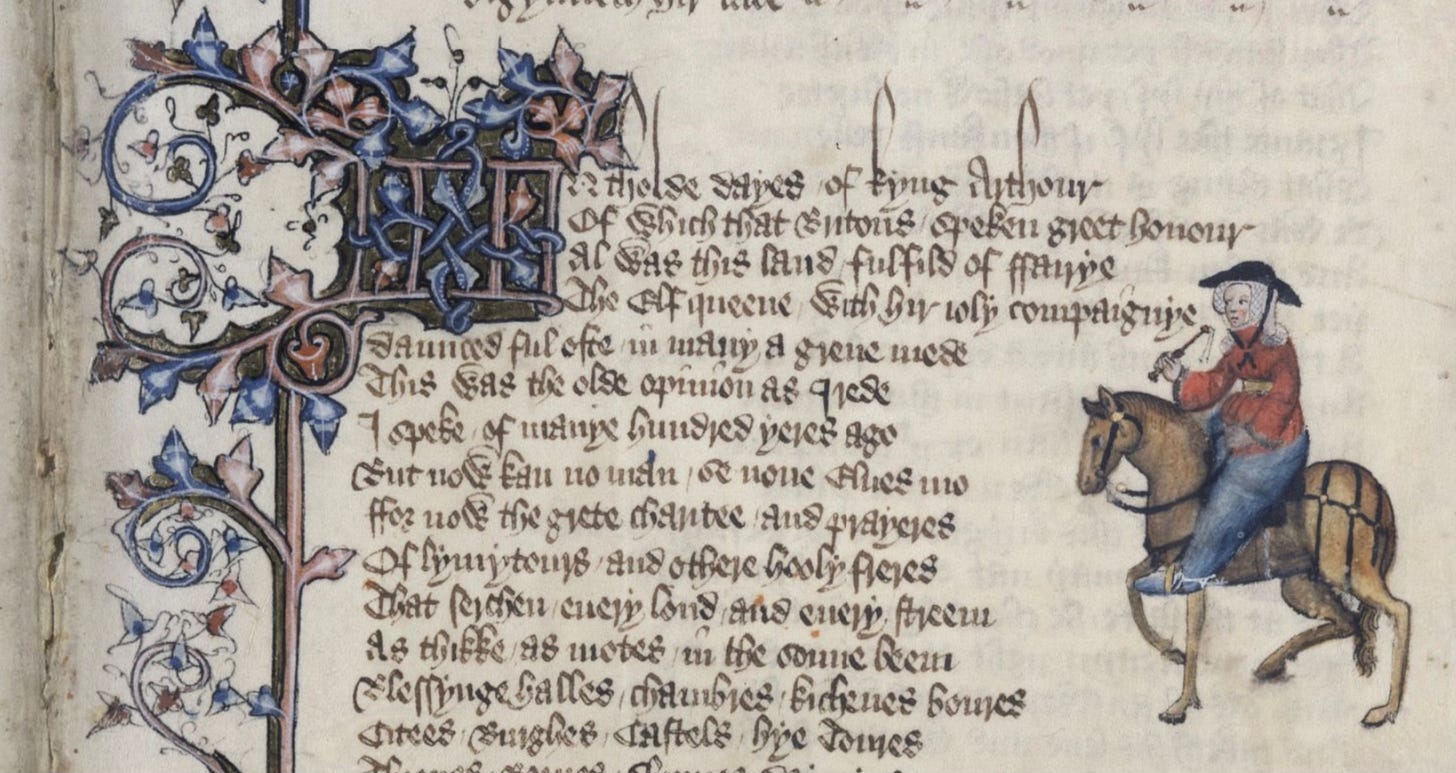

The figure of the Wife of Bath dominates the Canterbury pilgrimage as soon as she takes the stage. She is Chaucer’s most memorable creation, one that has provoked outrage as well as admiration. Chaucerian scholars and undergraduate Chaucer students alike continue a centuries-long debate: is the Wife a proto-feminist model or a misogynist horror show? Where does Chaucer stand on the social position of women?

As usual, you can’t pin him down. But I will leave these questions aside for a moment and point out that it sometimes gets lost in these discussions that the Wife’s discourse, both Prologue and Tale, is at least partly a meditation on violence—on the history of the physical domination of women by men.

The dismissal of this focus on violence by mostly male Chaucerians for much of the twentieth century is astonishing in retrospect. For example, early in the Wife’s Tale, a young knight comes upon a defenseless young woman and rapes her:

And happed that, allone as he was born,

He saugh a maide walking him biforn;

Of which maide anon, maugree hir heed,

By verray force he rafte hir maidenheed (Lines 885-888)

The phrase “allone as he was born” is a common Middle English turn of phrase and here seems to signal that since the knight is alone, he believes himself to be unobserved, and he can, therefore, do as he wishes. However, several manuscripts of the tale provide an alternative reading: “allone as she was born.” If this reading is correct, then it emphasizes the innocence and vulnerable position of the woman. As prominent a figure as W. W. Skeat, the most important Chaucerian editor of the nineteenth century, has preferred this second reading, though most modern editors go with he, since the line appears this way in the most important manuscripts.

In my early-1990s copy of The Riverside Chaucer, considered by most scholars to be the standard edition, a textual note deep in the back of the volume provides the alternative reading of she, along with a list of the manuscripts in which it appears, and adds the comment: “A piece of scribal sentimentality.”

What a bleeding-heart liberal that scribe must have been to feel sympathy for a rape victim!

This bit of editorial misogyny is all the more surprising when we consider the fact that at the time the note was written, Chaucer’s own role in a legal rape case was still in question. In a court document from 1380, when Chaucer was probably in his late thirties, his name appears in relation to a certain Cecily Chaumpaigne. She releases him from responsibility in the case of de raptus meo (“of the rape of me”). What this means has been an electric topic in Chaucer studies for decades. Obviously, many Chaucerians are eager to clear their literary hero of rape charges. What does the word raptus mean in this context? Could it be “abduction,” as some have argued? But what would this mean? And what does it mean that she releases him? Was this a setup? Was she pressured by Chaucer’s powerful friends to drop charges?

For the Riverside editors (or F. N. Robinson, who was responsible for the first two editions of this text) to allow this textual note to remain in print when the Chaucer rape case was still very much a live issue is baffling to us in 2025—though perhaps not surprising, considering the systemic misogyny of the academy for much of the twentieth century and beyond.

As other commentary surrounding the case during the period makes clear, the attitude of the Riverside editors was at one point the rule rather than the exception. The eminent Chaucerian scholar Derek Brewer, for example, comments that all “we can say is that whatever tangled story lies behind this curious document it impeded neither Chaucer’s career nor the regard of his friends.” He goes on to emphasize that his friends were “solid men” and “men of learning,” as if this should help to exonerate the poet.

Elsewhere, Brewer goes even further: “The incident may also suggest the powerful passions which surged within this remarkable man who seems normally to have maintained a genially self-deprecatory unaggressive appearance, and whose poetry, though often satirical, is so free from personal anger.”1

Wow. Stephanie Trigg responds to this brilliantly:

In thus accounting for sexual violence from a man “normally” so genial, Brewer claims the superior knowledge of an intimate friend, as well as normalizing a model of masculine passion and anger that must inevitably find release, especially when the man appears so gentle and passive. It is one of the most threatening passages in Chaucer criticism I have ever come across, and suggests an unusual, darker aspect to the “congeniality” so celebrated in Chaucer studies.2

It turns out that Chaucer was not guilty of rape, as a document unnearthed just a few years ago demonstrated: it was not a rape case at all, but rather a case of a broken contract, in which Cecily left the service of another in order to join Chaucer’s household. (See this article in the New York Times for a summary of the new discovery.)

This new revelation, however, does not change the fact that the boys’ club rushed in with an attempt to obfuscate a history of violence against women, to let Chaucer off the hook before the evidence was in—just as the unnamed knight in The Wife of Bath’s Tale is let off the hook for his crime in the end and is, in fact, rewarded with a beautiful and faithful bride, though he seems really to have learned nothing. The Wife’s insistence, which is reflected in her autobiographical prologue and her tale, that women desire sovereignty in marriage above everything initiates a counter-discourse—both in the text itself, as the Clerk, Merchant, and Franklin offer their alternative views of marriage, and in the history of Chaucerian scholarship.

The counter-discouse is also reflected in medieval readers of Chaucer: the most commonly copied of the tales in the fifteenth century was the Clerk’s, which offers “patient” Griselda, a model of feminine virtue that insists on absolute obedience in marriage despite her husband’s monstrous behavior. It is also reflected in Chaucer’s own short poem “Envoy to Bukton,” which was apparently written for a friend contemplating marriage and which equates the institution with the chain of Satan and suggests that he read the Wife of Bath before going through with it. This may, of course, be ironic—an early example of anti-marriage comic discourse that may remind us of the casual misogyny of twentieth-century comedians on the topics of wives.

But it also returns us to the boys’ club.

I often teach the “Envoy to Bukton” alongside the Wife of Bath, and in the past, students have often laughed at the poem. And it is witty. He begins by saying that he will not say anything against marriage. He will not say that it is the chain of Satan, on which he is forever knawing. But he will say that if Satan were ever to escape from his chain, he would not voluntarily be chained up again.

This semester, however, my students did not laugh. The class is made up entirely of women, and they were not amused. They could tell that they were excluded from the tired old joke. They justifiably refused to appreciate this old chesnut of anti-feminist discourse.

What is remarkable, however, is that Chaucer’s creation in the Wife of Bath is so formidable that she escapes from any attempt to reduce her to a merely parodic figure, as she wrests power away from Jankin, her fifth husband, by responding to his violence with violence. The “Punch and Judy” conclusion to the Wife’s Prologue, in which she and Jankin trade blows, results in her eventual domination of the marriage. After which, she says, they have lived happily ever since. Meanwhile, apparently at odds with her violent impulses, at the center of her tale is a heartfelt meditation on the meaning of gentilesse or gentle behavior that concludes with a prayer for help in living virtuously.

It is a critical commonplace to call her a “modern” figure, but this is not quite accurate. To call her modern because of her pyschological complexity of character is to fall prey to the arrogance of the present. She is certainly a product of her own time, but she also reflects the multi-layered ambivalence of her historical period and of her creator.

Another Chaucerian female character whom some critics have called “modern” is Criseyde, and it is to her that we will turn next time.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

Both of these passages by Brewer are quoted in Stephanie Trigg’s brilliant book Congenial Souls: Reading Chaucer from Medieval to Postmodern (University of Minnesota Press, 2002), pages 36-37.

Trigg, page 37.

I love how you explained the Wife of Bath’s spiel as a “domination” of the pilgrimage. She, in fact, did not remain complacent when telling her outlandish story of feminist values, but held it as a weapon against the others. It is difficult to say whether she is a proto-feminist model or a misogynistic character, because I can truly see both sides. While she seems to pride herself upon her women empowerment mindset, it could come off as misogynistic to some readers. The Wife seems to relay the power of men over women in their society, and her tale seems to miscarry her values stated in her prologue. This hypocrisy within her own writing confuses me on what her point is… Is she telling this story to show that men can be redeemed in the eyes of women?