Tolkien's Ents: Ecology Meets Philology

*The Lord of the Rings* Reading Challenge, week four; plus, a Vaughan Williams update

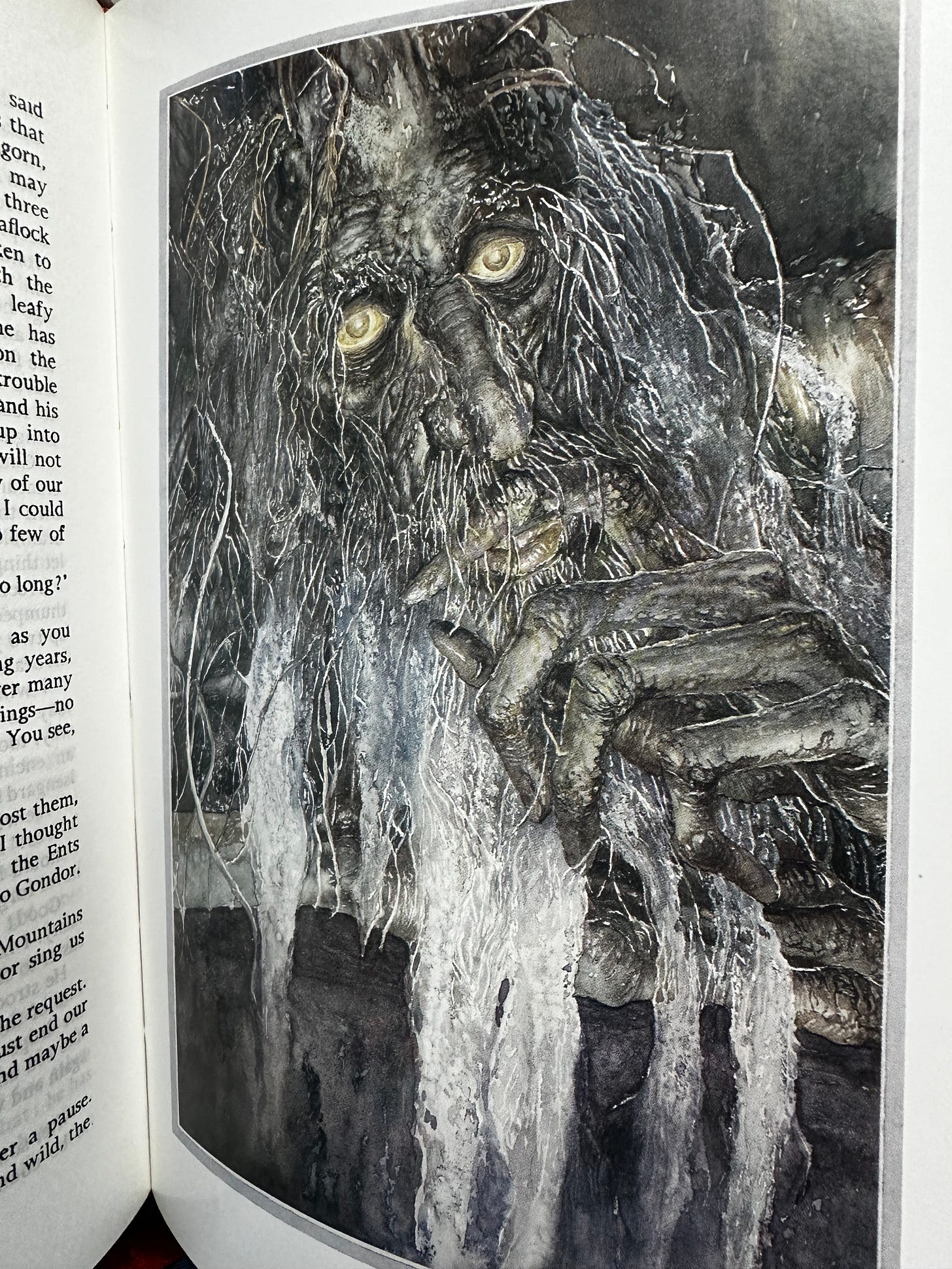

Today, we’re going to talk about everybody’s favorite deciduous character: Treebeard. I think that he is a central figure in LOTR and that he creates the connections that tie together a number of disparate aspects of the text (hobbits, Rohan, Fangorn) and Tolkienian interests (ecology, philology, deep history). I’m going to have to set up these connections fairly methodically, but stick with me; we’ll get there.

Rohan and Philology

Many a precocious undergraduate, having first read Tolkien at the age of ten, comes to a realization in the middle of a medieval literature course: the language of Rohan is Old English! This happened to me, and I thought that I had made a stupendous discovery, only to have my professor inform me that this was common knowledge among medievalists.

Tom Shippey takes this revelation a step further and convincingly demonstrates that not only is the language in question Old English, it is also a specific dialect of Old English, i.e. Mercian.1 The Riders refer to Rohan as "The Mark," which is derived from West Saxon Mearc, which the Mercians themselves would have pronounced "Mark." Tolkien has to construct this dialect mostly through West Saxon, since relatively little of the Mercian survives in written form, but it was the dialect of what would become the English heartland, of the country around Birmingham in his youth and the Oxfordshire of his adulthood.

He was able to perform this reconstruction because of his profession: he was no mere literary medievalist (as I am), but a bona fide, old-fashioned philologist, a vocation which has all but disappeared, having been replaced on the one hand by linguistic studies and on the other by literary studies.

Philologists of the nineteenth century had broken the language code and traced the relationships between what they called the "Indo-European" language groups from Irish to Sanskrit. Furthermore, they had worked their way backwards, tracing changing sound patterns, to construct hypothetical lost languages of the past, like Gothic (some of which did survive in writing) and the "Ur-language" of Proto-Indo-European itself, which may have been spoken in the late Neolithic period and the early Bronze Age. Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is a completely hypothetical reconstruction, because none of it was written down, and it was certainly not a literate culture which spoke it.

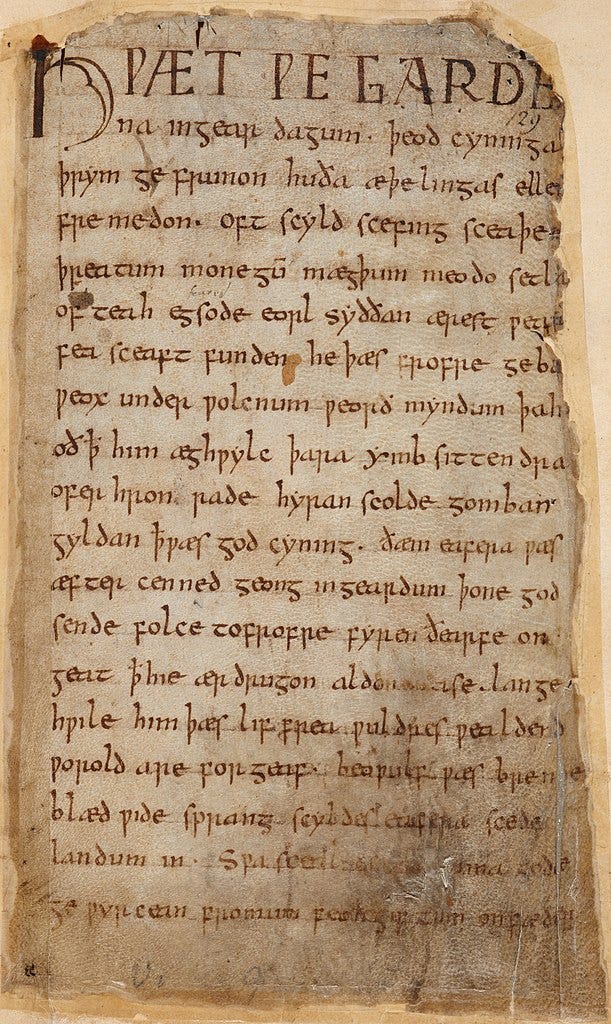

As a product of the nineteenth century, philology inevitably got mixed up with emerging nationalism, in the search for originary national literatures and mythological epics—like Beowulf in English, the sagas in Old Icelandic, the Niebelungenlied in German, and the Kalevala in Finnish (which, incidentally, is one of the few European languages that is not Indo-European, and was also a language that utterly fascinated Tolkien and served as the "aesthetic" basis for his own Quenya language, with its limited consonants and proliferating vowels).

These nationalistic obsessions were, in an historical sense, anachronistic, since the concepts of "nation" and "nationalism" were largely the products of the nineteenth century itself and could not be traced back to the hypothetical languages that philologists were constructing. One imagines that if philology had come into its own in our time, then it would have been used to demonstrate how much we all had in common, as opposed to what made us linguistically distinct. Systematic study of any sort cannot be separated from ideology of one kind or another.

And in fact, these sorts of searches for national ur-texts were largely an exercise in frustration, since most of the evidence was "corrupted" by medieval tendencies towards a unifying Latin Christianity, and because of medieval writers' seeming indifference to the sorts of nationalistic concerns of nineteenth-century scholars. Tolkien explained his response to such frustration in a letter to Milton Waldman in 1951:

I was from early days grieved by the poverty of my own beloved country: it had no stories of its own (bound up with tongue and soil), not of the quality that I sought, and found (as an ingredient) in legends of other lands. (Letters, 203)

He describes this frustration in the context of a long, thorough explanation of his own invented Legendarium, which at some level was an attempt to provide an English mythology, constructed (alas) rather than uncovered or discovered (in, say, a hitherto lost manuscript).

The White Horse

But there was some "uncovering" that went along with his invention, and we see some of this in Rohan. In addition to the language of the Rohirrim, there is their devotion to horses. As Tom Shippey, once again, has pointed out, Rohan's emblem of a white horse in a green field exists in the very soil just a few miles from Tolkien's house: the White Horse of Uffington, a magnificent bronze-age figure cut into the chalk downs. (I made my pilgrimage to the White Horse back in 2007, on the rainiest summer day that you could imagine; I hiked several miles to visit it, along with the nearby Wayland's Smithy, a much older, neolithic site. It was worth getting soaked. I've never been so cold in the month of July, and I warmed myself in a local pub by eating soup and drinking coffee.)

This connection of the White Horse to this location in the Mercian heartland provides a basis for all of the horse-derived names among the Rohirrim, with the element eoh ("horse"): Eowyn, Eomer, etc. The White Horse may have suggested to Tolkien that at one point in the distant past these people had a great reverence for horses, even if it had been forgotten in later years. Rohan’s culture is, therefore, similar to that which we find in Beowulf, with the addition of prominent horses—an imagined, lost horse-centered culture in a hypothetical Mercia, whose traces are literally carved into the land.

Rohan is adjacent to the forest of Fangorn, of which the Rohirrim tell old wives' tales about creatures called ents, as the major river flowing through their land is the Entwash. Here ecology and philology combine to trace an historical-linguistic path through a lost, legendary past of Mercian horse-lords, to a much older culture and language—obscure even to the horsemen—which is completely Tolkien’s invention.

Ents: Philological Origins

Like that of Rohan, this culture is engraved in the English landscape, in the last remnants of old forest remaining in a country that was mostly cleared by the Middle Ages—a culture of beings much like the trees themselves. Ent is a word that Tolkien took from Beowulf. It seems to mean "giant," and the enten are listed with other evil creatures that are associated with the descendants of Cain, along with Grendel. Tolkien rescues the ents from these demonic origins, which, after all, were inflicted on them by the officious Christians who wrote down the poem.

The result is perhaps Tolkien's most remarkably original literary creation: the Ents, the shepherds of the trees. While they clearly reflect his ecological concerns, they are also the aspect of the book that most profoundly connects his twin devotions to ecology and philology. In a sense, the language of the ents is philology, or perhaps more accurately, a language that contains its own philology, in which words correspond directly with the reality of things (rather than the usually arbitrary relationship in language between word and thing). When Merry and Pippin ask Treebeard to tell them his real name, he responds:

For one thing it would take a long while: my name is growing all the time, and I've lived a very long, long time; so my name is like a story. Real names tell you the story of the things they belong to in my language, in the Old Entish as you might say. It is a lovely language, but it takes a very long time to say anything in it, because we do not say anything in it, unless it is worth taking a long time to say, and to listen to. (465)

Here is the real dream of Tolkien's version of philology: if you go back far enough, if you trace language back to ultimate origins, you reach a tongue that corresponds precisely to reality, a pure language spoken by the very land, uncorrupted by ages of abuse visited upon both the land and the language. Of course, Tolkien knew that this dream was impossible, so he brought it to life with Treebeard.

Like the elves in Lothlórien (as we discussed last week), Treebeard provides a memory of time that is beyond even the historical records of humans, a memory which goes back to a time when the woods of Fangorn "were like the woods of Lothlórien, only thicker, stronger, younger. And the smell of the air! I used to spend a week just breathing" (469). As the language evolves with the story of land, it expands without regard for the human sense of time. Treebeard is amused by the word hill, because "it is a hasty word for a thing that has stood here ever since this part of the world was shaped" (466). He provides only a part of his word for it: a-lalla-lalla-rumba-kamanda-lind-or-burúmë (465).

This kind of language may remind us of the medieval notion of the world as a living text, written by God, but it also corresponds to more modern scholarly and scientific disciplines—cartography, geology, environmental history—which attempt to make ecology legible. The ents inscribe not only the forest and the landscape into their language, but also the “lore of living creatures”—their descriptive lists of fauna.

Ents and Hobbits: Old Connects to New

The absence of hobbits from these lists confuses Treebeard, and their subsequent incorporation of them into Entish lore is a moment of more profound significance in the context of Tolkien’s work than it may appear. In fact, it is a moment that is emblematic of the way in which the hobbits have inserted themselves into the Legendarium.

Hobbits played no role in Tolkien’s mythological world as he first conceived it. He wrote The Hobbit as a children’s story more or less independently of his Legendarium, though mythical elements made cameos, specifically the Mirkwood Elves and Elrond. As Tolkien himself explained in the same 1951 letter:

The Hobbit, which has much more essential life in it, was quite independently conceived: I did not know as I began it that it belonged. But it proved to be the discovery of the completion of the whole, its mode of descent to earth, and merging into “history.” As the high Legends of the beginning [The Silmarillion] are supposed to look at things through Elvish minds, so the middle tale of the Hobbit takes a virtually human point of view—and the last tale [LOTR] blends them. (204)

Treebeard, the most obvious pure philologist in our book, has, likewise, not included the hobbits in his world view until they break into his story and make him notice them. They have not been included in the Old Entish lists with elves, dwarves, ents, and humans:

“We always seem to have got left out of the old lists, and the old stories,” said Merry. “Yet we’ve been about for quite a long time. We’re hobbits.”

“Why not make a new line?” said Pippin.

“Half-grown hobbits, the hole-dwellers.” (465)

This is Tolkien’s little philological joke. He explains in the Appendices that the word hobbit derives from holbytla, which in Old English (or in the language of Rohan) means “hole-dweller,” which in turn allows us to translate Pippin’s proposed addendum as redundant: “Half-grown hole-dwellers, the hole-dwellers.” Unlike Treebeard, Pippin is not a philologist and does not recognize the meaning embedded in the name of his own kind. (It is fitting, therefore, that when Treebeard gives us the new lines about hobbits for inclusion in the lists, that it is not Pippin’s proposed line that makes it in—though that lies outside this week’s reading, so I won’t quote it. You may find it in Book Three, Chapter 10.)

But it is more than just a joke: the Rohirrim also refer to the hobbits as “holbytla,” which suggests that hobbit language is a “later” form of Rohan’s language—analogous to the relationship between Old English and Modern English. By using names to establish these links between three societies, Tolkien connects the hobbits, the ents, and the people of Rohan, both philologically and ecologically. And just as Treebeard brings the hobbits into his lists, Tolkien brings them into his Legendarium to play their vital roles, to bring about "the completion of the whole," as he himself wrote.

On Friday, I’ll be back with a piece for paid subscribers on Tolkien and race: yes, we have to talk about orcs. Meanwhile, I would love your thoughts on the ents and Rohan. This is a favorite part of the book for many readers, myself included.

Vaughan Williams Listening Challenge

This week, we turn first to RVW's Sixth Symphony, completed after World War II, and many have indeed heard the echoes of war in the music, though the composer never confirmed that this was his intention. The violence of the first movement is followed by a second movement full of dread; the scherzo includes a remarkable solo for tenor saxophone, and the final movement seems to fade away towards death (an association which RVW did confirm). This is completely unlike our previous selections and will give you a sense of his compositional range. There are several good recordings of this symphony; I've chosen a recent one by Antonio Pappano and the London Symphony Orchestra.

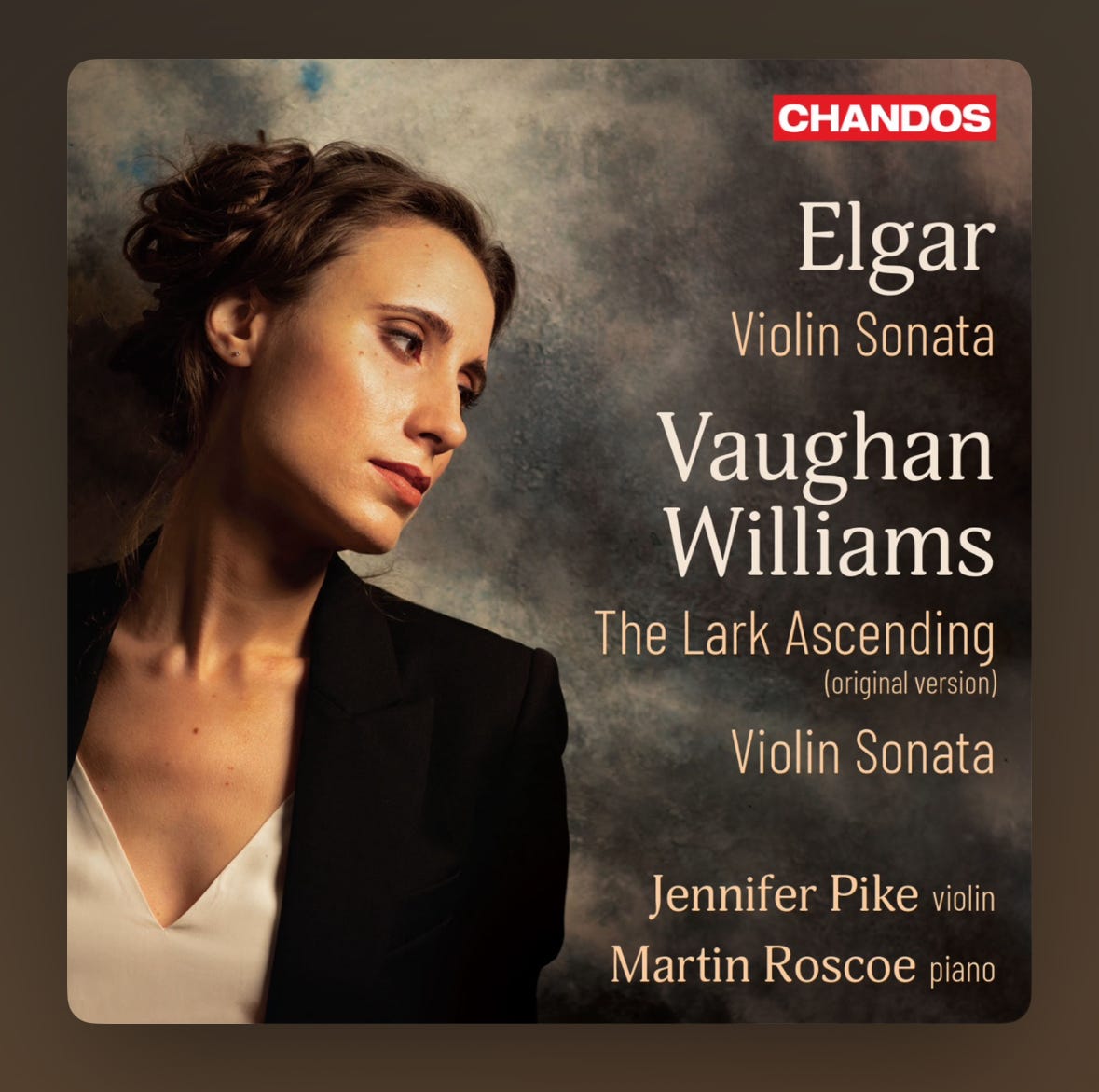

The second piece is perhaps the most often played of any of RVW's works, though not in this version. The Lark Ascending is popular in its version for violin and orchestra, but it was written first for violin and piano, and the latter is what we are listening to this week, played beautifully by Jennifer Pike and Martin Roscoe.

Here are links to the playlist on Apple Music and Spotify:

The RVW Listening Challenge on Apple Music

The RVW Listening Challenge on Spotify

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet ur-language to yours.

See Shippey’s J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, pages 90-97.

I learnt the other day that the white horse has been kept white since the day it was created, through invasion, plague and war, an unbroken lineage of people rechalking its shape and body. How about that? Incredible.

Apart from being a brilliant story, Tolkien's greatest achievement, in my opinion, is his focus on language. No matter how many times I read these stories I continue to be enthralled by the depth of integrated language work Tolkien does. It is really brilliant and shows what an erudite individual he was. It seems to me that his true calling was Philology and he simply used stories as a way to work in his love for language. Great article John. You are really bringing to life some of the lesser-understood aspects of Tolkien's legacy.