In March of 1941, Tolkien wrote a long letter to his son Michael, who was apparently attached to a young woman and contemplating marriage. Many 21st-century readers may be inclined to gasp and shake their heads throughout—so full is the letter of gender essentialism and confident assertions of general “truths” about men and women. For example, on the subject of friendship, he writes:

In this fallen world the “friendship” that should be possible between all human beings, is virtually impossible between man and woman. The devil is endlessly ingenious, and sex is his favorite subject. He is as good every bit at catching you through generous romantic or tender motives, as through baser or more animal ones. This “friendship” has often been tried: one side or the other nearly always fails. Later in life, when sex cools down, it may be possible. It may happen between saints. (66-67)

(St. Augustine has a lot to answer for—especially for his bequeathing of his sexual neurosis to sixteen-hundred years of Christians, but that is a topic for another day.) Many readers have complained of the absence of any female characters from the “Fellowship” that sets out from Rivendell, a group of nine, chosen to represent all of the free people—except, apparently, the half of the population lacking a Y chromosome. But I think that this letter provides Tolkien’s reasons, however dubious they may be: women are essentially excluded from a male “fellowship.” Unlike The Hobbit (from which women of any sort are entirely absent), The Lord of the Rings does feature a handful of female characters, but they are set apart and treated as exceptional in various ways. They may be worshipped and glorified (Goldberry, Arwen, Galadriel); they may yearn to break out of assigned gender roles (Éowyn); or they may be evil (Shelob—though as a spider, she perhaps does not belong to this discussion, but she deserves further discussion at some point).

While biographical criticism is not always helpful, in this case it is appropriate to contextualize Tolkien’s ideology of gender. He lost his father when he was three years old, and he was raised by his mother until she also died, when he was twelve. In a letter from 1955, he credited his mother with his love of languages and literature: “it is to my mother who taught me (until I obtained a scholarship at the ancient Grammar School in Birmingham) that I owe my tastes in philology, especially of Germanic languages, and for romance” (318)

It was also to his mother that he owed his Catholicism. She was essentially ostracized from her family after her conversion to Rome, and at her death she left her two sons in the charge of a priest, Father Francis Morgan, as their guardian. Tolkien seemed to have viewed his mother as saintly and hastened to an early death by persecution for her faith.

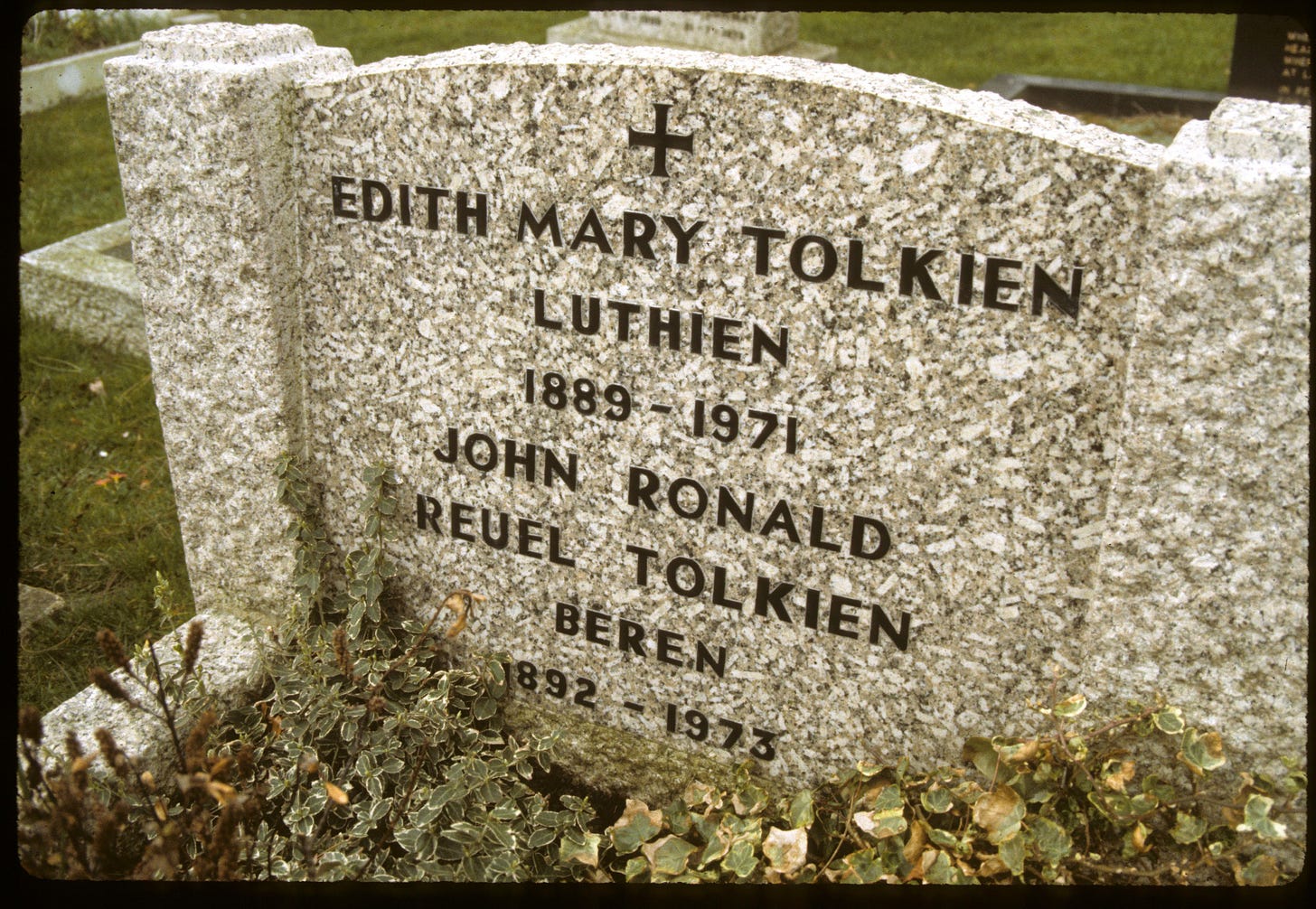

The other significant woman in his early life was his wife, Edith, with whom he fell in love when he was 16. His guardian learned of their romance about a year later and forbade him seeing her. When he turned 21 and was freed from Morgan's guardianship, he immediately wrote to Edith asking her to marry him. They had not seen each other for three years, and Edith was engaged to someone else. Tolkien, however, went to see her in person and convinced her to marry him instead.

A year later, in 1914, after her conversion to Catholicism at Tolkien's insistence, they were married. She gave up a fiancé and a religion for him.

Tolkien's interaction with women had been limited in the ten formative years between the death of his mother in 1904 and his marriage. He had attended an all-boys boarding school before going up to Exeter College, Oxford, which was also all-male. His closest friends were three boys with whom he formed the "Tea Club and Barrovian Society" ("TCBS"), a tightly-bound group dedicated to poetry and to the study of the lost languages and literatures of old Europe. They all remained friends until two TCBS members died in the Great War. When Tolkien announced his and Edith’s engagement to the TCBS, they congratulated him, but their letters were ambivalent and expressed anxiety that the marriage might interfere with their friendships. Throughout his life, Tolkien was drawn to such small, close-knit groups of men, most famously the Inklings at Oxford, which included C. S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Owen Barfield, among others.1

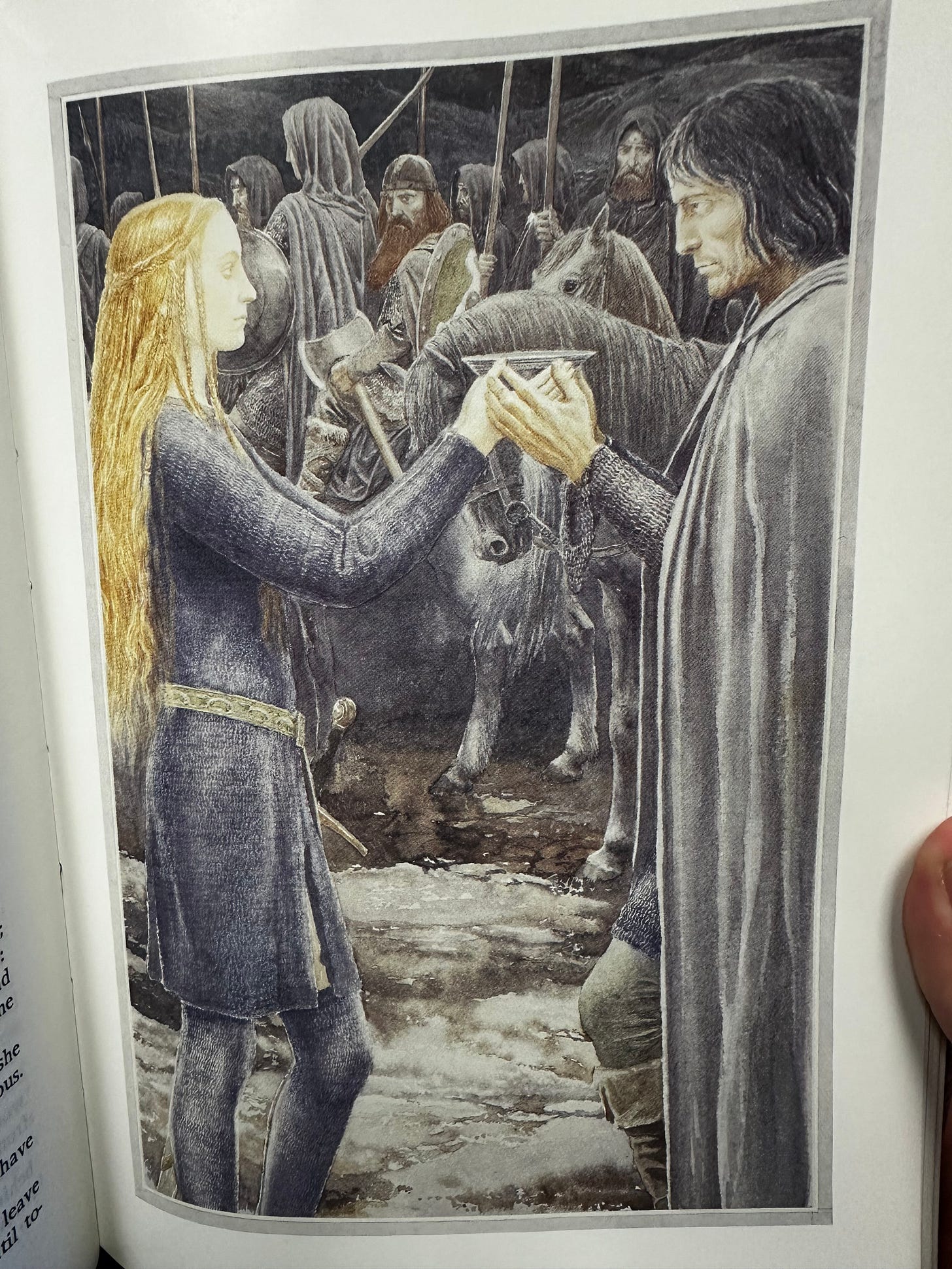

Such powerful, intimate relationships with men clearly inform his fiction, the most telling example being the intense love between Frodo and Sam. Women in his life, on the other hand, were elevated (or relegated) to saintly, self-sacrificing roles of mother and wife—to be admired but not befriended. While he clearly loved Edith, she did not share his literary interests, and so they probably had little interaction regarding the great passionate pursuit of his life. He idealized their relationship in his love story of Beren and Luthian, told in full in the Silmarillion and referred to in LOTR as a model for the betrothal of the mortal Aragorn to the elvish Arwen.

Tolkien's primary social circles, then, were homosocial throughout his life, and while he admired women, he clearly viewed close, non-familial relationships between the sexes as problematic. This homosociality is reflected in LOTR, with female characters set apart in the aforementioned roles occupied by the likes of Galadriel and Goldberry.

This gender essentialism is apparent in all of the narrative strands as we begin The Return of the King. We have just left the homosocial unit (or love triangle?) of Frodo, Sam, and Gollum at the end of The Two Towers. (Note that in Book Four, we follow a single narrative strand, while in Books Three and Five our attention is divided among several). Now in Book Five we turn to three major narrative threads, each of which centers on a homosocial unit. First, there is Gandalf and Pippin (and later Beregond and Bergil) in Minas Tirith; then there is the "grey company" of Aragorn, Legolas, Gimli, and their other (male) companions as they traverse the Paths of the Dead; and finally there is the muster of Rohan, as Théoden and Éomer assemble their mounted troops and ride to Gondor.

"But wait!" the attentive reader protests, "What about Éowyn?"

Well, exactly. Aragorn denies her the opportunity to ride with him, and Théoden assigns her to look after the homestead while he is away. She is able to ride with the Rohirrim only because she disguises herself as "Dernhelm" (Old English for "secret helmet"), and as in a Shakespearean comedy, her drag is completely convincing to everyone, even to Merry, whom she takes along on her horse. Despite Éowyn’s presence, the Rohirrim form a homosocial structure.

I will forebear saying too much about Éowyn here, because we have a superb guest post about her by

coming up in a couple of weeks, but I will say this: her victory over the Lord of the Nazgûl is one of the most powerful moments of the entire book. It moves me to tears, even after four-plus decades of rereading.Is this moment of heroic greatness enough to make up for the relative dearth of interesting female figures in the rest of the book? Probably not.

But one moment between Éowyn and Aragorn may help to explain that lack. When she asks him leave to ride with him to the Paths of the Dead, he responds:

"Your duty is with your people," he answered.

"Too often have I heard of duty," she cried. "But am I not of the House of Eorl, a shieldmaiden and not a dry-nurse? I have waited on faltering feet long enough. Since they falter no longer, it seems, may I not now spend my life as I will?"

"Few may do that with honour," he answered. (784)

In this essentialist universe, those with honor will surrender their freedom in order to do their duty, and for Tolkien these duties are generally divided according to gender. The presence of Éowyn in the narrative, however, demonstrates that he understood that women could be frustrated by traditional roles and also that he believed women to be capable of greatness, even if his fallen nature meant that he couldn't be friends with them.

I'll be back later this week with a bonus post for paid subscribers on Tolkien's vision of war. Here is a link to our reading schedule.

Thanks for reading, from my fancy internet typewriter to yours.

In addition to Tolkien’s letters, I have consulted John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War (Houghton Mifflin, 2003) for accounts of Tolkien’s and Edith’s courtship, the TCBS, and his service in the army during the First World War.

You mention this, John, but I think it's worth spending another moment on it: Tolkien wasn't making up this society of men. He lived it in his own life at boarding schools, university, and in the Great War. Lewis, in Narnia, had the benefit of writing about children. But even he had to deal with Susan's puberty -- not well, I would add, due to being embedded in the same male society.

I've been pondering this one, because it would be so easy for me to ride into battle like Eowyn, crying, "This feminist will not be caged!" You can't read "The Lord of the Rings" without being aware that the patriarchy is baked into every word — yet so it was in Tolkien's time, and it was certainly part of the Middle Ages of Europe on this real earth (and in many other cultures as well). With this third reading of a trilogy I've long loved, despite its flaws, I'm struck by how I inhaled these books even as a girl: I didn't only pine for Aragorn, as Eowyn does; I wanted to *be* him — also like Eowyn, riding to battle. She wants be the hero and creator of her own story, something Tolkien tapped into very well. For that reason alone, he's far from a misogynist. I wonder if he channeled some of his own longings into her character, just as he did with Faramir.

I think Tolkien's essential gentleness is what continues to draw me. The other thing I've been struck with this time around is the power of friendship in his heroic tale, be it between Frodo and Sam, or all four hobbits, or between Gandalf and Bilbo, or Legolas and Gimli. Rather than call it "homosocial," I'd say that feeling of deep connection with and responsibility toward your friends resonates beyond gender. I can imagine myself there without referring to "fellowship" so much as the love of friends, the beauty of it, the sadness of loss and imperfection and incompleteness, even in the stories we tell. It still brings me to tears, and without jumping too much into the conclusion of "The Return of the King," I think it's fair to say "not all tears are an evil."