I was once at the dentist, my mouth wide open and full of dental paraphernalia, when my hygienist launched into a competent recitation of the opening lines of The Canterbury Tales. I think she made it to the “smale foweles” (“little birds”) in the ninth line before stumbling and asking for a cue. I, of course, was in no real position to offer one, since I could barely move my mouth. I made some noises—something like “at eeen ah a ich it owen eeeah.” That was enough for her to continue: “That sleepen al the night with open eye.”

This had stuck with her in the twenty or so years since she had graduated high school, and it speaks to how well Chaucer can resonate with young people when he is taught well. I can’t remember how she knew that I was studying Chaucer. I was a graduate student at the time (this was the late 90s), and it must have come up during a previous visit. In any case, she was quite pleased with her recall, and I was impressed.

Of course, the idea that 21st-century high school students might memorize 18 lines of poetry, let alone in Middle English, is a non-starter. [Old man yells at cloud.]

I’ve thought about those little, singing birds who sleep all night with an eye open in the years since. It’s significant, I think, that the first “sound” that we “hear” in the Tales is birdsong. This is especially the case if we think of writing as a sort of sound-recording device—the best available before the invention of the phonograph. Birds continue to play important roles at several key moments in the Canterbury sequence, concluding with The Manciple’s Tale (the final narrative tale, since The Parson’s Tale is not a narrative but rather a sort of guidebook for confession).

I should correct myself: birdsong is the first sound made by a living creature in the Tales, because there is, of course, the rain (“shoures soote”) and the wind (Zephyrus). This sequence—rain, wind, birdsong—is interesting, because at the end of The Manciple’s Tale, the crow is deprived of its power of song and cast out into the elements—the wind and the rain—thus bracketing the narrative space of the Tales with these three sounds. I have argued elsewhere that this bracketing of the Canterbury narrative with the initiation and curtailment of birdsong creates a sort of free space for play—for song—which the Parson brings to an end with his stridently anti-narrative sermonizing.1

This opening up of a space for play allows us to move into the fictional mode of the frame narrative—self-consciously fictional, as we discussed last time, because the first-person narrator addresses the reader as if this were something that actually happened to him, though we know that it is not. This series of portraits of pilgrims is, therefore, part of the Chaucerian creation, a product of Chaucer the Maker, as opposed to the divine Maker. (“Maker” is, by the way, a Middle-English word for poet.)

The progression of portraits does, however, mirror a sort of medieval ideal of societal organization, with the Knight (our highest ranking pilgrim) and his entourage (Squire, Yeoman) leading the way, followed by the three representatives of the holy orders (Prioress, Monk, Friar). This conventional ordering, however, does not account for the varying degrees and shades of irony that Chaucer gives us: the Monk who loves hunting and forswears the Order of St. Benedict, the Friar who refuses to associate with the poor, the Prioress who wears questionable jewelry.

As Jill Mann showed us in her classic book on The General Prologue—Chaucer and Medieval Estates Satire—the poet is drawing upon a generic satirical tradition in these portraits. However, as Barbara Nolan has convincingly argued, Chaucer’s innovation here is to allow the narrative voice to take on the voices of the various pilgrims through indirect discourse—more than four centuries before Jane Austen would master this technique.2

When Chaucer describes the Monk, for example, it is clear that our narrator is parroting the Monk’s problematic opinions—his disregard of the monastic order, his contempt for manual labor and intensive study—and then agreeing with them: “And I saide his opinioun was good.” This immediately creates an ironic effect: the intelligent reader will understand that our poet does not approve of the Monk’s pronouncements, even as his first-person narrator celebrates them.

The conventional ordering of the portraits is also not reflected in the ordering of the tales. At first it seems it will be, as the Knight draws the short straw and so tells the first tale—an outcome surely engineered by the Host. But, as we shall see, the Miller unceremoniously interrupts this proper ordering as he insists on “quitting” (“paying back”) The Knight’s Tale in defiance of the Host’s intentions. This challenge to the social order introduces drama to the frame, but it also allows the frame narrative to become an exploration of selfhood and self-representation, as it forces us to read across the various social stations and across from the frame to the individual tales. It allows the Tales to become endlessly dialogical, with its polyphony of voices.

But what about Chaucer’s own self-representation in the form of the narrator? As Nolan observes, there is no portrait of the narrator as there is for the other pilgrims, no passage that begins “A poet ther was.” Instead, we have his rhetorical self-fashioning—the most compelling example of which, at least in The General Prologue—is a passage often referred to by critics as “Chaucer’s Excuse”:

But first I pray yow, of youre curteisye,

That ye n' arette it nat my vileynye,

Thogh that I pleynly speke in this mateere,

To telle yow hir wordes and hir cheere,

Ne thogh I speke hir wordes proprely.

For this ye knowen al so wel as I:

Whoso shal telle a tale after a man,

He moot reherce as ny as evere he kan

Everich a word, if it be in his charge,

Al speke he never so rudeliche and large,

Or ellis he moot telle his tale untrewe,

Or feyne thyng, or fynde wordes newe.

He may nat spare, althogh he were his brother;

He moot as wel seye o word as another.

Crist spak hymself ful brode in hooly writ,

And wel ye woot no vileynye is it.

Eek Plato seith, whoso kan hym rede,

he wordes moote be cosyn to the dede.Also I prey yow to foryeve it me,

Al have I nat set folk in hir degree

Heere in this tale, as that they sholde stonde.

My wit is short, ye may wel understonde. (Lines 725-742)

This is breathtaking—especially in its insistence on the “accuracy” of his account, coupled with his purported lack of confidence in being able to convey it accurately: “My wit is short.” Forgive me, the narrator implores us, if I use plain or even rude language. After all, Christ himself uses plain language in the Gospels, and we have no problem with that. If I don’t provide a faithful retelling of what these pilgrims said, then I will be guilty of dishonesty.

Wow. Once again, the ironic effect is to call attention to the text’s fictional nature and to leave us on unstable epistemological grounds: this is a fictional text that the narrator insists on conveying “proprely” (“accurately”) and yet is unsure about whether or not he can do so.

The ground shifts under our feet, and truth is a slippery fish. Welcome to the Chaucerian universe.

This Week’s Medieval Music: Machaut

Guillaume de Machaut was Chaucer’s much older French contemporary, having been born forty years before the English poet. He was among the last poets to set his own words to music in the troubadour tradition, though he also wrote sacred music. This week’s album, performed by The Orlando Consort, is a collection of secular songs in four parts. These songs are all well preserved, unusually so for medieval music, in lavishly beautiful manuscripts. This makes this music special for our purposes, since it is very likely that Chaucer and his social circle heard much of it and that what we hear in the recording is reasonably close to what it would have sounded like in the fourteenth century. Most performances of medieval music must be educated hypotheses, but here we have a better textual evidence and thus can be more confident with regard to performance practices.

Our medieval music in the coming weeks will range far afield of Chaucer’s own time and place, but this music was part of Chaucer’s world.

Here is our playlist on Apple Music

Here is our playlist on Spotify

In the next installment we will move on to The Knight’s Tale. And don’t worry if you wanted more discussion of the individual portraits in The General Prologue. We will take a look at several of those when we reach their individual tales.

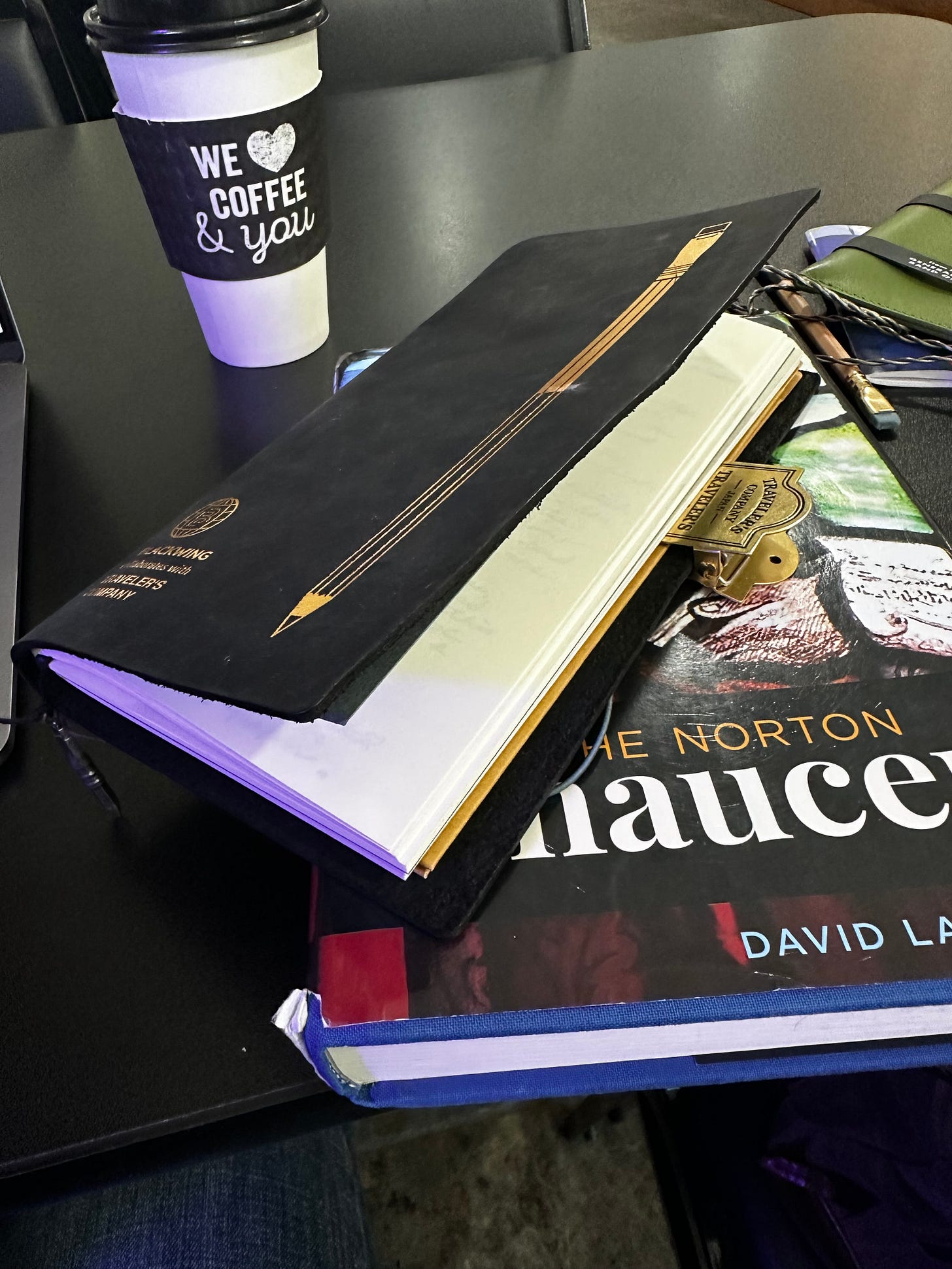

Meanwhile, thanks for reading, from my fancy internet notebook to yours.

I made this claim in “Bird Sounds and the Framing of The Canterbury Tales." Essays in Medieval Studies 33 (2018): 1-9. As far as I know, I am the first to make this argument, which is astonishing to me, since I think it seems fairly obvious.

Nolan, “‘A Poet Ther Was’: Chaucer's Voices in the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales.” PMLA , Mar., 1986, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Mar., 1986): 154-169.

Thank you for this John. I don't think I could attempt this reading without you. The social order is interesting - the knight and entourage and then the three religious people next. Whereas the most virtuous religious person, the parson, appears down the list... But then he receives the distinction of getting the final word in the tales.

Interesting - the early (and final) appearance of birds marking a free space for play. It reminded me of the appearance of a lark in the first few lines of both 'Mrs Dalloway' and 'To the Lighthouse' (I happen to be rereading TTL at the moment). And in Mrs Dalloway, it is used in the playful sense - 'what a lark!'

Although it's slow going for me, I am enjoying reading the Middle English. So many fantastic words. 'Saucefleem' for 'pimply'. Hilarious and evocative. I feel a feeling of saucefleem whelkes crawling all over me as I read the word!

I shall now sit down and memorize the first 18 lines of The General Prolouge. Thank you John!